David Fitzgerald and Neil Godfrey discuss the Christ Myth Theory with Phil Robinson of Nuskeptix.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=guwnqgJqvHA&start=31

Musings on biblical studies, politics, religion, ethics, human nature, tidbits from science

David Fitzgerald and Neil Godfrey discuss the Christ Myth Theory with Phil Robinson of Nuskeptix.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=guwnqgJqvHA&start=31

For a refreshing perspective read Tom Dykstra’s post on his reflections after reviewing books by Thomas Brodie and Bart Ehrman: Humor in Biblical Studies.

Dykstra’s post begins. . . . .

Almost a year ago I finished expanding my posts on Brodie’s Jesus-didn’t-exist book and Ehrman’s yes-he-did book into an article for an academic peer-reviewed journal, to be published later this year. As I did more research on this controversy, one aspect of it struck me forcefully: many or most people on both sides of the fence were remarkably intolerant and contemptuous of the other side.

In what you might think of as an “academic” debate why should people get so incensed at and abusive toward those who disagree? . . .

In reading and thinking about this issue I reached a conclusion that may sound counter-intuitive: the very best biblical scholars are those that maintain a sense of humor toward their subject matter and toward those who disagree with them. . . . The issue is this: I see contemptuous and abusive language as evidence that the perpetrator likely has some kind of vested interest in a particular belief about the subject. . . . (my bolding)

He then discusses another one of my favourite scholars, Michael Goulder. Read the thing in full and forward it to anyone you think gets a bit too cranky: Humor in Biblical Studies — and maybe not just to biblical scholars. I’m thinking of course of my recent slap down by a certain evolutionist for my question asking him why he shunned the scholarly approach of his peers towards Islamic terrorism.

Speaking of humour and the “which belief is right” debate, this has just appeared on John Loftus’s Debunking Christianity site:

The following response by Dr Hector Avalos to Dr Robert Myles‘ review of The Bad Jesus was originally posted on Debunking Christianity and is reposted here with permission.

By Dr. Hector Avalos

Dr. Robert Myles of the University of Auckland (New Zealand) has reviewed The Bad Jesus in two parts available here and here.

He is the first biblical scholar to perform such a review of The Bad Jesus on the blogosphere. I was especially interested in his comments because he specializes in New Testament and Christian origins, as well as in Marxism and critical theory.

Myles is also the author of The Homeless Jesus in the Gospel of Matthew (Sheffield: Sheffield Phoenix Press, 2014), which treats a few of the subjects I do.

Myles is also the author of The Homeless Jesus in the Gospel of Matthew (Sheffield: Sheffield Phoenix Press, 2014), which treats a few of the subjects I do.

That book offers many provocative observations, and I recommend it to anyone interested in issues of poverty and homelessness in the Bible. His book came to my attention too far into the editing process of my book, and I did not include it in my discussions. I did read it by the time I wrote this post.

Although Myles’ review raises some interesting questions, it ultimately does not represent my arguments very accurately or address them very effectively. I will demonstrate that his review actually is, in part, an androcentric defense of the abandonment of families by Jesus’ disciples. I will address the objections he raises against my methodology and my discussion of Jesus’ view of abandoning families, especially in the case of the men he called to be his disciples in Mark 1:16-20 because that is one main example Myles chose from my book.

To understand how Myles misrepresents or misunderstands the purpose and method of my book, it may be useful to begin with the introductory summary of the book that I provided on pages 8-9 of The Bad Jesus:

To understand how Myles misrepresents or misunderstands the purpose and method of my book, it may be useful to begin with the introductory summary of the book that I provided on pages 8-9 of The Bad Jesus:

Myles diverts his attention from my stated purposes to a critique of neoconservative or capitalists ideologies. Such critiques of neoconservatism or modern capitalism may be sound, but they are not the most relevant to my argument about how Jesus is treated in New Testament ethics. According to Myles:

Methodologically, Avalos’ book is weak, which is unfortunate as I think the broader argument has a lot of merit. Avalos self-identifies as a a [sic] New Atheist. This perspective holds that theism is generally destructive and unethical. It is embodied for example in the writings of Richard Dawkins, Sam Harris, and Christopher Hitchens. What Avalos doesn’t explore is how this movement has also tended to form strong associations with a neoconservative political ideology, perhaps expressed most triumphantly by the late Christopher Hitchens. In and of itself this might not appear overly relevant, but its importance will become obvious shortly.

