The previous posts in this series:

-

-

- 25th August 2020 (introduction and Part 1 and half of Part 2)

- 27th August 2020 (completion of Part 2)

- 28th August 2020 (first half of Part 3)

-

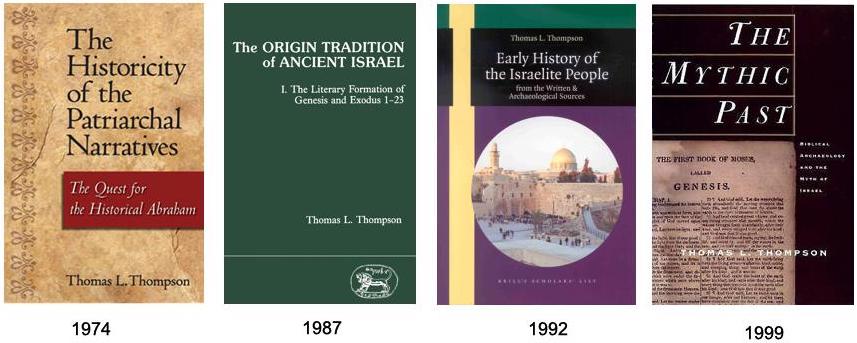

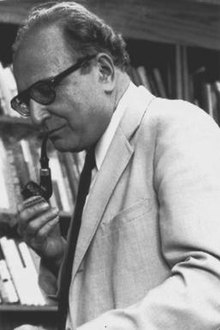

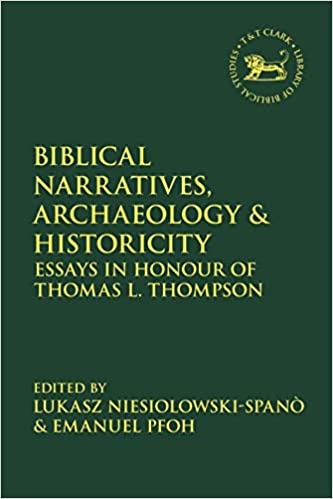

This post concludes my overview of the festschrift to Thomas L. Thompson on his 80th birthday. I hope to post soon a link to a single PDF file of all of these posts. Over the coming months, from time to time, I would further like to cover some of the essays in more detail. The book is expensive and I do appreciate all involved in enabling me to receive a review copy. Hopefully, a less expensive paperback or e-version will be available before long, but till then and for those who are not as financial as they would like to be don’t forget your state and local libraries since most of them will be able to assist you with an interlibrary loan service. So with thanks to those who put this volume together and contributed to it, and to Thomas L. Thompson whose scholarship has been so influential in biblical studies (and of course on me among so many others), here is the final post in my overview discussion of Biblical Narratives, Archaeology and Historicity: Essays in Honour of Thomas L. Thompson.

. . .

Lisbeth Fried’s essay, “Can the Book of Nehemiah Be Used as an Historical Source, and If So, of What?“, builds on Thomas Thompson’s emphasis on “the importance of looking beyond the situation in which the biblical story is set to the situation in which the book may have been written” (p. 210).

Following in that path, we recognize that while the biblical book Ezra-Nehemiah is set in the Persian period, it was written over a long period of time. Much of it is definitely Hellenistic (Fried 2015a: 4-5; Finkelstein 2018); some of it may be Persian, however, and may be used as an historical source if used cautiously and if confirmed by corroborating documents. I test this hypothesis by examining the portrayal of Nehemiah as the Persian governor of Judea during the reign of Artaxerxes I. Is Nehemiah’s portrayal historical, i.e., does his portrayal match what we know in general about provincial governors under Achaemenid rule? (p. 210)

Fried leads readers through a step by step comparison of Nehemiah’s actions with those that Persian inscriptions inform us were typical of the actions and responsibilities of Persian governors: jurisdiction over the temple and its operations, control of temple funds (temples functioned as collection centres for the Persian empire), religious practices of the priests and people, and control over marriages in order to safeguard against the emergence of alliances that might threaten the security of those appointed to administer state power. So though a late composition the book of Nehemiah appears to be consistent practices of Persian governors from Egypt to Asia Minor.

In Ehud Ben Zvi’s “Chronicles’ Reshaping of Memories of Ancestors Populating Genesis” we encounter many instances where the books of Chronicles rewrite events found in Genesis and how we might expect the literati of the day to have been influenced in their perceptions of those events in the more culturally significant book of Genesis.

