While thumbing through Cristiano Grottanelli’s Kings and Prophets: Monarchic Power, Inspired Leadership, and Sacred Text in Biblical Narrative, I remember now why I snatched it up a couple of years ago. For some time now, I’ve been working on a simple thesis that would explain the silence regarding Jesus’ actual teaching in the epistles (of Paul, pseudo-Paul, and others).

The Threefold Office

Simply put, I suggest that the root of the issue arises from the earliest Christians’ conception of the messiah and to which office or offices he belonged. We see for example, in Paul’s discussion of the lineage of David, the concept of a kingly messiah. On the other hand, we see in the book of Hebrews a detailed conception of the messiah as priest.

However, in the earliest texts we see practically no hint of Jesus as prophet. Not until the gospels, written decades later, do we find concrete evidence — the strongest, of course, coming from Jesus himself. First in Mark:

But Jesus said unto them, A prophet is not without honour, but in his own country, and among his own kin, and in his own house. (6:4, KJV)

Copied in Matthew:

And they were offended in him. But Jesus said unto them, A prophet is not without honour, save in his own country, and in his own house. (13:57, KJV)

Edited in Luke:

And he said, Verily I say unto you, No prophet is accepted in his own country. (4:24, KJV)

And referred to in John:

For Jesus himself testified, that a prophet hath no honour in his own country. (4:44, KJV)

These statements are obviously late and apologetic in character. They seek to explain why Jesus’ own family, village and nation rejected him. But they also point to a seismic shift in the conception of Jesus and which category (or categories) he belongs to. The identity of Jesus is bound up in Christians’ conception of him as king, priest, and (lastly) prophet.

These categories, by the way, would be further crystalized by later church writers such as Eusebius (Church History, Book I, 3:8) — Continue reading “Saul’s Folly: The King Can’t Be a Jack of All Trades”

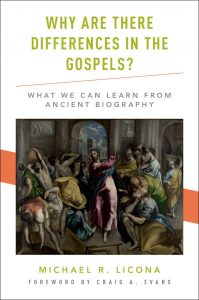

In his recent book,

In his recent book,

[Edit: When first published, this post credited Michael Bird instead of Michael Licona for this book. I can’t explain it, other than a total brain-fart, followed by the injudicious use of mass find-and-replace. My apologies to everyone. –Tim]

[Edit: When first published, this post credited Michael Bird instead of Michael Licona for this book. I can’t explain it, other than a total brain-fart, followed by the injudicious use of mass find-and-replace. My apologies to everyone. –Tim]