There are two problems with this criticism. First, Myles left out that I identified myself with a “Second Wave” of New Atheism on p. 15 of The Bad Jesus:

So, perhaps, one can view atheist biblical scholars as ‘Second Wave New Atheists’ to contrast with the non-biblical scholars that dominated the first wave. Readers should view the present work as the first systematic New Atheist challenge to New Testament ethics by a biblical scholar.

Indeed, I explicitly named Dawkins, Hitchens, Harris as being part of that First Wave from which I was differentiating myself.

My agreement with the New Atheism was qualified as follows: “Insofar as I believe that theism is itself unethical and has the potential to destroy our planet, I identify myself with what is called ‘the New Atheism” (p. 13). Myles’ review erroneously assumes that I identify with the New Atheism insofar as every other ideological or capitalist feature he identifies.

Continue reading “Hector Avalos Responds to Robert Myles’ Review of The Bad Jesus“

Terrorism is evil. Murder is evil. Torture is evil. Hate crimes are evil. War is evil. Attempt to seriously understand why they happen, however, and one risks being accused of supporting evil.

On this blog I have attempted to share some insights of scholarly research into terrorism and the background to the Israeli-Palestinian conflict and have in consequence mistakenly been thought to be justifying terrorism, of being an apologist for Islam, of anti-semitism and of hatred towards Israel. All of those things are completely untrue but the accusations persist because some readers view my explanations as taking the evil-doer’s side.

Why does this happen? Steven Pinker offers a cogent explanation in The Better Angel of Our Nature:

Baumeister notes that in the attempt to understand harm-doing, the viewpoint of the scientist or scholar overlaps with the viewpoint of the perpetrator.

Both take a detached, amoral stance toward the harmful act. Both are contextualizers, always attentive to the complexities of the situation and how they contributed to the causation of the harm. And both believe that the harm is ultimately explicable.

The viewpoint of the moralist, in contrast, is the viewpoint of the victim. The harm is treated with reverence and awe. It continues to evoke sadness and anger long after it was perpetrated. And for all the feeble ratiocination we mortals throw at it, it remains a cosmic mystery, a manifestation of the irreducible and inexplicable existence of evil in the universe. Many chroniclers of the Holocaust consider it immoral even to try to explain it.

Pinker, Steven (2011-10-06). The Better Angels of Our Nature: The Decline of Violence In History And Its Causes (pp. 495-496). Penguin Books Ltd. Kindle Edition.

Baumeister, with psychological spectacles still affixed, calls this the myth of pure evil. The mindset that we adopt when we don moral spectacles is the mindset of the victim. Evil is the intentional and gratuitous infliction of harm for its own sake, perpetrated by a villain who is malevolent to the bone, inflicted on a victim who is innocent and good. The reason that this is a myth (when seen through psychological spectacles) is that evil in fact is perpetrated by people who are mostly ordinary, and who respond to their circumstances, including provocations by the victim, in ways they feel are reasonable and just.

The myth of pure evil gives rise to an archetype that is common in religions, horror movies, children’s literature, nationalist mythologies, and sensationalist news coverage. Continue reading “The Risks of Understanding and Explaining Evil”

Throughout the books of the Hebrew Bible (the Christian’s “Old Testament”) one finds assurances for readers that the stories (or histories) being told are detailed in other written sources. Readers are further assured in a number of cases in the books of Kings and Chronicles that even more details can be found in outside sources.

That sounds authoritative. Surely only a “hyper-sceptical” cynic would insist that such source citations were fabricated and the narratives have no credible foundation whatsoever.

But there is a more prudent alternative to having to choose between either/or. We have no independent evidence for the existence of these cited sources but of course that does not mean they never existed.

Are we going a step too far, however, to wonder if they never existed at all and that our biblical authors really did fabricate at least some of them? How could we possibly know?

No, we are not going too far to seriously ponder the question because scholars do have good reasons for believing that in the ancient world historians of the day did indeed sometimes pretend to cite real sources that in fact did not exist.

If I begin to set out reasons for suspecting that in some cases the biblical authors were making up sources I run the risk of being accused of having some sort of hostile agenda against the Bible and religion generally. So let’s examine the evidence for other ancient historians fabricating their sources. If we start with the extra-biblical world then we can show that we are analysing the Bible by the same standards we apply to other ancient texts and every reasonable person will happily acknowledge our even-handedness.

