1. Billionaire Logic and the Death of JFK

2. Billionaire Logic and the Death of JFK / 2 —

3. Billionaire Logic and the Death of JFK / 3 —

4. Billionaire Logic and the Death of JFK / 4 —

5. Billionaire Logic and the Death of JFK / 5 —

6. Billionaire Logic and the Death of JFK / Conclusion and Commentaries

Part 4 of Greg Doudna‘s the interview with John Curington.

The previous installment ended with Curington’s testimony concerning a meeting between H.L. Hunt and Lee Oswald’s wife, Marina. Discussion of that meeting continues here.

Further details covered: circumstances surrounding Oswald’s murder; rowdy crowds at Adlai Stevenson’s visit to Dallas; and retrieval of an autographed book.

~ ~ ~

GD: You mentioned that it was maybe thirty minutes. That’s not a very long time for a visit.

JC: It would be less than—oh he wouldn’t, no, that would be a long time for Mr. Hunt to spend with somebody. I don’t believe he’d have had any interest whatsoever in other than a five or ten minute conversation.

GD: OK.

JC: Again, you’re going back to what most people would do, but you know, he just wasn’t most people.

GD: OK.

JC: But again, when I make a statement like that, or when I write something like that, when Marina Oswald denies the story, most people hearing my remarks wash ’em off as a fictitious story. Nothing I can do about that. You know, they’ve got their opinion. But I know—you just don’t go lock a door between two buildings that’s never been locked before, never been locked since. You don’t normally go in and tell every Hunt employee to go home if in fact they are there. And you don’t stay in the lobby and if a Hunt employee comes in to send them home. It would suggest to me that he wanted somebody coming into that office that he didn’t want anybody else to recognize or see.

GD: Did she speak to you or anything?

JC: No, my instructions were not to look at her, not to speak to her. She didn’t look left, didn’t look right, I didn’t show any recognition whatsoever. She was well dressed, her hair was combed, had on lipstick, she would not be what I would call a pretty woman, but sort of an attractive woman you know, just the way she walked and carried there—she didn’t look left, she didn’t look right, she punched the elevator door. Of course at that time all of the elevators were on the ground floor. I think there were four there in the lobby. It opened immediately, she disappeared, and came back within a less than a thirty minute period of time.

GD: Is the fact that she says she never went to see Mr. Hunt—could that be as simple as he asked her not to tell anyone?

JC: Well, again in fairness to her, she may not have known. But you’ve been around me long enough to know that I sort of have a grasp of the situation—

GD: Yes.

JC: —going around me, you know.

GD: Yes.

JC: I’m not going to be in the lobby under a very set of mysterious instructions, see a lady come in that is on the news 24 hours a day 7 days a week, that I don’t know who she is, you know.

GD: Right.

JC: An orangutang if he had been with me he could have told me who the lady was there.

(This is one of Mr. Curington’s favorite expressions to emphasize something that, in his opinion, should be obvious, some form of even an orangutang could figure that out.)

So I don’t think, you know—I don’t have any reservation, conscience whatsoever in telling that story. That’s exactly what happened, and I think what happened with Marina Oswald, one, Mr. Hunt could or could not have given her a pretty substantial gift. He could or could not have identified himself. Normally he wouldn’t identify himself. But he just had enough ego that in his mind, if he could talk to Marina Oswald for three or four minutes, he could pretty well tell anything she believed as far as Lee Harvey Oswald and Kennedy was concerned.

GD: And when you saw her, how long did it take for you to say, “That’s Marina Oswald”?

JC: The minute she was out of the car. Of course I had an opportunity to observe her for about a two hundred foot walk there, so, you know, it wasn’t just a haphazard glance where well maybe it is, maybe it’s not.

But, anyway, I’m the first to admit, that’s my story, she has a different one, but mine’s correct and hers may not be deliberately incorrect, but she may not have known any differently.

GD: That’s one of these unexplained questions, as to what that meeting was about, but who knows—yeah.

JC: Yo. But anyway, having said that, you know, we could speculate forever on did this happen or did that happen. The comments that I am making leave just as many unanswered questions as when we started. But I can move that pendulum a little bit, a little bit step further.

GD: Let’s go back to Civello there in Dallas. Was Civello under any other Mob boss?

JC: Civello was not a high profile Mafia leader. But he was one of the smarter Mafia leaders, and in a way more cruel. He ran his part of the United States with an iron fist—but in a gentlemanly manner you know. He just had the ability to get things done the way he wanted them done, without a lot of the adverse publicity that some of the people out of Chicago and New York and Los Angeles may have done there.

