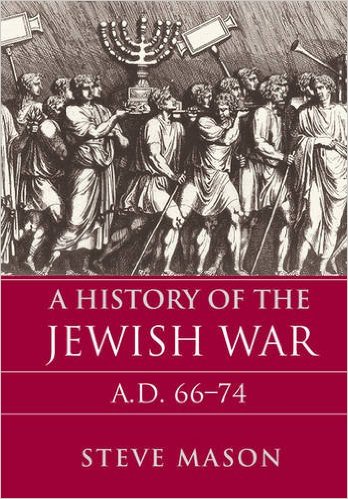

A historian specializing in the study of Josephus, Steve Mason, presents a case that the war that led to the destruction of Jerusalem and its temple was not prompted by any messianic movement among the people of Judaea. Rather, Mason suggests that the prophecy of a ruler to come out of the east and rule the entire world was a product of hindsight and that there is little reason to think that there was a “messianic movement” propelling the Jews to rebel against Rome.

A historian specializing in the study of Josephus, Steve Mason, presents a case that the war that led to the destruction of Jerusalem and its temple was not prompted by any messianic movement among the people of Judaea. Rather, Mason suggests that the prophecy of a ruler to come out of the east and rule the entire world was a product of hindsight and that there is little reason to think that there was a “messianic movement” propelling the Jews to rebel against Rome.

I can’t hope to cover the full argument set out by Mason in A history of the Jewish War, AD 66-74 in a single post but I will try to hit some key points from pages 111 to 130 here.

To begin. It is a misunderstanding to think that we can read the works of Josephus as if they were a chronicle of facts happily shedding light on the background to the rise of Christianity.

History as Tragedy

To get the most reliable data from Josephus we need to study his works in the context of other historical writings of his day. In that context it is evident that Josephus is writing a “tragic history” — a narrative that he presents as a tragedy, a form of narrative with which his Greco-Roman audience was familiar. As a tragedy Josephus seeks to elicit tears of sympathy from his audience by using all of his rhetorical skills to portray graphic suffering and misfortune. In War Josephus opens with the proud Herod whose hubris is brought low by the misfortunes that follow. The audience knows how the story ends and knowing that only adds to their awareness of the tragedy in each scene. The irony of temple slaughter at Passover time would have been as clear to Roman as to Jewish readers: Passover was known to have been the festival of liberation.

A tragedy needs villains and Josephus fills his narrative with an abundance of “robbers” or “bandits” who polluted the temple, just as per Jeremiah 7:11 said they would.

“Has this house, which is called by my name, become a den of robbers in your eyes?”

Josephus was in good literary company since we find the same motif being drafted by the Roman historian Tacitus when narrating the destruction of the central temple in Rome:

Thus the Capitoline temple, its doors locked, was burned to the ground undefended and unplundered. This was the most lamentable and appalling disaster in the whole history of the Roman commonwealth. Though no foreign enemy threatened, though we enjoyed the favour of heaven as far as our failings permitted, the sanctuary of Jupiter Best and Greatest solemnly founded by our fathers as a symbol of our imperial destiny . . . was now, thanks to the infatuation of our leaders, suffering utter destruction. (Hist. 3.72 — I am using my Penguin translation and not the one used by Mason)

Josephus blends Jewish and Greek literary motifs in his tragic narration (Mason, pp. 114-121). A stock motif in tragic narrative were omens of imminent disaster and ambiguous prophecies that would mislead the hapless victims.

Tragedy’s Stock Omens and Prophecies

A motif that was virtually universal in ancient historiography was that a change of ruler should be preceded by omens and prophecies. We see it in the history of Tacitus describing the ascent of Vespasian (I quote from LacusCurtius, Histories, Book 2.78- the extract is not quoted by Mason): Continue reading “Is Josephus Evidence that a Messianic Movement caused the Jewish War?”

Like this:

Like Loading...