Thomas L. Brodie has an epilogue in his latest book, Beyond the Quest for the Historical Jesus, in which he responds to Bart Ehrman’s purported attempt to address the arguments of mythicists, Did Jesus Exist? (I say “purported” because although Ehrman has vehemently denied the charge, he has never, to my knowledge, addressed the actual evidence that he did not himself even read the books by Doherty and Wells that he critiqued. But Brodie is a kinder reviewer than I am.)

Thomas L. Brodie has an epilogue in his latest book, Beyond the Quest for the Historical Jesus, in which he responds to Bart Ehrman’s purported attempt to address the arguments of mythicists, Did Jesus Exist? (I say “purported” because although Ehrman has vehemently denied the charge, he has never, to my knowledge, addressed the actual evidence that he did not himself even read the books by Doherty and Wells that he critiqued. But Brodie is a kinder reviewer than I am.)

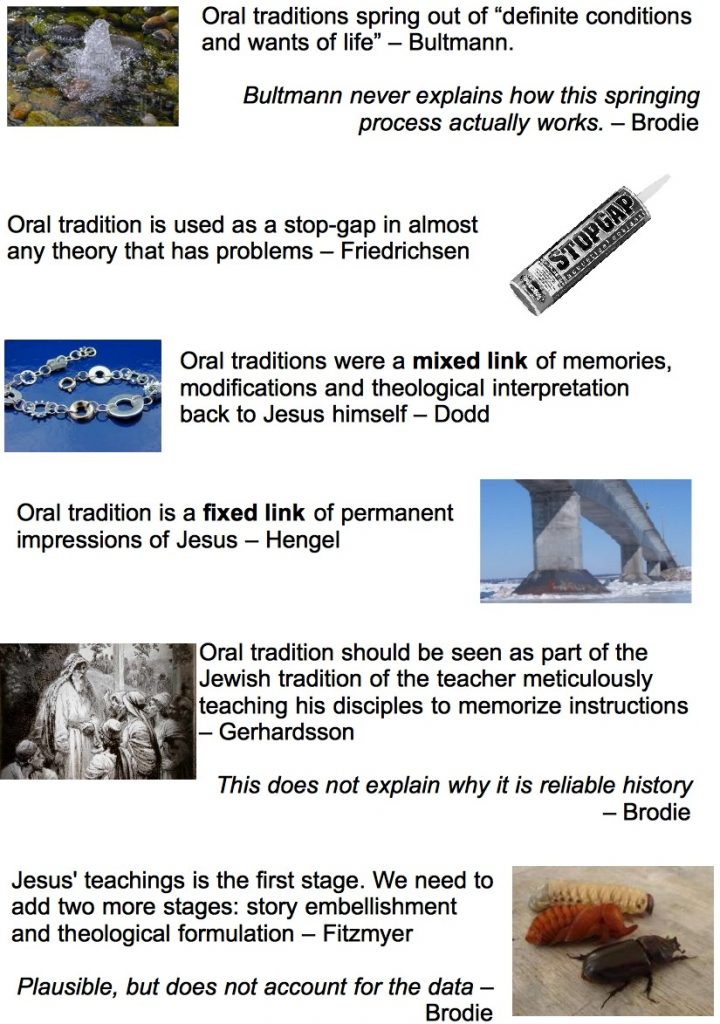

Brodie summarizes the three parts to Ehrman’s book and then responds. A summary of his summaries follows. It dwells mostly on Ehrman’s argument about oral traditions since Brodie (as I have posted recently) is particularly critical of the way biblical scholars “uncritically” rely upon oral tradition to make their reconstructions of Christian origins work.