When the United States was divided there were eight different sections in the United States. It wasn’t an organizational chart, but they didn’t go out of their geographical area. And it was a gentleman’s agreement, this is your area, and you run it. You don’t get involved in this place, and you don’t get involved over here, and we’re not interested in your concerns as to what happens in Louisville Kentucky. You run your business and we’ll take care of the rest of it here.

I would guess that Marcello—well I wouldn’t have any way of guessing—but it wouldn’t be uncommon for Marcello to come to Dallas two or three, four times a year, you know—

GD: Marcello?

(Carlos Marcello was head of the New Orleans crime family from 1947 to the 1980s, considered one of the top Mob bosses in the United States. Marcello’s sphere of operations included Dallas, and according to an FBI informant, Jack Van Laningham, Marcello said, speaking of Dallas, that “all the police were on the take, and as long as he kept the money flowing they let him operate anything in Dallas that he wanted to.”10)

JC: Yeah. It wouldn’t be uncommon, you know, to get a call, “Well, Marcello’s here if you want to drop by.” Nothing planned, nothing formal, nothing regimented or—just a routine thing. Normally it wasn’t a formal meeting. It sort of was like saying, “If you and Mr. Hunt—Marcello’s going to be in town tomorrow, just stop by the liquor store by the airport”—just very informal, no scheduled meeting, no plan to get together, no drawing up a plan or anything—

GD: Most people would be scared to meet these guys.

JC: I had a limited knowledge of a lot of these activities. But astute people don’t have to go into a long-winded detailed explanation of what to do or how to do it. Just three or four words gets the message across you know. And I don’t think Civello, or Marcello, or H. L. Hunt or anybody else is gonna sit down and write out a plan, and discuss it, and call in people to evaluate it—

Again, I’m making a statement. It has nothing to do with anything. But just suppose that H. L. Hunt did have enough concern that Lee Harvey Oswald needed some way not to testify. All he’d have to say is, “Man if there’s any way in the world that somebody could get to Oswald and keep him quiet.” That’s all that would be said, you know. Civello wouldn’t say, “Well what do you want me to do? How much money you gonna—?” Its not that kind of conversation at all. People want there to be something like that, where you want a committee meeting, and you want a faculty meeting, and you want an outlined plan, and you want it written down, and you want to rehearse it and go over it. Its not that kind of a deal at all.

GD: OK.

JC: But the people that think they’re in the know, they believe they have every answer in the world as to why Jack Ruby should not have been at the spot he was when he shot Lee Harvey Oswald. Again, my opinion. I’m not giving you any evidence whatsoever. But in my opinion, Ruby was given instructions to get rid of Lee Harvey Oswald. He didn’t want to do it! But he was afraid not to do it. So he left a paper trail as wide as he could, on protecting his image. And everything he did corresponded with the delay that exactly corresponded with what the Dallas police department was bringing on themselves. Not deliberately. But they had the car parked wrong. That cost ten minutes. They had to do something else to change the deal there. So the Dallas police department was making time mistakes there, so when the shooting <unintelligible>, Ruby over here was leaving the best defense he could as to where he was and it being impossible for him to be there. But by him building up his defense theory, and the Dallas police department making mistakes, put the two together, unintercooperated (sic) by anybody else, to me the explanation is just as simple as two and two is four.

The police department made enough administrative errors that it delayed the meeting about fifteen minutes from the schedule. Jack Ruby didn’t know those things were going on. If the Dallas police department had done what they were supposed to do, and not made the errors that they did make, Oswald would have been in the car and disposed of by the time Jack Ruby was building his alibi that he couldn’t have been there. Everything just unraveled where, without any assistance from anybody, just unraveled, to put him where he was able to confront Lee Harvey Oswald and do just exactly what he did.

Now me saying that doesn’t make it happen that way. You can accept it or reject it. That’s my theory as to what happened there. The Dallas police department didn’t plan on making the mistakes it did. Ruby knew what time that he should have been coming out of that deal. He scheduled everything he did, going to the Western Union office, calling somebody, calling in, so it would have been impossible for him to have been there. I don’t think Ruby wanted to do the shooting. But then he had no other choice. You know, somebody told him what needs to be done. And he knew if he didn’t do it, he could very well have been ground up in a sausage grinder, and all his brothers and sisters and everybody else there.

