PZ Myers has responded to some points by Tim O’Neill about the question of the historicity of Jesus and historical methods — Uh-oh. I get the Tim O’Neill treatment — and I cannot help but adding my own sideline remarks here. Perhaps it’s because I have only just a few hours ago completed a fascinating book by a French scholar that I did not know when I started reading would come to the conclusion that Christianity did not begin with a historical Jesus. But most interestingly his argument for Christian origins was commended as worthy of study by none other than Jacob Neusner. (I will be posting about his work soon.) I have not read Tim O’Neil’s post, only PZ’s, so it’s only a few points raised by the latter that I cover here.

PZ Myers has responded to some points by Tim O’Neill about the question of the historicity of Jesus and historical methods — Uh-oh. I get the Tim O’Neill treatment — and I cannot help but adding my own sideline remarks here. Perhaps it’s because I have only just a few hours ago completed a fascinating book by a French scholar that I did not know when I started reading would come to the conclusion that Christianity did not begin with a historical Jesus. But most interestingly his argument for Christian origins was commended as worthy of study by none other than Jacob Neusner. (I will be posting about his work soon.) I have not read Tim O’Neil’s post, only PZ’s, so it’s only a few points raised by the latter that I cover here.

PZ quotes and discusses the following passage from Tim’s post:

The problem is that the whole of Mythicism, in all of its forms, is based on a fundamental supposition – that a non-historical Jesus form of early Christianity existed – which has no sound evidential foundation. And Occam’s Razor makes short work of this kind of idea.

This is how the Principle of Parsimony applies to the question. It is not merely that, as Myers seems to think, the idea of a single person as the point of origin is “simple” therefore it is most likely. It is that the sources all say that there was a historical preacher as the point of origin of the sect and all of the alternative explanations for how this could be is based on a weak foundational supposition which can, in turn, only be sustained by contorted readings of the texts which are also propped up by still more suppositions.

On the first paragraph, I am not sure that it is correct to charge that “mythicism, in all of its forms, is based on a fundamental supposition — that a non-historical Jesus form of early Christianity existed.” Several mythicists authors I have cited certainly came to that conclusion through an analysis of the evidence but I don’t know which mythicist authors Tim has in mind whom he believes “base their supposition” on the existence of a form of early Christianity that lacked an idea of a historical Jesus.

The second paragraph, however, is indeed problematic and points to some confusion about the nature of many mythicist arguments and methods.

No, it is simply not the case that “the sources all say that there was a historical preacher as the point of origin”. I don’t know that any critical scholar (I am not speaking of apologists) who would say that the four canonical gospels depict a historical preacher. My understanding from reading a good many of them is that they concur that the Jesus of the gospels is a mythical or theological construct. He is certainly not a historical figure. Indeed, they argue that they must look behind the gospels and into inferences about the sources of the gospels to try to find a historical figure who acted more in accord with our understanding of how the world works.

Even most of the letters of Paul posit a Jesus and crucifixion as theological (not historical) constructs. Paul never attempts to “prove historically” that Jesus existed or was crucified. There is a passage (said to be partly inauthentic by some researchers) where he attempts to prove the resurrection by naming persons the readers are supposed to recognize as eyewitnesses. But only apologists would take his testimony as serious historical evidence for the resurrection. Others have argued that there is some kernel of truth behind Paul’s claims about the witnesses to the resurrection in that disciples had visions or became inwardly convicted, etc. But you see the problem for the historian here — we are moving away from the evidence and changing it to say something it doesn’t actually say so that it fits our preconceived model of Christian origins.

So we are reminded of a point that several ancient historians have made when addressing sound methods and that I narrowed down to just one quotation in a post a few months ago. Philosopher of history Aviezer Tucker was addressing the question of whether or not something (in this case a miracle) in the gospels really happened. He explains:

But this is not the kind of question biblical critics and historians ask. They ask, “What is the best explanation of this set of documents that tells of a miracle of a certain kind?” The center of research is the explanation of the evidence, not whether or not a literal interpretation of the evidence corresponds with what took place.

Tucker, p. 99

And that hits the nail squarely on the head.

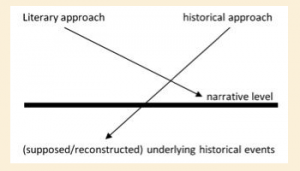

Tim O’Neill appears to be repeating the argument for the conventional wisdom among biblical scholars that is based on a naive reading of the sources: that we should assume they are just as they appear — “biographies”, however exaggerated, of a historical figure. But Tucker is saying that this approach begs the questions. The historian’s first task is to understand why the gospel narratives were written. It is a mistake to simply assume that though they are about a mythical or theological figure and persons who behave most unlike real persons we know from history (even Pilate is depicted as very unlike his portrayal elsewhere) they must nonetheless have originated in history and transmitted through oral retellings until set down by the evangelists. To make that assumption is to sweep aside much scholarship that has indeed suggested other sources for many of the narratives in those gospels, and to sweep aside critical scholarship that has indeed questioned the biographical nature of the gospels. (And there remains the question of how ancient biographies worked anyway since not all of them, despite appearances, are really about historical figures.)

