This post continues on from The Secular Approach to Christian Origins, #3 (Bias) and addresses the next stage of Professor James Crossley’s discussion on what he believes is necessary to move Christian origins studies out from the domination of religious bias and into the light of secular approaches.

This post continues on from The Secular Approach to Christian Origins, #3 (Bias) and addresses the next stage of Professor James Crossley’s discussion on what he believes is necessary to move Christian origins studies out from the domination of religious bias and into the light of secular approaches.

In the previous post we covered Crossley’s dismay that scholarly conferences in this day and age would open with prayer, look for ecumenical harmonizations through all the differences of opinions and tolerate warnings against straying from the basic calling to feed Christ’s flock with spiritual nourishment. Theologians can even seriously publish arguments that would never be found in other fields of history as we see with N.T. Wright’s arguments for the historicity of the bodily resurrection and the widespread acclaim that his scholarship has attracted among his peers.

Crossley argues that the solution to Faith’s domination of Christian origin studies is for more practitioners to take up a solid secular approach. There should be more scholars in Theology or Religion departments doing history the way other historians do. Or more specifically, they should take up social-scientific methods of history.

In fact, however, the social scientific approach to historical inquiry is only one of many types of historical studies open to other historians but Crossley does not address these alternatives in this book. Crossley is concerned with applying only models of economic and social explanations for the rise of Christianity. He wants to avoid the common current approaches that explain Christian origins as the accomplishments of a unique man or the inevitable victory of a superior belief system.

Having addressed the way Christian bias (or more politely, partisanship) has produced “unnatural” historical explanations for Christianity Crossley turns to two examples of how “partisanship” has actually worked to produce positive results and taken historical studies a step closer towards a more “human” or “natural” account.

A Tale of Two Scholars

Two biographies are his primary exhibits.

What I will do here is show how details and biases of a given scholar’s life can affect the discipline — in other words, how partisanship can work in practice. . . . I think the [biographical] details are important because they provide crucial insights into the ways in which the discipline has been shaped and can be shaped. I also feel a bit naked without them. (p. 27)

Some of us might recall Crossley’s doctoral thesis supervisor, Maurice Casey, having a penchant for judging others through details of their past lives. As I pointed out in Casey’s Instruments of Demonization the professor would call up details from the difficult childhood or any past negative religious association or even the nationality of one who had crossed him with a bad review or whom he simply chose to demonize. Crossley has even expressed gratitude (in Jesus in an Age of Neoliberalism) for Casey’s “biographical analyses” of “mythicists” and rebuffed personal attempts to advise him of their gross, sometimes slanderous, inaccuracies.

So I have learned to be wary of Crossley’s claims to be able to explain a person’s views and efforts in terms of their personal biography, especially of his apparent need to look for such explanations (“I feel a bit naked without them”).

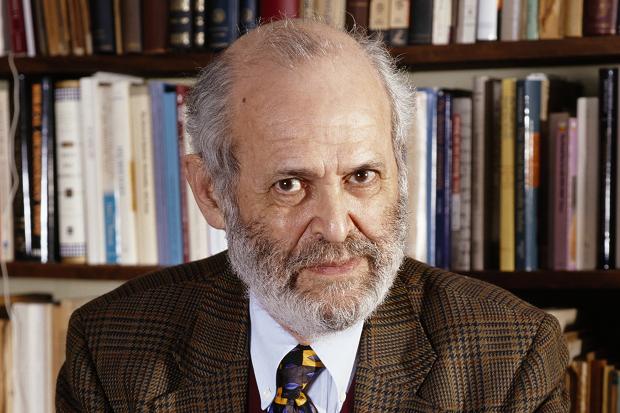

Geza Vermes

One of the most important contributions to Christian origins from a Jewish perspective is Geza Vermes.

Crossley outlines the biographical details:

- born into a Hungarian Jewish family

- christened into Catholicism in 1931

- though his family never forgot its Jewish heritage

- educated as a Catholic

- spent time in Louvain and paris with the Father of Notre-Dame de Sion

- developed interest in Hebrew Bible and postbiblical Judaism

- special interest in Dead Sea Scrolls

- some concern for Jewish-Christian relations

- commitment to Catholicism waned

- became more immersed in Jewish society

- by 1969 formally identifying himself as Jewish

- 1970 joined the Liberal Jewish Synagogue of London

- “stands in a Jewish tradition wishing to reclaim Jesus the Jew, ‘distorted by Christian and Jewish myth alike’ but who was ‘in fact neither the Christ of the Church, nor the apostate and bogey man of Jewish popular tradition.'”