Now me saying that doesn’t make it happen that way. You can accept it or reject it. That’s my theory as to what happened there. The Dallas police department didn’t plan on making the mistakes it did. Ruby knew what time that he should have been coming out of that deal. He scheduled everything he did, going to the Western Union office, calling somebody, calling in, so it would have been impossible for him to have been there. I don’t think Ruby wanted to do the shooting. But then he had no other choice. You know, somebody told him what needs to be done. And he knew if he didn’t do it, he could very well have been ground up in a sausage grinder, and all his brothers and sisters and everybody else there.

So its not that simple to just say, “Well I don’t believe I’ll load my gun this morning and go down and shoot somebody.” You don’t have that, you know, you don’t have that choice there.

GD: When Ruby was arrested, after shooting Oswald, Ruby said he did it on his own—

JC: Well, what do you think he’s gonna say?! “Oh, me and Joe Civello, the leader, we own the Carousel Club together, and Civello called me this morning—woke me up, just told me to go down and shoot the deal, and I had to do it.”

They’re not going to say those—

GD: Right.

JC: The only explanation I ever heard he made is, he felt sorry for Mrs. Kennedy and he wanted to show his respect for her. Well, again, you make a comment—and I think other people do—that Ruby makes a statement, and that’s exactly what happened. Well what do you think he’s gonna say, when they catch him red-handed there, and throw him to the floor and cuff him up again? You think he’s gonna make a confession at that time?

GD: No, no. Yeah.

JC: Again, the only fact I know is that Jack Ruby shot Lee Harvey Oswald. Why he shot him, I don’t know. How he got into that place at the time he did, I don’t know. Why the Dallas police department elected to have administrative problems they did that moment that delayed their transfer fifteen or twenty minutes, why that happened, I don’t know. I only know that Jack Ruby had a matter of seconds—not minutes, not hours, not days—he had a matter of seconds, to do what he did, and he had nothing to do with the Dallas police department delaying their transfer by a fifteen or twenty minute period of time.

Ruby wanted to be a very vocal, aggressive, tough-shooting kind of a guy. But he was really just—I don’t know if the Mafia had a ladder or not, but he’d be about as low on the ladder as you could get. But he wanted to be on the top of the ladder. So anybody under him, or anybody subservient to him, an employee or a dancer or anything like that, he’d put on a pretty good show with them you know.

12 Ibid., 189.

(A surprising development is information published in 2013 indicating that New Orleans crime boss Carlos Marcello was the true figure in control of Ruby’s Carousel Club in Dallas: “New information for the first time shows that Carlos Marcello and his organization actually controlled the Carousel Club, not Jack Ruby. Ruby was only the club’s manager.”11 Earlier, FBI memos made available to the Warren Commission had said that Ruby “was well acquainted with virtually every official of the Dallas police force” and was “the pay-off man for the Dallas Police Department.”12)

D: OK. Mr. Hunt was not involved with the Adlai Stevenson incident that happened just before Kennedy arrived, was he? Adlai Stevenson arrived in Dallas and had some people demonstrate against him.

(Former Illinois Governor Adlai Stevenson was the Democratic nominee for president in 1952 and 1956, losing both times to Republican Dwight D. Eisenhower. Stevenson was an intellectual and promoted progressive causes. He was appointed by Kennedy to be US Ambassador to the United Nations. Needless to say he was disliked by the ultraright. On October 25, 1963, Stevenson spoke in Dallas but was heckled by protesters organized by supporters of General Edwin Walker. The situation became uncontrollable and security attempted to get Stevenson out of the building to his car. On the way to the car more protesters outside were waiting. A woman hit Stevenson on the head with a sign and a man spit in Stevenson’s face. Back in Washington, D.C., Stevenson warned Kennedy’s staff about an “ugly and frightening” mood in Dallas, and urged Kennedy not to go to Dallas.)

JC: Well in my book I covered the Adlai Stevenson story. Anytime a person of any renown came into Dallas, especially a political person, all wanted to see Mr. Hunt. Mr. Hunt really had no interest in people of Adlai Stevenson’s level or background or anything like that. But as a businessman, if they came to his office he would normally see them if they came to my office first.

Adlai Stevenson did come to Dallas, and did come to Mr. Hunt’s office. I did visit with him, and Mr. Hunt stepped into my office, they exchanged a few pleasantries. But that’s just the beginning of the story.

