I Corinthians 11:

23 For I received of the Lord that which also I delivered unto you, that the Lord Jesus in the night in which he was betrayed took bread; 24 and when he had given thanks, he brake it, and said, This is my body, which is for you: this do in remembrance of me. 25 In like manner also the cup, after supper, saying, This cup is the new covenant in my blood: this do, as often as ye drink it, in remembrance of me. 26 For as often as ye eat this bread, and drink the cup, ye proclaim the Lord’s death till he come.

On the other occasion when Paul explicitly states that he “received” a tradition, he is also explicit about the source: “I received from the Lord what I also handed on to you” (1 Cor 11:23). The tradition is about the words of Jesus at the last supper (vv. 23-25) . . . . Paul certainly does not mean that he received this tradition by immediate revelation from the exalted Lord. He must have known it as a unit of Jesus tradition, perhaps already part of a passion narrative; it is the only such unit that Paul ever quotes explicitly and at length. . . . Paul’s version is verbally so close to Luke’s that, since literary dependence in either direction is very unlikely, Paul must be dependent either on a written text or, more likely, an oral text that has been quite closely memorized. . . . Paul cites the Jesus tradition, not a liturgical text, and so he provides perhaps our earliest evidence of narratives about Jesus transmitted in a way that involved, while not wholly verbatim reproduction, certainly a considerable degree of precise memorization.

. . . .

[Paul’s] introduction to the tradition about the Lord’s Supper in 11:23 (“I received from the Lord”) focuses on the source of the sayings of Jesus, which are the point of the narrative, and claims that they truly derive from Jesus. He therefore envisages a chain of transmission that begins from Jesus himself and passes through intermediaries to Paul himself, who has already passed it on to the Corinthians when he first established their church. The intermediaries are surely, again, the Jerusalem apostles, and this part of the passion traditions will have been part of what Paul learned . . . from Peter during that significant fortnight in Jerusalem. Given Paul’s concern and conviction that his gospel traditions come from the Lord Jesus himself, it is inconceivable that Paul would have relied on less direct means of access to the traditions. . . . the authenticity of the traditions he transmitted in fact depended on their derivation from the Jerusalem apostles. We might note that his claim, as an apostle, to have the same right as the Jerusalem apostles to material support from his converts (1 Cor 9:3-6) is based on a number of reasons, but the final and clinching argument is a saying of the earthly Jesus (9:14).

(Bauckham, pp. 268 f.)

Bruno Bauer’s analysis as set out by Albert Schweitzer:

Bruno Bauer’s analysis as set out by Albert Schweitzer:

The Lord’s supper, considered as an historic scene, is revolting and inconceivable. Jesus can no more have instituted it than he can have uttered the saying ‘Let the dead bury their dead.’ In both cases the offence arises from the fact that a conviction of the community has been cast into the form of a historical saying of Jesus. A man who was present in person, corporeally present, could not entertain the idea of offering others his flesh and blood to eat. To demand from others that while he was actually present they should imagine the bread and wine which they were eating to be his body and blood would have been quite impossible for a real person. It was only later, when Jesus’ actual bodily presence had been removed and the Christian community had existed for some time, that such a conception as is expressed in that formula could have arisen. A point which clearly betrays the later composition of the narrative is that the Lord does not turn to the disciples sitting with him at table and say, ‘This is my blood which will be shed for you,’ but, since the words were invented by the early church, speaks of the ‘many’ for whom he gives himself. The only historical fact is that the Jewish Passover was gradually transformed by the Christian community into a feast which had reference to Jesus.

(Schweitzer, pp. 132 f)

Bauckham, Richard. 2008. Jesus and the Eyewitnesses: The Gospels as Eyewitness Testimony. Grand Rapids, MI: Eerdmans.

Schweitzer, Albert. 2001. The Quest of the Historical Jesus. Edited by John Bowden. Minneapolis, MN: Fortress Press.

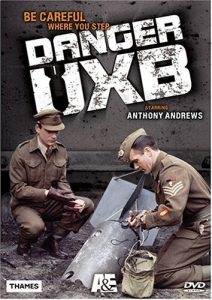

On the other hand, some questions are more pressing. Even not making a decision is still a decision. When I think of life-or-death decisions that demand a choice, I can’t help but recall the series

On the other hand, some questions are more pressing. Even not making a decision is still a decision. When I think of life-or-death decisions that demand a choice, I can’t help but recall the series