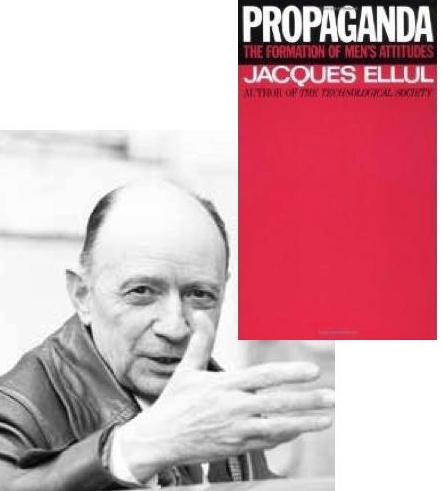

Professor James D. Tabor (The Jesus Dynasty) has done his field of biblical studies and, most especially, the wider public a great service by setting out the historical methods by which he and critical scholars more generally approach the gospels. The public deserves to know and the field of biblical studies can only benefit from a more informed public. In Picking and Choosing: How Scholars Read the Gospel Tabor explains that scholars don’t merely “pick and choose” details in the different gospels according to what they feel supports their theories about the historical Jesus or other questions: they apply critical analysis. Example:

Why do we have differing versions of many of Jesus’ teachings and sayings in Matthew and Luke that are not in Mark . . . ? Rather than picking ones “favorite” version, and using it arbitrarily for ones own purposes, what critical scholars attempt to do is analytically account for the various strands of tradition, carefully comparing the similarities and differences, in an effort to get at why our traditions differ, when and where they originated, and which might more reliably go back to Jesus himself – if such can be determined.

Notice something else, though. The entire explanation is couched in the an assumption that the gospels contain traditions that in some cases and in some form go back to the historical Jesus himself. In fact, one significant purpose of the critical analysis is to discover what gospel material “might more reliably go back to Jesus himself”.

That is, the gospels are assumed to contain records, however flawed, of event or sayings that emanated from Jesus and/or his followers. The gospels are assumed at some level to be based on a “true story”.

Reasonable assumptions

That is a very reasonable position to take. After all, the gospels are written in an authoritative tone from the perspective of an all-knowing narrator. The narrative voice conceals the real identity of the true author and in doing so removes any sense that we are reading a narrative limited by human bias and perspective. Of course, scholars especially are keenly aware that the stories are definitely, even inevitably, written from personal perspectives, and that’s the reason for their need to critically analyse their contents. But the problem is we have grown up in a culture that has taken for granted the authoritative character of the Gospels. Western religious and broader cultural tradition is grounded in the assurance that Jesus was the most important influence on our religious ideas and cultural values. To question this “fact” is as crazy as questioning the rotundity of the earth. Institutions have been built on the belief in Jesus as portrayed in the Gospels. The “fact of Jesus” and “Gospel Truth” are part of our everyday metaphors and consciousness. Jesus is held up as a legitimizing symbol for a whole range of social, political, ideological causes.

Further, we have the date of the earliest gospel grounded in our conventional understanding:

Mark seems to have been written around 70 CE – within forty years of Jesus’ lifetime.

This is taken as a given, again quite reasonably, because it is a near-consensus among New Testament scholars. There are some outliers who place it considerably earlier, even decades earlier, but most (not all) of those who do so are apologists. Even fewer mavericks place it much later.

The problem is that these assumptions are not facts and really are open to question.

Look first at our assumption about the nature of the Gospels, that they are at some level records of a “true story”. Some scholars have argued that many of the narrative units about Jesus are re-writes of Old Testament passages. The raising of the daughter of Jairus is seen by some to be a re-write of similar miracles by Elijah or Elisha. Other scholars (the best known one is Dennis MacDonald and his The Homeric Epics and the Gospel of Mark) have even argued that both anecdotes and entire themes in the Gospels are drawn from popular Greek literature. Now other scholars have challenged such interpretations but the point is that such arguments can be reasonably made by specialists who know their stuff. In other words, it is not a bed-rock unquestionable certainty that what we read in the Gospels necessarily at some level owed its origin to “traditions” that were believed to have come from the historical Jesus.

It is not beyond possibility that at least parts of the Gospels originated as creative writing, as literary inventions. Of course some parts were definitely drawn from genuine historical tradition, too. We know that Pilate really was the governor, etc.

So given such a possibility, how do historians decide what is drawn from “historical memory” or even “historical imagination” on the one hand and “literary creativity” on the other?

This question is going one step further than Tabor has addressed. We are not asking what accounts in the Gospels can be traced to Jesus, but how we can tell if anything in a text owes anything at all to history as opposed to being entirely creative literature.

I believe there are ways. Not ways that will guarantee certainty, but that will certainly give us some measure of confidence one way or the other.

How we can write ancient history — breaking through cultural assumptions

The first is to look for independent corroboration. Some scholars see corroboration for their view that Gospel stories such as the raising of Jairus’ daughter above are literary fabrications by pointing to similar accounts in the Hebrew Bible. The critical point is that the corroborating evidence must be genuinely independent.

A second condition is to look at the provenance of both the narrative under investigation and of the corroborating testimony. Do we have clear reasons to trust that a piece of writing is derived from someone who “knew his history” or at least “the historical traditions”? Or do we have reason to believe the author was creative — for whatever theological or parabolic or edifying or entertainment reasons — from the start? So we may not have contemporary written accounts of Hannibal or Alexander the Great but we do have accounts by persons known who identify their sources from the times in question. Of course in theory they could all be lying, but their accounts do cohere with other evidence we see and do explain a lot about the way we can see the world changed so I think they are entitled to have at some measure of our confidence.

Unfortunately we have no idea who wrote the gospels or why or for whom or when (I’ll discuss the “or when” below). They don’t even identify their sources. The prologue introducing the Gospel of Luke is too vague a formula to be useful, and it is also questionable whether it is even meaning to say what most people seem to think it means. That’s never a good start for any historian. The reason we can write a history of the ancient world is precisely because we do have sufficient sources of the type that can be verified or give us some confidence in their historical reliability (imperfect though it may be). We can talk about Socrates as a historical figure because we do have such evidence for him.

When it comes to the Gospels, however, we have no comparable corroborating evidence nor the sort of information that should assure us that they really are attempts to record historical traditions and memories.

We do have evidence that supports the view that they were cut from the cloth of other literature, however.

The ideological influence on the dating of the Gospels

As for when the first Gospel was written, again we see cultural assumptions guiding our interpretations of the evidence. We assume, as we have always assumed and as everyone around us has always assumed, that at some level they are based on genuine history. Given that we believe this is what the Gospels are, it follows that they become the more reliable the closer we can legitimately place their origin to those historical events.

Therefore when we read about the prediction of the fall of the Jerusalem temple in the Gospel of Mark, it is again reasonable to date that Gospel to some time after that event. But of course we can infer that historical reliability as a rule tends to diminish the further away it is placed from the time it relates. In fact there is no reason I know of (I can be corrected, of course) that the Gospel of Mark might not have been written some time in the early decades of the second century. The earliest independent evidence of its existence appears to be found in a writing by Justin Martyr dated shortly after the Bar Kochba war of the early 130s.

The outsider perspective

James Tabor has done everyone a service by setting out so clearly the critical approaches and assumptions at the core of studies exploring Christian origins. I think we as outsiders can use his post as a springboard to identify more clearly the cultural assumptions embedded in the scholarly methods of critical New Testament scholars.

Like this:

Like Loading...