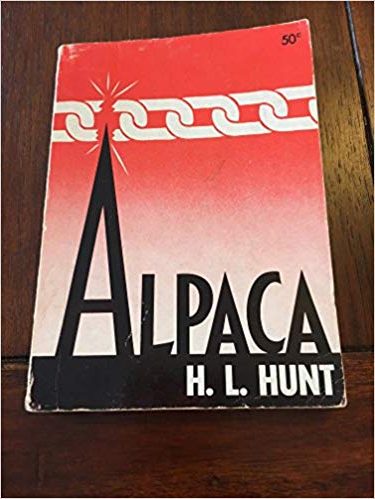

There was a person that came into the office the same day that Adlai Stevenson did. And Mr. Hunt had just written and published a book—his book—called Alpaca. In my book I’ve got the name of the person. But he came in and he wanted to meet Mr. Hunt. And he and I were talking about like you and I are, and Mr. Hunt hollered out and said, “John, who’s that out there?” Well I had the man’s name. And he said, “Well what does he want?” I said, what he wants is an autograph on a copy of Alpaca. Well that’s all Mr. Hunt had to hear. He just dropped everything and he came out and he wanted to meet this fellow, and sign and autograph his book Alpaca. So he comes out and they visit three or four minutes, probably two minutes, something like that, and Mr. Hunt takes his book and autographs it.

Well when that fellow left our office, he goes down on the street. Adlai Stevenson is still down there. And he goes up and spits in his face. I don’t know whether you recall that story or not. It was all over the world.

GD: Same guy?

JC: Yeah. Just left our office, went down and spit in Adlai Stevenson’s face. Well, it was in all the newspapers and the radio and TV, and he got arrested. Well, Mr. Hunt—and we were watching TV together, and they interrupted to show this deal. Well, Mr. Hunt sort of went into a—he didn’t have panics, but he went into a concerned mode. He said, “John,” he said, “I’ve got to get that autographed copy of my book back.”

GD: You were with Mr. Hunt when he saw this on TV?

JC: Well yeah. Yeah. So I said, well I think I can get it back for you. I knew the bell captain pretty well over at the Baker Hotel. And I had one of the girls in the office—this was about 4 o’clock in the afternoon—I had one of the girls in the office call this fellow. And she just called his hotel room and wanted to know if he’d have a drink with her down in the lobby there. So of course he jumped at the opportunity.

And I took her over there. And I was hid around the corner. She went into the lobby, and he came in. And when they sat down, the bell captain took me up to his room, unlocked the door, and locked me in it. And I went through all of his belongings, and found Mr. Hunt’s autographed copy of Alpaca, and took it back to him.

GD: You had pretty versatile job duties.

JC: Well I could <unintelligible> a phone, break into buildings, embezzle <unintelligible>.

GD: Did they teach you that at law school?

JC: No, you learn that through hard knocks.

But anyway, that’s an interesting story. And it could have been a little bit—Mr. Hunt’s concern over him autographing a book for a person that had just spit in the face, is the same theory he had on Lee Harvey Oswald testifying in court, or James Earl Ray testifying in court that he was influenced by Life Line. If the police had gone over there and searched his room and came up with an autographed copy of Mr. Hunt’s book Alpaca, it would have been on all the news services all over the world.

But anyway, that’s an interesting story. And it could have been a little bit—Mr. Hunt’s concern over him autographing a book for a person that had just spit in the face, is the same theory he had on Lee Harvey Oswald testifying in court, or James Earl Ray testifying in court that he was influenced by Life Line. If the police had gone over there and searched his room and came up with an autographed copy of Mr. Hunt’s book Alpaca, it would have been on all the news services all over the world.

GD: Yes.

JC: And Mr. Hunt couldn’t go over and break into his room. And it’s just luck that he left the room at his hotel, left the book in his hotel room, luck that I knew the bell captain over there that would let me into his room there, you know. Nothing planned—it just fell into place there.

When the lady that I employed—not employed, that I worked with—to have a drink with that fellow—I had her sit where his back would be to the exit door, so when I left she saw me, and she got up, excused herself to go to the girls’ room, and left and she never saw him again.

GD: She had never met him before?

JC: No.

GD: How could he take a call from a woman he’s never met?

JC: Well, that happens all the time. She just called, and she didn’t say, “Now I’m so and so, and I work for John Curington and he works for H. L. Hunt and we wanna steal your book.” It wasn’t like that. She just said, “I’ve seen you on TV,” or something like that, “and I’d like to have a drink with you.”