But Crossley has saved the best for last:

Another crucial aspect of Vermes’s ideology and one which is difficult to separate from his Jewish interests must be emphasized, namely, his desire to be a thoroughgoing historian. (p. 28)

Crossley assumes readers will understand how a particular ethnic trait or interest is inseparable from “a desire to be a thoroughgoing historian”.

Vermes is thus presented as one who is has a natural kinship relationship with both Christianity and Judaism. And this “partisanship” has enabled him to produce a Jesus who is just the sort of Jesus Crossley wants: one who does not stand out as an anomaly but fits seamlessly into the sort of typical (albeit charismatic) person we would expect given what we can picture from the later rabbinic testimony and the bare bones of the gospel accounts (stripped of all the miraculous and hoo haa elements).

So Jesus’ teaching conformed to what we find elsewhere in Jewish sources. Everything Jesus said has its “typically Jewish” explanation. Crossley sees Vermes’s Jesus as a “rounded portrait of a historically particular charismatic Jewish Jesus”. Vermes’s success lies in avoiding both demonizing Jesus and imagining him as a second Hillel.

By establishing such a “rounded portrait” of Jesus Vermes has given Crossley the Jesus he needs to justify his social-scientific explanation for Christianity’s emergence. Such a Jesus cannot be used by the religiously biased Christian theologians to write the kind of history that primarily seeks to further their confessional interests.

But how valid is this Jesus? Does he not illustrate the very problem Albert Schweitzer said was the bane of all historical Jesus research? Is not Vermes, like so many others before him, discovering a Jesus in his own image?

When Crossley finds virtue in partisanship when it leads Vermes to discover the “true” Jesus is he not falling into the very same trap that became the byword of the “first quest” for the historical Jesus? A Jesus in each scholar’s image?

How can we be sure that this particular Jesus is the “true” one?

Crossley is confident. The thesis has “stood the test of time”:

Indeed, some of Vermes’s distinctive contributions have been extremely influential and so far stood the test of time. In addition to the general view of Jesus the Jew, placing Jesus in the same category of charismatic Jewish holy men such as Hanina ben Dosa has proven to be particularly popular and the overall thesis has not been refuted, even if various details have been challenged. (p. 29)

The question that inevitably follows is this: What value does “the test of time” have among scholars whom Crossley has so thoroughly censured for religious bias?

Is Vermes’s Jesus really so neutral? Recall that his partisanship is not only towards “Jewishness” but also to Roman Catholicism.

See what Vermes has to say about his personal quest for “the historical Jesus”:

It should be emphasized that the present historical investigation of the Gospels is motivated by no sentiment of critical destructiveness. On the contrary, it is prompted by a single-minded and devout search for fact and reality and undertaken out of feeling for the tragedy of Jesus of Nazareth. If, after working his way through the book, the reader recognizes that the man, so distorted by Christian and Jewish myth alike, was in fact neither the Christ of the Church, nor the apostate and bogey-man of Jewish popular tradition, some small beginning may have been made in the repayment to him of a debt long overdue. (p. 17, my bolding)

That sounds to me as though Vermes is identifying himself somewhat with the similarly ambivalent — Christian yet Jewish — Jesus figure. He begins with a feeling for “the tragedy of Jesus”. His Jesus turns out to be a good Jew who always conforms to the Jewish laws; he is also the Jesus who finds no secure place among “his own” but suffers unjustly.

When it comes to the “problem” of the empty tomb Vermes’s historical analysis would be enough to make N.T. Wright (the scholar who dismays Crossley with his arguments for the bodily resurrection):

But in the end, when every argument has been considered and weighed, the only conclusion acceptable to the historian must be that the opinions of the orthodox, the liberal sympathizer and the critical agnostic alike — and even perhaps the disciples themselves — are simply interpretations of the one disconcerting fact: namely that the women who set out to pay their last respects to Jesus found to their consternation, not a body, but an empty tomb. (p. 41)

That paragraph is not history but mystery. And a theological mystery at that.

Vermes reads right through the gospels as if they are windows into historical realities sustained in memories by oral traditions. Never for a moment does he stop and question whether the gospel narrative might in fact be nothing more than literary re-writes of popular Old Testament characters, events and sayings. He assumes they are biographies composed by authors who are drawing upon oral traditions and intending to pass on the historical record, embellished though it might be with miracles and christological messages. So when he sees the account of Jesus and John the Baptist he assumes that the two persons really met and never considers the possibility that the gospel accounts are nothing more than midrashic expansions on Malachi and other OT characters. Not even the fact that the gospels phrases are all allusions to OT sayings and images or that the entire point of the meeting is to introduce theological themes alerts him to the possibility that the story has a literary-theological origin.

