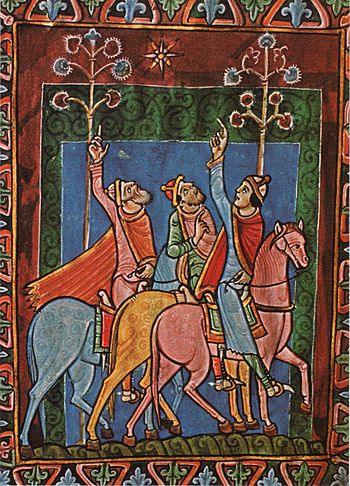

Whenever I hear the word “myrrh,” I can’t help but remember a comedy bit by Cathy Ladman (note: you may not be able to view that video in your region; if so, see http://jokes.cc.com/funny-god/9xm00l/cathy-ladman–gold–frankincense-and-myrrh). She tells us:

My best friend is Lutheran and she told me when Jesus was born, the Three Wise Men visited him and they brought as gifts: gold, frankincense and myrrh. Myrrh? To a baby shower?

So in my head, “myrrh” is always pronounced with a New York/Brooklyn accent.

But seriously, why did those mysterious men from the East bring those three particular gifts to Bethlehem?

Gifts fit for a king of kings

In general, modern scholars have explained Matthew’s choice of the three gifts as simply items fit for a VIP. We shouldn’t worry too much, they argue, over their specificity. For example, in his commentary on Matthew, John Nolland says:

No particular symbolism should be attributed to the individual items making up the present from the Magi: as expensive luxury items the gifts befit the dignity of the role for which this child is born. An allusion to Is. 60:6 is possible: Israel being glorified in the person of the messiah by the wealth of the nations. (Nolland, 2005, p. 117)

According to this view, Matthew intended no deeper meaning. And yet we still have that nagging suspicion that something more is going on here. After all, as Nolland himself notes more than a thousand pages later, Mark wrote that Jesus, while hanging on the cross, had refused wine mixed with myrrh. But Matthew changes the story so that the wine contains gall instead of myrrh, and rather than simply refusing it, Jesus tastes the mixture before turning it down. Did Matthew consciously move the myrrh from Jesus’ death scene to his nativity?

Myrrh oil for anointing

Margaret Barker, in Christmas, The Original Story, reminds us that myrrh was originally a vital component in the oil of the temple, however: Continue reading “Why Did Matthew’s Nativity Story Have References to Gold, Frankincense, and Myrrh?”

Philo was a Jewish philosopher in Egypt who died around 50 ce. Much of his literary work was an attempt to explain Jewish beliefs in the language of Greek (or Hellenistic) philosophers.

Philo was a Jewish philosopher in Egypt who died around 50 ce. Much of his literary work was an attempt to explain Jewish beliefs in the language of Greek (or Hellenistic) philosophers.