GD: OK.

JC: That simple, nothing complicated—no planned deal or anything like that. Just an—an orangutang could come up with that kind of a theory.

GD: Not too complicated.

JC: Yo.

GD: The Adlai Stevenson incident happened less than a month before the Kennedy assassination.

. . . . . . [continuing in next installment]

If you enjoyed this post, please consider donating to Vridar. Thanks!

Mr. Curington’s remark to me in the interview above that if Ruby did not follow what Curington believed was an order from someone to kill Ruby, that “he [Ruby] could very well have been ground up in a sausage grinder”, prompts this comment from me.

Curington may have meant that as simply a general figure of speech referring to Mob violence, but I later noticed an eery evocation of a curious detail I picked up in my reading. There was a prominent Dallas restauranteer at the same time named Joseph Campisi, who was considered #2 local Mob person in Dallas next to Civello, and after Civello’s death in 1970 succeeded Civello as the new #1. Campisi had personal and telephone contacts with Marcello, the Mob boss in New Orleans who also controlled Dallas. After Ruby shot and killed Oswald, Campisi was Ruby’s first visitor to Ruby in jail.

With that background, there is this detail from Campisi’s testimony when Campisi was questioned by the House Select Committee on Assassinations in 1978 (transcript is at http://jfkassassination.net/russ/m_j_russ/hscacamp.htm):

Campisi: “. . . The next time I was invited to the opening of Broussard’s Restaurant [in New Orleans], and I met him [Marcello] there. I had talked to him on the phone a couple of times. He has called me and asked me if I needed any crab claws or softshell crabs, and every year I send them sausage, 260 pounds of Italian sausage that I send to them for Christmas to give to all of the brothers and what friends I have there. I send like 260 pounds of sausage every year that I make special with walnuts and celery.”

Q: “Is there some reason why you send him 260 pounds to divide between everybody?”

Campisi: “No. No. I send each brother, and then I have a lot of cousins there. I have a lot of relatives there, and I send sausage to all of them.”

What I noticed, which I have never seen attention called to in print, is that 260 pounds is the weight of a corpse. Disposal of bodies such that they cannot be found by authorities is always a technical challenge in Mob killings. It sounds macabre, but I would be curious to know whether anyone at Marcello’s end actually ate that sausage.

The Warren Commission, which concluded against what Warren Commission member Sen. Russell Long said was the wishes of a majority of itself, that Oswald had acted alone, claimed to have found no evidence that Oswald’s killer Jack Ruby was Mob connected. The following may be of interest from David Scheim, Contract on America: The Mafia Murder of President John F. Kennedy (New York, 1988), pp. 98-99:

[On pp. 174-175 of the Scheim book, which can be seen on Google Books, a visually striking comparison can be seen of photographs side by side of the complete version of the FBI interview in the National Archives, and the earlier published shortened version in the Warren Commission Exhibit with final paragraphs inexplicably missing.]

One more item of interest. In the interview Mr. Curington reconstructs that Jack Ruby, the killer of Oswald, did not want to kill Oswald but had no choice. The following detail, not mentioned by Curington, lends support to that interpretation.

As recounted by Dallas Police officer Billy Grammer in this Utube video (https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=kEjT7XCN_R0), Officer Grammer was a dispatcher on duty at the Dallas police night desk the night before Oswald was killed. Grammer received a phone call about 3 a.m. that night from an anonymous caller warning that Oswald would be killed the next morning when Oswald was scheduled to be transferred. The anonymous caller said the time of Oswald’s transfer must be changed or else “we [the anonymous caller] are going to kill him [Oswald]”. The warning, although immediately reported to higherups, went unheeded, the transfer of Oswald proceeded, and Oswald was shot to death by Ruby during that transfer. Officer Grammer said that the caller knew details of the planned transfer. When Grammer asked the caller who he was, the caller replied, “I can’t tell you that but you know me.” After Ruby shot Oswald, Grammer realized that the caller he had spoken to was Jack Ruby.

A separate, different video of Billy Grammer telling the same account can be seen starting at about 1:06:44 in this 1988 Jack Anderson TV documentary here: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=fvpCoOwz3dI.

A DPD retired vice detective. Name Rowe told me Ruby paid him and other police for rides around the city. The police dispatcher would call him with a code name for Ruby. He was paid $50. Which was a good tip back then. Ruby also made a few car payments for him.