Similarly when he comes to the gospel account of Jesus being accused of insanity and rejected by his family. Never for a moment does Vermes read the gospels as recycling the stories of the OT “men of God” who were all rejected by their own; the stories must be true because they would be too embarrassing to make up! Vermes concurs with the gospel narrative that the reason Jesus was hated by the religious establishment was because he knew the Law better than the powers-that-be and was willing to forego the man-made additions to the biblical commands.

I cannot see Vermes as a “serious historian” given his uncritical assumptions about the nature of his source material.

I can understand theologians loving his work because it’s always good for Christians to have a Jew or Jewish perspective provide credence to the foundations of their faith.

And I can understand Crossley’s embracing of Vermes’s “rounded portrait” of Jesus because he is just the Jesus he needs to displace the nineteenth century Romantic “Great Man” view of history with his social-scientific approach. That is, he is a Jesus who can only be described in terms of the typical social and religious generalities we extract from rabbinic writings.

That is, Jesus is not a person: he is a figure representing the social-religious model upon which we wish to build our search for Christian origins.

We will see in the next post how far Crossley goes to depersonalize this Jesus while personifying the gospel sayings to conform to his social-scientific model.

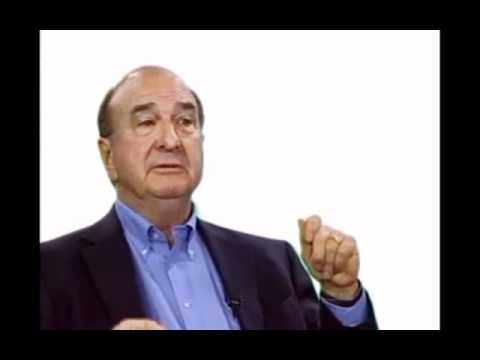

E. P. Sanders

Crossley’s second case-study of how a personal life-story can lead one into the right direction for the study of Christian origins is E. P. Sanders. Actually the only biographical data Crossley has for Sanders is his life-long personal interest in history and religion. Sanders’ “academic autobiography” is available online: Comparing Judaism and Christianity: An Academic Autobiography.

Sanders wanted from the outset to study ancient history and specialize in religion, meaning religion must be studied as from the perspective of history and not theology. (Another central focus of Sanders was his belief that one can only understand a religion through comparing it with another: it is therefore essential that New Testament scholars study Judaism alongside Christianity.)

In order to compare (and therefore understand) religions historically Sanders saw the need to focus on nontheological details such as pious practices (e.g. prayers, sacrifices).

Consequently Sanders has been a pioneer of understanding the historical context of Christian origins. Too many New Testament scholars, Sanders has lamented, know too little about ancient history and sources outside the Bible.

Sanders’ faults many NT scholars for their limited awareness of the ancient world beyond the Bible is certainly a theme I have noticed and have posted on here from time to time. Those NT scholars who do stretch their horizons and seriously compare the biblical literature with contemporary Greco-Roman literature have had (to my mind) astonishingly little impact on the works of other scholars who think of themselves as historians of Christian origins. The fundamental error that Vermes fell into and that I mentioned above is really the standard approach among NT historians. (I have referred a few times now back to my post addressing the insights of Jack Miles and Clarke Owens.)

Even Sanders fell into the same fundamental error of method as Vermes did. Yes it was admirable that Sanders stretched his horizons beyond Christianity to take in another ancient religion that was related to Christianity, but the historian first needs to appreciate the true nature and provenance of his or her sources. Sanders failed to seriously address the question of whether he was confusing the gospels with windows through which to see the past or whether they were stained-glass windows to be studied, analysed and explained at another level.

What happens when the historian does not grasp and address this first step is demonstrated in another post on this blog, Why the Temple Act of Jesus Is Almost Certainly Not Historical. Sanders’ entire explanation for the death of Jesus rests upon the historicity of the gospel account of Jesus casting out the money changers. Without that event being historical he has no explanation for why anyone would have wanted to see Jesus dead and therefore his entire picture of “the historical Jesus” collapses.

Sanders was on the right track. He knew the importance of studying more widely than the Bible. Unfortunately he did not cast his sights widely enough to include the way ancient authors composed their works. That study would have to wait for the likes of Dennis MacDonald and Thomas L Brodie and others. (Admittedly this is a hard call for many NT scholars. To take on board these studies and to fully grasp their implications must inevitably lead to uncomfortable questions about the historicity of the treasured events in the Gospels. Some scholars have reacted with such hostility towards these studies that they have rejected the original meaning and use of the term “parallelomania” as published by Samuel Sandmel and unwittingly broadened its definition to effectively cover the entire field of comparative literature.)

