A muddle of mavens

For several months now, I’ve been poring over works written by a contingent of New Testament scholars who I like to call the Memory Mavens. This group claims that “memory theory” offers new perspectives on Jesus traditions and provides new insights on how those traditions eventually found their way into the written gospels. Some of the best-known authors in this subfield include Alan Kirk, Tom Thatcher, Anthony Le Donne, and Chris Keith. In this introduction we’ll examine some of the basic ideas in memory theory, while attempting to nail down some definitions and core concepts.

Unfortunately, the often imprecise and confusing language in use under the umbrella of “memory,” tends to impede our understanding. Much of the ambiguity in terminology stems from the broad range of meanings that encompass the English word “memory,” which can refer to a personal recollection, the human faculty or ability to remember, a commemorated event, or a given period of time in which things are remembered. But the addition of psychological and sociological layers aggravates the problem, especially when people simply use the word “memory” without clear context or antecedent.

If you search for works on memory, you will find countless examples of self-help books whose authors promise to improve your recollection of names, numbers, events, and anything else you want to remember. On a somber note, you will also find many books discussing Alzheimer’s and other forms of dementia. Generally speaking, when most people hear the term “memory theory,” they think of the faculty of (individual) human memory or the physiological and psychological aspects of personal recollection.

The constructed past

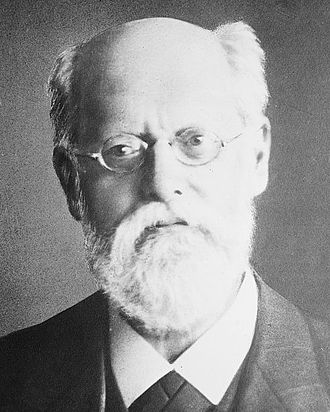

However, when the Memory Mavens talk about “memory,” they usually mean collective memory. In the 1920s, sociologist Maurice Halbwachs observed that we do not remember the past independently, but within groups, and that we understand and interpret all memories, even those we experience directly, within social frameworks. Hence, we have no access to the direct past; we see only the interpretation of the past as it is shaped by present circumstances.

Halbwachs’ theory of collective memory may at first seem paradoxical. It changes our focus from the past to the present, while it diminishes the role of the individual in favor of the group. The past, then, is not so much retrieved from our personal recollections, but rather constructed in the present by means of our current social frameworks.

[T]he collective frameworks of memory are not constructed after the fact by the combination of individual recollections; nor are they empty forms where recollections coming from elsewhere would insert themselves. Collective frameworks are, to the contrary, precisely the instruments used by the collective memory to reconstruct an image of the past which is in accord, in each epoch, with the predominant thoughts of the society. (Halbwachs, 1992, p. 40)

Taken to the extreme, collective memory theory erases the past, replacing it with the present, and equates tradition history with fiction, leaving us nothing but mere constructed stories. As a result we see scholars periodically chastising “presentist,” “constructivist” sociologists for being too skeptical. For example, Jan Vansina wrote:

Continue reading “The Memory Mavens, Part 1: A Brief Introduction to Memory Theory”