One more caveat. Merely identifying grounds for the possibility that source citations are fictions does not mean they “probably” are. What it does mean is that no secure argument or conclusion for a narrative’s reliability can be built upon the presence of source citations.

This post elaborates with a few in depth case-studies on the point I made earlier where I listed examples demonstrating that it was not unusual for ancient historians to fabricate their source-claims.

Herodotus writes in his Histories (book 2):

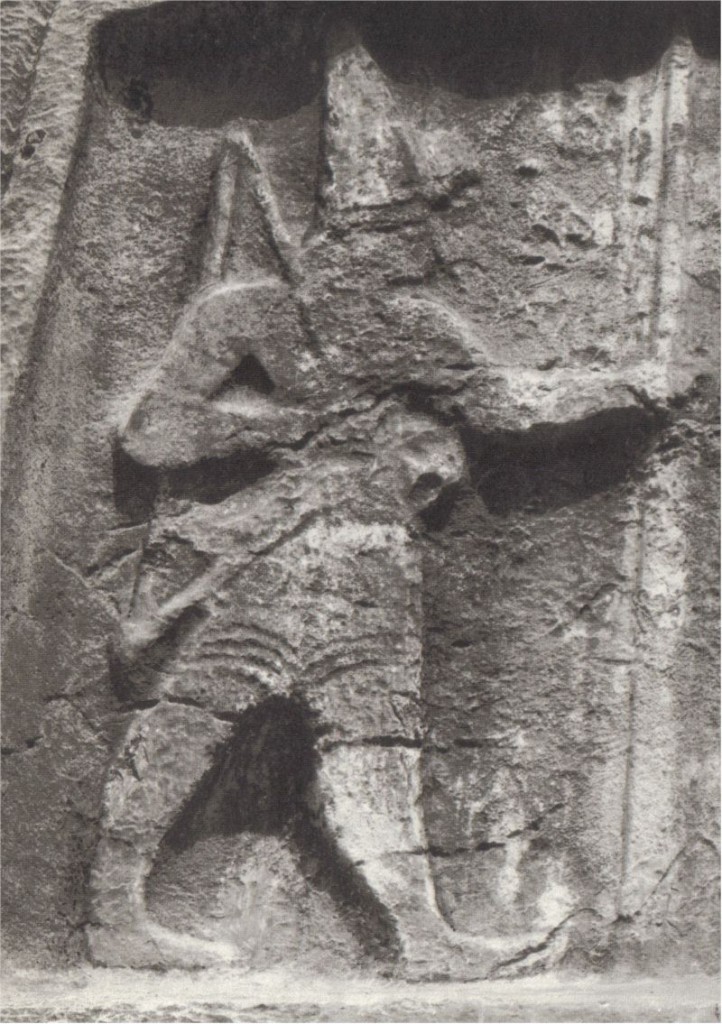

As to the pillars that Sesostris, king of Egypt, set up in the countries, most of them are no longer to be seen. But I myself saw them in the Palestine district of Syria, with the aforesaid writing and the women’s private parts on them.

[2] Also, there are in Ionia two figures of this man carved in rock, one on the road from Ephesus to Phocaea, and the other on that from Sardis to Smyrna.

[3] In both places, the figure is over twenty feet high, with a spear in his right hand and a bow in his left, and the rest of his equipment proportional; for it is both Egyptian and Ethiopian;

[4] and right across the breast from one shoulder to the other a text is cut in the Egyptian sacred characters, saying: “I myself won this land with the strength of my shoulders.” There is nothing here to show who he is and whence he comes, but it is shown elsewhere.

[5] Some of those who have seen these figures guess they are Memnon, but they are far indeed from the truth.

There are indeed two statues still to be seen at the Karabel Pass on the old road from Ephesus to Smyrna. Unfortunately for Herodotus’s credibility

I have taken the above from Katherine Stott’s Why Did They Write This Way? The main inspiration for this post and the five specific case-studies are based on Stott’s chapter 2 of that book. (I should stress that Stott’s interest is not to suggest fabrication of sources was the general rule.)

Stephanie West in “Herodotus’ Epigraphical Interests” (The Classical Quarterly, Vol. 35, No. 2 (1985), pp. 278-305) writes:

Herodotus here describes the well-known reliefs of the Karabel pass, which depict a Hittite war-god of extremely un-Egyptian appearance. . . .

