First, immerse every person in their own cyber-world where their environment identifies their interests and biases.

Second, feed every person with the news and data that reinforces their biases. Masses and masses of data that serve that purpose. Too much data to critically analyse. So much data that swamps each person with confirmation of their belief systems about the world. Result? Too often, paralysis.

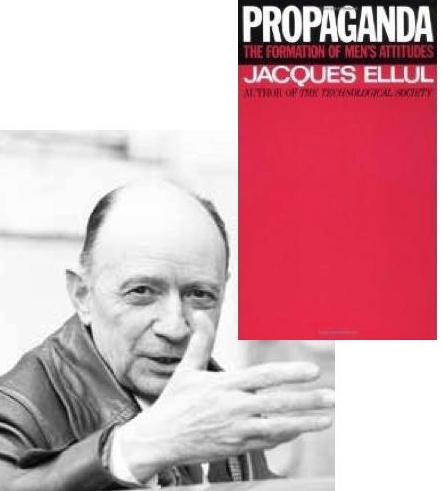

And much of the information disseminated nowadays — research findings, facts, statistics, explanations, analyses — eliminate personal judgment and the capacity to form one’s own opinion even more surely than the most extravagant propaganda. This claim may seem shocking; but it is a fact that excessive data do not enlighten the reader or the listener. They drown him. He cannot remember them all, or coordinate them, or understand them; if he does not want to risk losing his mind, he will merely draw a general picture from them. And the more facts supplied, the more simplistic the image. If a man is given one item of information, he will retain it; if he is given a hundred data in one field, on one question, he will have only a general idea of that question. But if he is given a hundred items of information on all the political and economic aspects of a nation, he will arrive at a summary judgment — “The Russians are terrific!” and to on.

A surfeit of data, far from permitting people to make judgments and form opinions, prevents them from doing so and actually paralyzes them.

(Ellul, Propaganda, 87)

That was written in 1962!! How much frighteningly truer must it be today!

How to fight back in such a dystopian world?

If we believe that we keep ourselves well-informed enough to keep a level head, beware. There is a hidden trap.

To the extent that propaganda is based on current news, it cannot permit time for thought or reflection. A man caught up in the news must remain on the surface of the events he is earned along in the current . . . .

We are more liable to fall into the trap if we think we can recognize or with little effort sift the lies from the truth. This confidence leads to two attitudes:

The first is: “Of course we shall not be victims of propaganda because we are capable of distinguishing truth from falsehood.” Anyone holding that conviction Is extremely susceptible to propaganda, because when propaganda does tell the “truth,” he is then convinced that it is no longer propaganda, moreover, his self-confidence makes him all the more vulnerable to attacks of which he is unaware.

The second attitude is: “We believe nothing that the enemy says because everything he says is necessarily untrue.” But if the enemy can demonstrate that he has told the truth, a sudden turn in his favor will result. . . .

(Ellul, 46, 52)

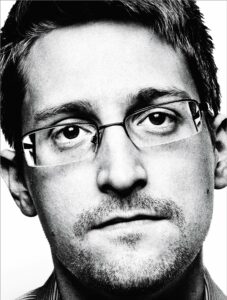

Remember Popper and what he had to say about the necessity to seek to falsify what we think to be true. Edward Snowden a few months ago made the same point:

Here’s a better way to think: in an . . . information-glutted world where you can basically find evidence for any theory you want, where people inhabit separate online realities, we should focus on falsifiability (which can be tested for) over supportability (which cannot).

(Snowden, Apophenia)

Do we sense that events are out of control? That the government is an evil force and we are all helpless before it? That nuclear war with China is inevitable? That covid-19 is just the opening salvo of more serious epidemics? That the conditions that made human civilization possible are fast being ripped away from us through climate change? It’s easy to become overwhelmed into inaction.

That feeling is akin to believing in all-powerful hidden forces behind the institutions that shape our lives and there is nothing we can do to change them. Here is where conspiracy theories enter the picture:

This what what the Austrian Jewish sociologist Karl Popper, refugee of the Holocaust in New Zealand and later England, laid out in his theory of science. Popper believed conspiracy theories are exactly what feeds a totalitarian state like Hitler’s Germany, playing on and playing up the public’s paranoia of The Other. And authoritarians get away with it precisely because their pseudoscientific claims, masquerading as sound research, are designed to be difficult to prove “false” in the heat of the moment, when data sets — not to mention a sense of the historical consequences — are necessarily incomplete.