.

Gosh I’m a procrastinator. I fully intended to finish addressing Crossley’s point about bias and social-scientific historical approaches to the study of Christian origins this time. But already I’m at 2463 words! Will have to finish this off next time.

So I’ll sum up the point so far: Crossley sees in Vermes and Sanders commendable pioneers for writing like “historians” rather than “theologians” about Christian origins. But we have also seen some critical failures in the methods of both Vermes and Sanders as historians. We are yet to see the way Crossley’s “social-scientific” history conjures up ideology and theology disguised as something quite different.

Neil Godfrey

Latest posts by Neil Godfrey (see all)

- Questioning the Hellenistic Date for the Hebrew Bible: Circular Argument - 2024-04-25 09:18:40 GMT+0000

- Origin of the Cyrus-Messiah Myth - 2024-04-24 09:32:42 GMT+0000

- No Evidence Cyrus allowed the Jews to Return - 2024-04-22 03:59:17 GMT+0000

If you enjoyed this post, please consider donating to Vridar. Thanks!

This brings back memories. Five or so years ago I was doing an MA where I was looking into how various scholars approached the historical Jesus, and two of the scholars were Vermes and Sanders. Sadly I couldn’t complete it due to the combination of ill health and disagreements with my tutor as to what was “mainstream” scholarship and what was “fringe.” At the time, like Crossley, I thought Vermes and Sanders were both sober-minded critical historians who weren’t fundamentalist axe grinders. Now I can see the very real problems with their methodology and how unquestioned their presumptions were. The thing is, if I – an interested layperson with nothing to show for it except many hours of personal study in the subject – can see this, why can’t mainstream non-fundamentalist scholars?

It’s ironic that in his proud display of the strength of partisanship he should demonstrate its greatest weakness: it’s easy for one to get so caught up in their own ego and personal battles that they lose sight of what they should be doing. “I also feel a bit naked without them (biographical details)” really does say a lot about his interests, as well as his mission to rescue Jesus from the enemy. One has to question just how different his secular approach is if it employs the same apologetics as the faithful (e.g., no one would have ever made it up, it stood the test of time, the empty tomb is an undeniable fact).

@ Daryl– That’s the really astonishing thing isn’t it, that mere interested laypersons can see this so clearly. And it’s not as if we are ignorantly resisting scholarship: all we are doing is drawing a very logical conclusion from what a good number of respected scholars themselves say about the gospels. Then every once in a while a scholar says something that reassures us. Avalos, Brodie, Goulder, Crossley — they all complain about the religious bias that shuts down any easy willingness to consider a truly radical proposal.

@ Greg– A bizarre irony with Crossley’s work is the way he stresses his interest in people as distinct from any quest for the person of Jesus. But his social-scientific approach actually hides “people” behind the abstractions of systems and classes and theory. Of course the nature of the evidence doesn’t allow him to do much else, but then that brings us back to failure to see the evidence for the people who penned the raw evidence he is working with.

“nor the apostate and bogey-man of Jewish popular tradition”—really? I thought the Jews in general are not particularly concerned about “Jesus” historical or otherwise….?….and if they have any views at all—its mostly as a failed messiah or a wise/rebel Rabbi?……….

If “Jesus” is understood as a symbol (rather than a historical person) than it would be right (and interesting) that his image is diverse. “Jesus” would be the canvas upon which a person or groups theological/social/cultural..etc…perspectives would be projected upon and this would be “right/true” because, being subjective…it isn’t “wrong”.

Anyone have an opinion on Abraham Geiger and his Jewish Jesus?

“it’s always good for Christians to have a Jew or Jewish perspective provide credence to the foundations of their faith.”—As a non-Christian I have difficulty in grasping this love-hate relationship Christianity seems to have with Judaism. Is it possible that this tension with Judaism creates biases that could effect a scholar or historians approach and understanding of Judaism?

IMO, The problem with “Jesus” (and Christian origins) is that he IS God/son of God—so, the human/historical Jesus is only half the equation—the other half IS theology—there is no escaping it. Other theologies put God outside of history but Christianity puts God INTO history (in time and place) and if one is to study Christian origins—-I think this aspect has to be taken into account—the symbolism of Jesus as theology should not be discounted……

So, even if one were to assume that the gospels are recycled midrash or Judaism reinterpreted there is a theological break between the Shema and the Trinity…….perhaps the differences between Jewish theology and Christian theology may provide as much insight into Christian origins as the similarities….?….