If Herodotus had seen even a fraction of the Egyptian monuments he claims to have done, he could never have supposed the Karabel reliefs to be Egyptian had he actually visited the site. (West, p. 301)

I like West’s comment on the way illusory way Herodotus so easily persuades readers that he writing an authoritative and reliable account: Continue reading “Ancient Historians Fabricating Sources”

Recently we looked at Tom Holland’s interest in “de-radicalising Muhammad” and today part one of an online interview with Hector Avalos has appeared in which he discusses his new book The Bad Jesus in which he exposes the “low-down” on Jesus. Just as Holland argues for the importance of promoting an understanding of what can and cannot be known about Muhammad, Avalos argues that the Christian bias of New Testament scholars has driven them to put a superior ethical spin on acts and sayings of Jesus that are in fact antithetical to today’s ethical norms.

Recently we looked at Tom Holland’s interest in “de-radicalising Muhammad” and today part one of an online interview with Hector Avalos has appeared in which he discusses his new book The Bad Jesus in which he exposes the “low-down” on Jesus. Just as Holland argues for the importance of promoting an understanding of what can and cannot be known about Muhammad, Avalos argues that the Christian bias of New Testament scholars has driven them to put a superior ethical spin on acts and sayings of Jesus that are in fact antithetical to today’s ethical norms.

Avalos explains that The Bad Jesus is actually a sequel to The End of Biblical Studies.

Biblical studies is still part of an ecclesiastical academic complex, very biased toward the Christian viewpoint in particular, and religionist throughout. Biblical scholars are there to promote the value of the Bible because in part it is self-serving. It furthers their own profession to be biblical scholars. And if the Bible has no value then what use is there for Biblical studies. . .

A religionist, “in particular Christian orientation”, permeates the field of Biblical studies and Avalos observes that the subfield of Christian ethics is the most biased of all. The ethical superiority of the purported founder of Christianity is the lodestone of the scholars involved. In Avalos’s mind the reason for this is that most scholars continue even today to view Jesus through the lens of Chalcedon and Nicea. Though they claim to be studying the historical Jesus they nonetheless still see Jesus as divine.

This should not be a controversial statement to anyone who has read a wide range of historical Jesus studies. Even “liberal Christian” scholars have made little effort to hide their belief that Jesus is alive today and that they regularly commune in some manner with him.

An interesting biographical detail we learn is what led Hector Avalos to undertake formal studies in the Bible after becoming an atheist. Continue reading “De-Sacralizing Jesus”

H/t Otagosh — See the Triangulations blog for nine functions the author believes religion accomplishes for believers: Religion as Moral Signalling. This follows from my previous post that views religion (Islam, Christianity — any of them) as social creations with social functions. The doctrines and practices are not the end but the means to the ends. A graphic highlights nine needs met by religion — listed here from Otagosh’s summary:

“What do the Charlie Hebdo murders and the rise of the Islamic State owe to Islam? It would be comforting to insist, as many have done, that they owe nothing at all; but Holland, in the inaugural Christopher Hitchens Lecture, argues that the truth is more complex. The best way to combat jihadism, he proposes, is to recognise the centrality of Muhammad to Islam – and that he comes in many forms. There is the moral leader who swallowed abuse peaceably; and there is the war leader who ordered people who insulted him put to death. How best, then, to de-radicalise the Prophet? Tom Holland is author of In The Shadow of the Sword, Rubicon, Persian Fire, Millenniumand the new translation of The Histories by Herodotus. Chaired by Katrin Bennhold of the New York Times.” — from the Hay Festival program.

Denouncing Islamic State as not representing “true Islam” is a well-intentioned declaration but counterproductive and seriously problematic, according to historian Tom Holland in the inaugural Christopher Hitchens Lecture at the May 2015 Hay Festival. The title of his talk is De-Radicalising Muhummad (available online).

What is wrong with these well-meaning efforts to defuse anti-Islamic tensions?

What it does is imply that there is a normative, authentic Islam, one that embodies ideals that are perfectly compatible with liberal, secular Britain, and then there are misinterpretations of it, distortions of it, that are not really Islam at all. . . . .

By denying the title of Muslims to Islamic State Western governments are actually playing the same lethal game as the Islamic State themselves. Because what the Islamic State do is to condemn other Muslims as either apostates or heretics — the better then to justify their elimination.

I really don’t think it is for Prime Ministers or Home Secretaries to play that game. Because once you take it on yourself to define what is or isn’t authentic Islam then you are buying into the notion that such a thing as authentic Islam actually exists.