Reading Chronicles and identifying with the message conveyed by the Chronicler2 led, inter alia, to processes of drawing attention to or away from some events, characters or some of their features, and led to a reshaping and re-signifying of implicit or explicit mnemonic narratives. (p. 225)

Details that on the surface look rather pointless to the lay reader take on fascinating meaning as Zvi takes us through several of those “little details”: Why does Genesis generally speak of “Abraham, Isaac and Jacob” while Chronicles of “Abraham, Isaac and Israel”? Why in Genesis do we follow the adventures of Esau and Jacob while in Chronicles it is Esau and Israel? Do we detect here a subtle attempt to snatch from the Samaritans in the north the identity of Israel for the Judeans in the south? Compare also Abraham’s wife Keturah in Genesis; why in Chronicles is she called a concubine-wife? and why in Genesis do we read that she bore “to Abraham” children but in Chronicles she simply “bore children”? Why are the Genesis and Chronicles narratives about Er so different? Is there significance in the different ways “Adam” is introduced at the beginning of each book? Why does Chronicles find it necessary to merely set out a list of unadorned patriarchal names whereas Genesis introduced some anecdote on the significance of some of those names? Why does the Chronicler think it appropriate to make no mention at all of the Garden of Eden or Flood stories while rewriting other episodes in Genesis? And so on and so on. I found it a most interesting journey of discovery.

The penultimate chapter is by another scholar who has appeared before on Vridar, Philippe Wajdenbaum. Some readers of Vridar will be reminded of Russell Gmirkin’s thesis that Greek authors inspired the books of the Bible when they read Wajdenbaum’s “The Book of Proverbs and Hesiod’s Works and Days“. Debt to Thompson is once again acknowledged in this context:

T. L. Thompson (1992, 1999, 2001) and N. P. Lemche (2001 [1993]) have raised the possibility that the Hebrew Bible was produced in the Hellenistic era. There is no physical evidence for the Hebrew Bible before the Dead Sea Scrolls, and the spread of Hellenism in the Levant after Alexander’s conquest provides the best context for its creation. Thompson’s vision has elicited a paradigm shift in biblical studies, inspiring several scholars to posit a direct influence upon the redaction of several Hebrew Bible books of such Greek classical authors as Homer (Brodie 2001: 447-94; Louden 2011: 324; Kupitz 2014), Herodotus (Nielsen 1997; Wesselius 2002) and Plato (Wajdenbaum 2011; Gmirkin 2017). (p. 248)

Some Hesiod passages:

-

- He does mischief to himself who does mischief to another, and evil planned harms the plotter most.

- The idle man who waits on empty hope, lacking a livelihood, lays to heart mischief-making.

- For a man wins nothing better than a good wife, and, again, nothing worse than a bad one.

There are “similarities of vocabulary between Hesiod and the Septuagint text of Proverbs . . . even though the latter greatly differs from the original Hebrew” so one might well suspect that the translators had been familiar with Hesiod’s Greek poem. Yet Wajdenbaum goes further and argues that “the original Hebrew text itself may have been influenced by Hesiod.” Wajdenbaum lists very many possibilities and acknowledges similar observations other scholars have made concerning Proverbs and Greek moralistic works (including Aesop and Aristotle).

Not only Proverbs but the Song of Songs and Ecclesiastes are also brought into the discussion as well as other Greek poets such as Theognis.

The final essay is “The Villain ‘Samaritan’: The Sāmirī as the Other Moses in Qur’anic Exegesis” by Joshua Sabi — the second chapter taking a look at the Qur’an. Sabi’s discussion is probably the most technical of all in this volume and not the easiest of reads for those not yet initiated into the highly abstract conceptual terminology. It is worth engaging with, however, in order to see a control instance of how a religious text both challenged and rewrote earlier scriptures. Such a case study potentially deepens any discussion of the changes in Jewish-Christian scriptures that most of us are more familiar with. How does one understand the literary creation of a new figure (in this case the Sāmirī) as a rival counterpart to Moses (at the time of the golden calf apostasy) and ancestor of the Samaritans?

Muslim exegetes have been – and still are – obsessed with the historicity of the figure of the Sāmirī. . . .

The novelty in Islamic Qur’anic exegesis is not how these biographical accounts came about, but how the identities are constructed and construed literarily. In the minds of the exegete the ambiguity of theSāmirī figure’s Qur’anic identity left him with no option but to venture into the realm of mythologized understanding of history according to which the Qur’an is both the eternal word of God and his message of salvation to mankind. The invention of such a figure with all the theological elements of iconoclastic theology‘ and literary anatomy of mythology was construed as history. Exegetes had to invent another Moses whose biography is a mimicry of the biblical and Qur’anic Moses. In their trying to solve the ambiguity of the Sāmirī’s story and his culpability, exegetes failed to see the Qur’an’s restorative approach to Scriptures as well as to humans’ fragile relations to God.(pp. 271-72)

Niesiolowski-Spanò, Lukasz, and Emanuel Pfoh, eds. 2020. Biblical Narratives, Archaeology and Historicity: Essays In Honour of Thomas L. Thompson. Library of Hebrew Bible / Old Testament Studies. New York: T&T Clark.

At some point in the not-too-distant future (we hope), you’ll be able to buy a new book, an anthology of papers related to Jesus mythicism. In it, you’ll find essays from the usual suspects, including Neil and me.

At some point in the not-too-distant future (we hope), you’ll be able to buy a new book, an anthology of papers related to Jesus mythicism. In it, you’ll find essays from the usual suspects, including Neil and me.