Part 1: The Evidence for Jesus’ Historical Existence

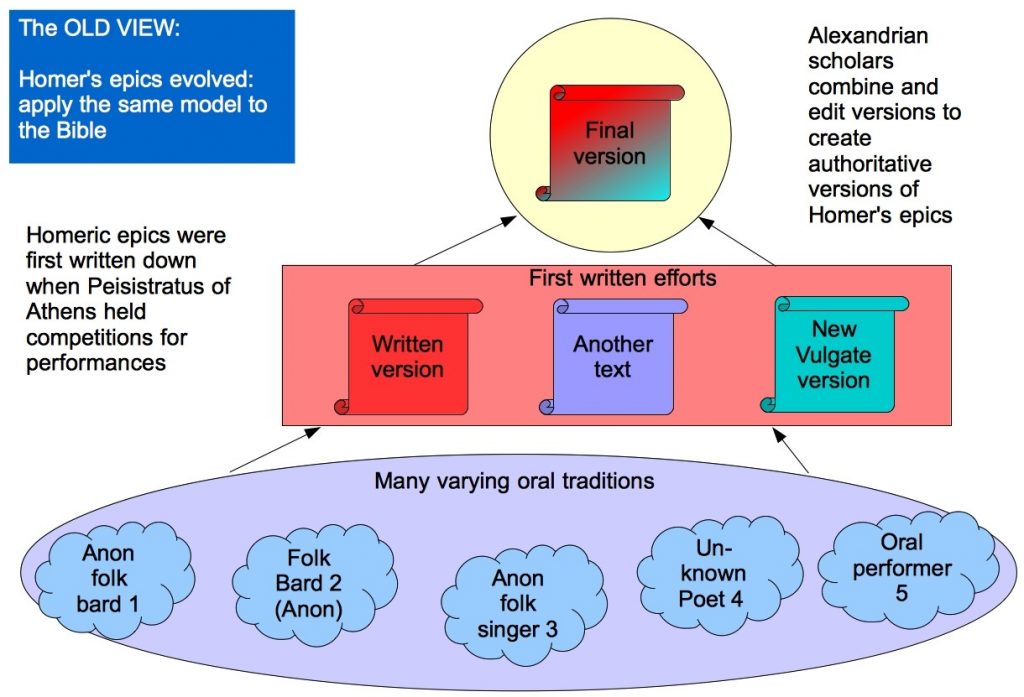

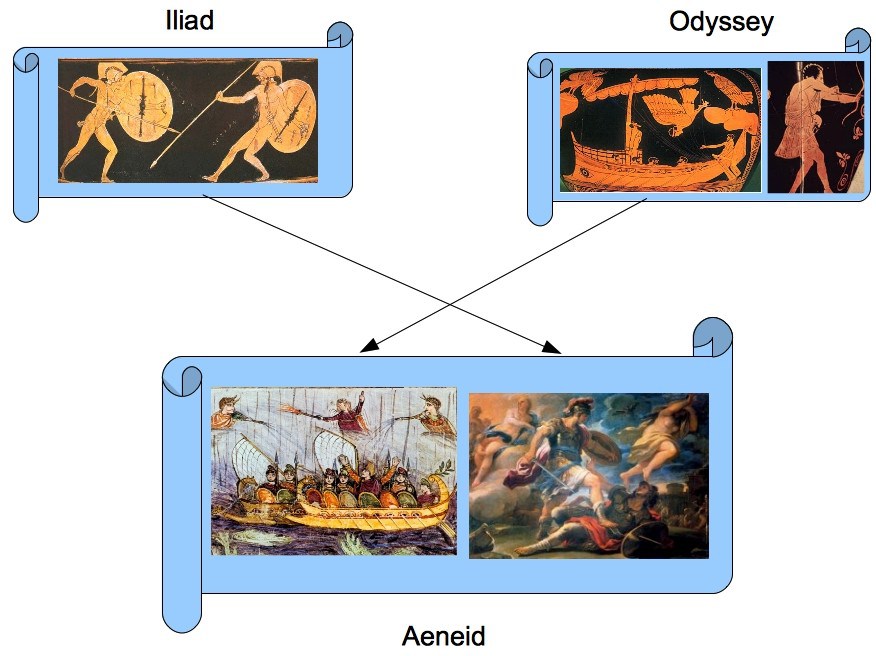

Ehrman’s argument is that all Gospels, canonical and noncanonical, all testify to an historical Jesus, and they are all so varied, each with its own unique material (despite some undoubted borrowing from Mark), that they have to be considered to be relaying to readers independent witnesses of this historical Jesus.

Examination of the Gospels further “indicates that they all used many diverse written sources, sources now lost to us. . . .” — known as Q, M, L, a Signs Source, a Discourse Source, a core version of Thomas, etc. All of these “sources” also speak of Jesus as an historical person. It is also clear that they are independent of one another, so they can all be considered independent witnesses. It is thus inconceivable that they all derive from a single source. They must all ultimately derive from various witnesses to the historical Jesus.

Further, some scholars date Q to the 50s, 20 years after Jesus’ death. And others have “mounted strenuous arguments that” — and one recent study “makes a strong . . . literary . . . argument that” — sources underlying Peter and Thomas date even earlier than 50 CE.

And behind all of these very early (now lost) written sources were oral traditions that dated much earlier. Evidence of oral traditions:

- revised form criticism that assumes oral traditions were the core of written sources

- we have no way of explaining the written sources unless we assume oral tradition was behind them

- Aramaic traces in the Gospels indicates that their sources were originally Aramaic oral sayings

These oral traditions were old. For example, we “know” Paul persecuted the Christians before his conversion. How could he have persecuted Christians if they did not exist? And how could they exist unless they knew orally transmitted reports about Jesus? (Brodie is a kind reviewer. He does not embarrass Ehrman by pointing out the raw logical fallacies in these arguments.)

Brodie notes Ehrman’s insistence upon the importance of oral tradition in the case for Jesus’ historicity:

The role of oral tradition as a basis for all our written sources about Jesus is not something minor; it ‘has significant implications for our quest to determine if Jesus actually lived’ (p. 85 of Did Jesus Exist?, p. 227 of Brodie’s Beyond the Quest)

Other NT sources, the letters of Paul and others, as well as the writings of Ignatius, 1 Clement, Papias — all, according to Ehrman — speak of Jesus as historical and they are all either independent of one another or demonstrably independent of the Gospels, so we can only conclude they acquired their knowledge of Jesus from oral tradition.

Besides — a key point —

the message of a crucified messiah is so countercultural for a Jew that it can only be explained by a historical event, in this case the crucifixion of someone the disciples had thought was the messiah. (p. 227)

Brodie aptly sums up Bart Ehrman’s case:

Overall then, the evidence shows a long line of sources, all independent — all with independent access to the oldest traditions — and all agreeing in diverse ways, that Jesus was historical. Such evidence is decisive. (p. 228) Continue reading “Thomas Brodie’s Review of Bart Ehrman’s Did Jesus Exist?”

Like this:

Like Loading...

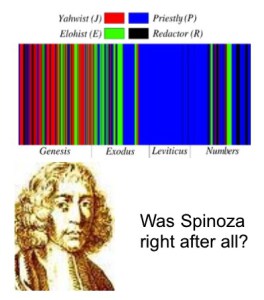

Compare the outcome of criticisms of the Documentary Hypothesis — the thesis that the Old Testament books can be pulled apart into different sources or strata — Priestly, Jahwist, Elohist and Deuteronomist (and a later Redactor).

Compare the outcome of criticisms of the Documentary Hypothesis — the thesis that the Old Testament books can be pulled apart into different sources or strata — Priestly, Jahwist, Elohist and Deuteronomist (and a later Redactor).