Now if you’re a believer of course that’s fine. You will accept that indeed Islam was given to you by God and therefore it does have some absolute Platonic essence.

But if you’re not a believer then a religion is just like any other manifestation of human culture. It’s something that is porous, variable, forever mutating, and evolving. It’s a dialogue between people in the present and an inheritance of texts and traditions and people can choose what of those texts and traditions they wish to emphasise.

So it’s not like religion is the equivalent of a radio station set with a dial and you can definitely find it. It’s a whole series of points on a bandwidth.

That understanding ought to give us hope, however long-term it may have to be. It certainly ought to contribute to a lessening of social prejudice and a promotion of constructive ways of addressing the problem of violent Islamic groups and individuals.

And obviously what a definition of an extremist is, what a radical is, will depend where you stand on that bandwidth. Because it cannot be emphasised enough that jihadists do not think of themselves as extremists. To them, it’s us, the comfortably secular and liberal kind of people . . . who are the extremists. Jihadists see themselves as models of righteous behaviour. They see themselves as doing God’s will as expressed in the pages of his holy book the Koran and the sayings of his prophet Muhammad. And they also see themselves as obedient to something else — to the example of Muhammad. The Koran is absolutely explicit about this. In the Messenger of God it says you have a beautiful example, an example to follow.

And so it does matter then, to jihadis no less than to the vast majority of Muslims who would never in a million years set about destroying the antiquities of the Near East, or taking sex slaves, or murdering those who mock the Prophet. But sanction for what they do is indeed to be found within the various biographies and traditions that are associated with the Prophet.

So what does Tom Holland see as the appropriate response? Continue reading “De-Radicalising Muhammad”

“What do the Charlie Hebdo murders and the rise of the Islamic State owe to Islam? It would be comforting to insist, as many have done, that they owe nothing at all; but Holland, in the inaugural Christopher Hitchens Lecture, argues that the truth is more complex. The best way to combat jihadism, he proposes, is to recognise the centrality of Muhammad to Islam – and that he comes in many forms. There is the moral leader who swallowed abuse peaceably; and there is the war leader who ordered people who insulted him put to death. How best, then, to de-radicalise the Prophet? Tom Holland is author of In The Shadow of the Sword, Rubicon, Persian Fire, Millenniumand the new translation of The Histories by Herodotus. Chaired by Katrin Bennhold of the New York Times.” — from the Hay Festival program.

Denouncing Islamic State as not representing “true Islam” is a well-intentioned declaration but counterproductive and seriously problematic, according to historian Tom Holland in the inaugural Christopher Hitchens Lecture at the May 2015 Hay Festival. The title of his talk is De-Radicalising Muhummad (available online).

What is wrong with these well-meaning efforts to defuse anti-Islamic tensions?

What it does is imply that there is a normative, authentic Islam, one that embodies ideals that are perfectly compatible with liberal, secular Britain, and then there are misinterpretations of it, distortions of it, that are not really Islam at all. . . . .

By denying the title of Muslims to Islamic State Western governments are actually playing the same lethal game as the Islamic State themselves. Because what the Islamic State do is to condemn other Muslims as either apostates or heretics — the better then to justify their elimination.

I really don’t think it is for Prime Ministers or Home Secretaries to play that game. Because once you take it on yourself to define what is or isn’t authentic Islam then you are buying into the notion that such a thing as authentic Islam actually exists.

Now if you’re a believer of course that’s fine. You will accept that indeed Islam was given to you by God and therefore it does have some absolute Platonic essence.

But if you’re not a believer then a religion is just like any other manifestation of human culture. It’s something that is porous, variable, forever mutating, and evolving. It’s a dialogue between people in the present and an inheritance of texts and traditions and people can choose what of those texts and traditions they wish to emphasise.

So it’s not like religion is the equivalent of a radio station set with a dial and you can definitely find it. It’s a whole series of points on a bandwidth.

That understanding ought to give us hope, however long-term it may have to be. It certainly ought to contribute to a lessening of social prejudice and a promotion of constructive ways of addressing the problem of violent Islamic groups and individuals.

