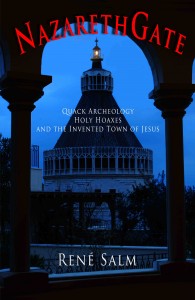

Until some major new finds turn up at new digs I am convinced that there is no archaeological evidence for the existence of Nazareth at the time of Jesus. I have been slowly reading the first six chapters of René Salm’s new book, NazarethGate: Quack Archeology, Holy Hoaxes, and the Invented Town of Jesus, stopping to consult wherever I can his footnotes, his citations of various archaeologists’ works, and at this point I have found his argument to be both

Until some major new finds turn up at new digs I am convinced that there is no archaeological evidence for the existence of Nazareth at the time of Jesus. I have been slowly reading the first six chapters of René Salm’s new book, NazarethGate: Quack Archeology, Holy Hoaxes, and the Invented Town of Jesus, stopping to consult wherever I can his footnotes, his citations of various archaeologists’ works, and at this point I have found his argument to be both

- decisive with respect to the non-existence of Nazareth until well into the latter half of the first century CE

- and absolutely devastating in his analysis of archaeologist Ken Dark’s published efforts to prove the presence of early first century domestic dwellings there.

Many people understandably find the minutiae of archaeological reports and debates to be tedious. They are not light reading, especially for anyone new to a particular study. Sensibly they are willing to defer to the specialists in the field. I am by no means a specialist but I can still read the literature — it is not as complex as advanced mathematics or quantum physics — and follow exchanges of views among archaeologists and readers of their reports. Reasonably intelligent lay readers are able to distinguish between those claims made with the support of clear evidence and others made on the basis of more speculative reconstructions. With some extra effort those same readers can also identify where a scholar has misunderstood or misused the works of others. Nor after a little immersion is it very difficult to detect tell-tale signs of ideological bias. (I elaborated on this point in Can a lay person reasonably evaluate a scholarly argument?)

I would love to see serious engagement with the detailed arguments in Salm’s book. I would love to see how specific questions and data are addressed. Maybe Salm’s conclusions can be overturned after all, or at least modified. We won’t know until we see further reports, discussions and responses.

Unfortunately it appears so far that scholars (and others) who ardently oppose the very idea that Nazareth did not exist at the time of Jesus, and who loathe the mere mention of Salm’s books, are not very different from that handful of scholars (Maurice Casey, Bart Ehrman, James McGrath) who have attempted to publicly refute the writings of Jesus mythicists. Their reviews of Salm’s first book (The Myth of Nazareth) leave the knowledgeable reader with the strong suspicion that they read no more than a few snippets of the book and those with ideological hostility. The main arguments are ignored.

Though I acknowledged that the field of archaeology is complex enough for most people to defer to the specialists, some lay critics of Salm tend to rely upon authorities indiscriminately for the purpose of hectoring and belittling a lay scholar who has genuinely mastered the published literature in this particular niche topic. I would love to see people like Tim O’Neill engage seriously with both Salm’s arguments and his critiques of Dark’s published work.

René Salm’s method

Salm does not attempt to hide his outsider status. His account of how he undertook his study of the archaeology of Nazareth reminded me of some of my own experiences in embarking on serious biblical studies. Both of us found the now defunct online discussion group where scholars and lay persons met, CrossTalk, an informative starting point. Salm writes:

From the start I left no stone unturned, did not hurry, skip any steps, nor overlook even minor reports. Lacking a relevant Ph.D. I knew that thoroughness would be my only credential — one that would have to be earned.

I began with the most accessible secondary material: encyclopedia articles and entries in secondary reference works. Scouring the footnotes and references, I slowly accumulated the obvious primary sources. Among these, the largest was B. Bagatti’s long tome Excavations in Nazareth (vol 1, 1969). . . This book was the first (and often only) resource used by scholars who ventured to write about Nazareth’s archeology. . .

[Salm then describes his heavy use of the University of Oregon library and special help of a librarian who was able to procure for him “obscure books and hard-to-find articles”.] He validated my status as a resident scholar so that the University of Oregon’s critical interlibrary loan facilities would be made available to me as if I were a member of the faculty.

Accumulating the necessary research material also required trips to major libraries in Seattle and San Francisco. . .

Collecting the requisite material was of course only the first step. Each account, description, or excavation report had to be examined in a particularly careful way. It was not good enough simply to read the report, or even to collate all of its itemized artifacts in columns by type, date, and so on — things I learned to do quite early on. Incidentally, such collation could be quite revealing. For example, on one page Bagatti dates a certain pottery shard to the Roman period and on another page to the Iron Age. Such errors are quickly detected through careful and complete bookkeeping.

All this was tedious, but the problem which required the most time, by far, was that each and every claim had to be tested. For example, in one place Bagatti claims that a fragment of pottery is “Hellenistic” — but the parallels he gives, when checked, date to the Iron Age. In another place, his alleged “Hellenistic” parallels actually date to Roman times. Richmond, too, in 1931 claimed that six oil lamps found in a Nazareth tomb were “Hellenistic.” Subsequent redating by specialists . . . shows, however, that all the lamps in question are Roman.

There was also the problem of mislabeling. I learned that one scholar (J. Strange) termed the kokh type of tomb “Herodian” . . . . However, the important work of H.-P. Kuhnen shows that kokh tombs were not hewn in the Galilee before c. 50 CE. (They continued in use to c. 500 CE.) Thus, the term “Herodian” for these tombs is clearly erroneous and very misleading. . . .

In the above and other ways it soon became clear to me that serious flaws characterize the primary reports, not to mention the secondary reference articles based on them. . . .

Though I could read, tabulate, compare, and analyze the reports which came under my gaze, I could not venture any opinion myself, for I am certainly not a professional archeologist nor have I excavated in Nazareth. As a result, any opinion which I produced that disagreed with Bagatti, Strange, Richmond, etc., was necessarily the verifiable opinion of a leading specialist in the relevant field or subfield. This gave my writing ‘teeth,’ but it also required an enormous amount of time. In the process I could not help but become somewhat educated in Galilean archeology. That education extended to language classes at the university which afforded me the ability to also read excavation reports in Hebrew. . . . (NazarethGate, pp. 15-17, emphasis added)

Different from the earlier book

Salm’s second book, NazarethGate, is quite different from his first. The new work includes chapters that are (sometimes) edited versions of articles written and published since the first book. Some of these chapters are largely polemical (anti-Christian or anti-religion) in tone and written for militant atheist publications. The significance of the absence of Nazareth for the Jesus mythicist debate reverberates through a number of these chapters. If Nazareth did not exist, then clearly “Jesus of Nazareth” could not have existed either. I must point out that there is more nuance in the discussion than that: Salm is well aware of the arguments that some other “Jesus” figure lies behind the gospels and he is also very cognizant of the debates over the original derivation of “Nazareth” as an epithet or its cognates as the name of a sect, including the possibility of pre-Christian origins.

Frank Zindler writes the Foreword. He lists nineteen reasons to think that Nazareth did not exist in the early half of the first century, many of them having been extant prior to archaeological digs. This section nicely segues into Salm’s opening chapter (the Introduction) in which he adds further such reasons and addresses some of the complexities involved in understanding the meaning of “of Nazareth” and “the Nazarenes” etc in the Gospels.

What I was most keen to read in the new book were Salm’s responses to Ken Dark’s views. Continue reading “NazarethGate”