By Popper’s lights—and, I’d argue, by the intuition of basic human decency—we shouldn’t consider these provisional theories “science” at all.

(Snowden, Apophenia. This is the second time I’m drawing upon the same Edward Snowden article.)

Of course, when we take some time to delve into how these institutions actually work (and we have addressed the institution of the media a few times here) we find that people in them too often find themselves spreading consequences they personally would not like, or that they make themselves believe are not so malign after all:

Popper’s a favorite in conspiracy theory studies, but I want to bring in an adjacent idea of his that I think is underemphasized in this context, which is that most human actions have unintended consequences. Instant advertising was supposed to yield informed consumers; the National Security Agency was supposed to protect “us” by exploiting “them.” These plans went horribly wrong. But once you wake up to the idea that the world has been patterned, intentionally or unintentionally, in ways you don’t agree with, you can begin to change it.

(Snowden, Apophenia)

Alone, we can do nothing significant, it is true. But we are social beings. Solitary confinement, as posted about recently, sends us insane.

It is in good faith that whistleblowers around the world bring these contradictions to public attention; they facilitate public epiphany, reminding us that we’re not quarantined in our private, paranoid “stages.” Thinking in public, together, allows us to stage a different performance entirely. We become more like Popper’s social theorists:

(Snowden, Apophenia)

That’s it. Thinking in public. Being socially engaged. Understanding the world around us requires some effort to pull ourselves over to the bank to stop being carried along in the current that Ellul spoke of. Following is a passage from an essay by Popper.

It is the task of social theory to explain how the unintended consequences of our intentions and actions arise, and what kind of consequences arise if people do this that or the other in a certain social situation. And it is, especially, the task of the social sciences to analyse in this way the existence and the functioning of institutions (such as police forces or insurance companies or schools or governments) and of social collectives (such as states of nations or classes or other social groups). The conspiracy theorist will believe that institutions can be understood completely as the result of conscious design; and as collectives, he usually ascribes to them a kind of group-personality, treating them as conspiring agents, just as if they were individual men. As opposed to this view, the social theorist should recognize that the persistence of institutions and collectives creates a problem to be solved in terms of an analysis of individual social actions and their unintended (and often unwanted) social consequences, as well as their intended ones.

(Popper, “Conspiracy Theory of Society”, 15. Snowden cites the last part of this same paragraph in Apophenia)

Is this naive optimism?

Maybe I’m the deluded one for finding reason for optimism in this idea—and not only because it saves me from letting the former Nazi Conrad have the last word. Popper’s thinking offers an escape hatch from our private worlds and back into the public sphere. The social theorist is a public thinker, oriented toward improving society; the conspiracy theorist is a victim of institutions that lie beyond their control.

(Snowden, Apophenia)

As Noam Chomsky has said, there is no alternative to optimism. Pessimism leads to disengagement and disengagement guarantees the worst outcome.

Optimism is a strategy for making a better future. Because unless you believe that the future can be better, it’s unlikely you will step up and take responsibility for making it so. If you assume that there’s no hope, you guarantee that there will be no hope. If you assume that there is an instinct for freedom, there are opportunities to change things, there’s a chance you may contribute to making a better world. The choice is yours.

(Chomsky, On Choosing Optimism)

Ellul, Jacques. Propaganda: The Formation of Men’s Attitudes. Translated by Konrad Kellen and Jean Lerner. New York: Vintage, 1973. https://archive.org/details/propagandaformat0000ellu

Popper, Karl. “The Conspiracy Theory of Society.” In Conspiracy Theories: The Philosophical Debate, edited by David Coady, 13–15. Aldershot, Hampshire, England ; Burlington, VT: Routledge, 2006.

Snowden, Edward. “Apophenia.” Substack newsletter. Continuing Ed — with Edward Snowden (blog), August 6, 2021. https://edwardsnowden.substack.com/p/conspiracy-pt2.

Sustainably Motivated. “Noam Chomsky On Choosing Optimism,” March 12, 2017. https://sustainablymotivated.com/2017/03/12/noam-chomsky-choosing-optimism/.