And obviously what a definition of an extremist is, what a radical is, will depend where you stand on that bandwidth. Because it cannot be emphasised enough that jihadists do not think of themselves as extremists. To them, it’s us, the comfortably secular and liberal kind of people . . . who are the extremists. Jihadists see themselves as models of righteous behaviour. They see themselves as doing God’s will as expressed in the pages of his holy book the Koran and the sayings of his prophet Muhammad. And they also see themselves as obedient to something else — to the example of Muhammad. The Koran is absolutely explicit about this. In the Messenger of God it says you have a beautiful example, an example to follow.

And so it does matter then, to jihadis no less than to the vast majority of Muslims who would never in a million years set about destroying the antiquities of the Near East, or taking sex slaves, or murdering those who mock the Prophet. But sanction for what they do is indeed to be found within the various biographies and traditions that are associated with the Prophet.

So what does Tom Holland see as the appropriate response? Continue reading “De-Radicalising Muhammad”

Continuing from the previous post. . . .

Eyewitness accounts are not necessarily more reliable than other sources. Timothy Good compiled 100 eyewitness accounts of the assassination of President Lincoln and its immediate aftermath in We Saw Lincoln Shot: One Hundred Eyewitness Accounts. David Henige comments in Historical Evidence and Argument (2005):df

Reading these reminds us of the omnipresent Rashomon effect, and also that a secondary account that collects and evaluates a number of primary sources might actually be preferred to these, even when it paraphrases them, as long as it does this well, and as long as it allows access to all the evidence. (2005: 48 — Formatting and bolding mine in all quotations)

We have all heard of the studies that demonstrate the depressing unreliability of memories of events witnessed and experienced. Henige cites several articles addressing many of these studies and I attempted to follow up a few to flesh out details. One common theme is the way false memories can be implanted as a byproduct of others asking a witness questions that introduce the possibility of details that were not originally seen (e.g. Wells and Olson).

Here are a few pertinent sections from Toward a Psychology of Memory Accuracy by Goldsmith, Koriat and Pansky:

- Although thinking about a perceived event after it has happened helps maintain its visual details, thinking about imagined events also increases their vividness, and may therefore result in impaired reality monitoring for these events (Suengas & Johnson 1988). Goff & Roediger (1998) found that the more times subjects imagined an unperformed action, the more likely they were to recollect having performed it. . . . .

- The fact that people know at one time that a certain piece of information was imagined, dreamt, or fictional does not prevent them from later attributing it to reality (Durso & Johnson 1980, Finke et al 1988, Johnson et al 1984). . . . ;

- In comparing the results for an immediate test with those for a test given two days later, the proportion of accurate recall declined over time, whereas false recall actually tended to increase (McDermott 1996).

Nor does the research support the belief that false memories are necessarily the product of trauma and psychological repression:

Many cognitive psychologists, however, doubt these assertions (Lindsay 1998, Loftus et al 1994), pointing instead to evidence suggesting that false memories may arise from normal reconstructive memory processes.

Henige’s conclusion:

We can hardly re-enact the life experiences of eyewitnesses from the past to judge their capacity with respect to memory. The alternative is to conduct large-scale and repeated experiments that test various kinds of memory. As noted, hundreds of these have been carried out and in general the results have not been encouraging for any historians who might wish to believe eyewitnesses implicitly.

Testis unus, testis nullus, runs the Roman legal dictum: “one witness [is] no witness.”

Or as a less exalted source [Granger, Shades of Murder] put it: “Unsubstantiated? It means that no other person than yourself has claimed to have witnessed these things or been able to show that they existed.” — (2005: 49)

In ancient history scholars can find themselves depending more often than not single sources for what they know. One would expect this difficulty to make historians more cautious about how they interpret and rely on this solitary pieces of data for various arguments but unfortunately the opposite is found to be the case far too often.

There is a natural tendency to treat unique evidence with kid gloves.22 (2005: 49)

Henige’s footnote no. 22 brings us to a biblical scholar as a negative example:

22 Or even attempt to turn it to advantage, as R.N. Whybray does when he writes: “[t]o regard as useless for the historian’s purposes the only account of a nation’s history written by its own nationals is, to say the least, extraordinary.” Whybray, “What Do We Know,” 72.

Naturally an “only find” does deserve preservation. No-one disputes its importance. However,

that fact by itself should persuade the historian to apply every form of internal criticism possible. (2005: 49)

.

.