One prominent Old Testament and Dead Sea Scrolls scholar, Philip R. Davies, who was a pioneer of what became known derogatorily as “minimalism” in Old Testament studies — a movement that has continued to gain momentum since the 1990s and many of whose views are now mainstream — wrote the following in one of his last publications:

I … have often thought how a ‘minimalist’ approach might transfer to the New Testament, and in particular the ‘historical Jesus’, who keeps appearing to New Testament scholars in different guises. . . .

I don’t think, however, that in another 20 years there will be a consensus that Jesus did not exist, or even possibly didn’t exist, but a recognition that his existence is not entirely certain would nudge Jesus scholarship towards academic respectability.

The ‘minimalist’ approach he was referring to is nothing other than the way ancient historians (at least the scholarly reputable ones such as Moses I. Finley) work with evidence in fields other than biblical studies. I outlined his starting assumptions and questions on a webpage, In Search of Ancient Israel. I copied the main points of his discussion about faulty assumptions we bring to our reading of the biblical narratives in a blog post, too. Essentially, Davies and those who approached the history of “biblical Israel” in the same way argued that the biblical narratives must not be assumed to be based on historical events, but that such an assumption needs to be tested against other independent data. Archaeological data is not going to help us settle the question of the historicity of Jesus but one can compare other independent texts. Such a comparison will not exclude a comparison with other Greco-Roman literature in order to gain a deeper appreciation for the nature and potential purposes of the gospels. Some biblical scholars have ventured into such comparisons but some have also done so tendentiously. That’s another question that biblical scholars themselves are debating and that needs another post for a thorough treatment.

Here’s how another scholar put it:

Apart from archeological evidence, the only facts we can attain are the texts. We must therefore reason about the texts that relate facts, not about the facts related by the texts.

(Magne, p. 23)

That’s just another way of saying what Aviezer Tucker said:

But this [did this story happen?] is not the kind of question biblical critics and historians ask. They ask, “What is the best explanation of this set of documents that tells of a miracle of a certain kind?”

And when a scholar sees that the evidence points to the gospels not being more widely known until well into the second century, and that by that time they had been heavily redacted, and that their narratives are clearly influenced by comparable stories in the Jewish Scriptures, and that at key points in their narratives they even appear to be deliberately targeting pre-existing beliefs that their narrative is not grounded in historical memory at all, then that scholar has a challenge ahead.

…

One more point. I have been attempting to get some handle on the nature of religion itself according to current anthropological and related studies. It has been a fascinating study. One point that has stood out for me is that models of how new religions start or how sects break off from mainstream religions to promote their own rituals and identities is just how infrequently such developments can be attributed simply to the appearance of a charismatic stand-alone figure who becomes the object of worship and co-creator of the universe, and how unreliable mythical explanations for the origins of their rituals and practices ever are.

As PZ Myers rightly points out, it means nothing to an atheist whether or not Jesus existed historically. (Unless the atheist is one of those idiots who likes to just pose nonsense criticisms for the sake of mocking alone.) But grappling with the evidence itself and attempting to assess it with clear-eyed and sound methods is a fascinating exploration.

…

Davies, Philip R. 2012. “Did Jesus Exist?” The Bible and Interpretation. August 2012. http://www.bibleinterp.com/opeds/dav368029.shtml.

Davies, Philip R. 1992. In Search of “Ancient Israel.” Sheffield, England: Sheffield Academic Press.

Finley, M. I. 1999. Ancient History: Evidence and Models. ACLS History E-Book Project.

Kosso, Peter. 2001. Knowing the Past: Philosophical Issues of History and Archaeology. Amherst, NY: Humanity Books.

Magne, Jean. 1993. From Christianity to Gnosis and from Gnosis to Christianity: An Itinerary Through the Texts to and from the Tree of Paradise. Atlanta, Ga: Scholars Pr.

Tucker, Aviezer. 2009. Our Knowledge of the Past: A Philosophy of Historiography. Reissue edition. Cambridge University Press.

See also posts archived under Ancient Historians, Ancient History and Greco-Roman Biography

Like this:

Like Loading...

Until recently, I had never heard of the

Until recently, I had never heard of the