In my recent post Comparing the sources for Caesar and Jesus I referred to Historical Evidence and Argument (2005) by the historian David Henige. It contains an excellent chapter on the problems historians face with various kinds of source materials. It’s the sort of work not a few theologians who regard themselves as historians yet who have had little formal training in history beyond their field of biblical studies would do well to read. As for the rest of us, it can help clarify our understanding of the sources that lie behind the stories and arguments we read about the origins of Christianity.

In my recent post Comparing the sources for Caesar and Jesus I referred to Historical Evidence and Argument (2005) by the historian David Henige. It contains an excellent chapter on the problems historians face with various kinds of source materials. It’s the sort of work not a few theologians who regard themselves as historians yet who have had little formal training in history beyond their field of biblical studies would do well to read. As for the rest of us, it can help clarify our understanding of the sources that lie behind the stories and arguments we read about the origins of Christianity.

Sources are commonly said to fall into two types. (Henige discusses more than two but I focus here on the main ones.)

Confusion sometimes arises depending on whether the historian is referring to “absolute” or “relative” primary sources.

The latter approach [i.e. primary in the relative sense] allows considerably more latitude, perhaps too much, in that whichever sources we have that are — apparently — closest to the events we are interested in are duly termed “primary,” even though they might be separated by centuries from these events. By this way of thinking, historians would always have access to something called “primary” because each historian can define the term idiosyncratically. (Henige 2005: 43)

What is meant by primary in the “absolute” sense?

Leopold von Ranke, and before him John Lingard, held a more stringent view; only a source that was at least “contemporary” can justly be considered primary.1 This sounds reasonable and would help provide consistency . . . (pp. 43-44)

The footnote is to the following: Continue reading “Understanding Historical Sources: Primary, Secondary and Questions of Authenticity”

Previous posts in this series:

Earlier posts on Plato’s Laws

Plato’s and the Bible’s Laws and Ethics Compared (2012-09-14)

Plato’s template for the Bible (2012-09-16)

I’m passing over this section of Laws quickly, pointing to no more than a couple of details that meet biblical values.

Many works in the Bible teach that obedience to the law of God brings a blessed and happy life while the ways of sinners were plagued with misfortunes. Of course there are a few works that reassure us that not everyone was so naive (e.g. Job). Nonetheless, it’s a “good moral” that is taught to children and many churchgoers. It’s also the root of so much guilt that has inflicted many who have been taught that God heals the faithful.

Plato knew the reality of life but deemed it wise to teach a lie to keep people good. (Guilt and finger-pointing be damned.) Many know the “noble lie” principle from his Republic but he repeated it in Laws:

662b

[W]ere I a legislator, I should endeavor to compel the poets and all the citizens to speak in this sense; and I should impose all but the heaviest of penalties on anyone in the land who should declare that [662c] any wicked men lead pleasant lives, or that things profitable and lucrative are different from things just; and there are many other things contrary to what is now said . . . by the rest of mankind,—which I should persuade my citizens to proclaim.

Plato knew even the gods knew it was not really a rule that the happiest life is the just one . . . Continue reading “Plato’s Laws, Book 2, and Biblical Values”

When I started writing for Vridar, Neil pointed out that in one of my book references I had linked to a Google Books page. He said he preferred to use LibraryThing instead. I grumbled to myself, but dutifully created an account and complied with his request.

Eventually, I came to understand that he wasn’t making an arbitrary demand. Vridar doesn’t funnel people to Amazon hoping to collect a small fee. We don’t show ads — at least not deliberately. From LibraryThing, you can go to whichever online store you want. We don’t make that choice for you.

We’re not looking for Vridar generate income, even if it’s just to break even. Sometime back, when a certain fool nuked our blog and forced us to move to a different host, we deliberately chose a “dot-org” address to show that we mean business, or rather that we don’t mean business. We stand instead for the free and open flow of ideas.

But if that “free and open flow” means anything at all, then you need to know that we aren’t motivated by something else. You should know, for example, that we don’t take kickbacks for reviewing books or for linking to somebody else’s site. Nor will you ever see us block links to other biblioblogs, even when they routinely block us and assiduously pretend that we don’t exist. There are blogs out there whose moderators routinely delete or heavily edit Neil’s comments. We won’t do that here.

Recently, I received an email that was part of a PR campaign for celebrating 50th anniversary of the New International Version (NIV). This translation of the Bible began with a meeting of the Committee on Bible Translation (CBT) back in 1965. The lady who wrote the form letter encouraged us to share certain stories with our readers to help or enlighten them. Obviously, the PR firm who got our email addresses hadn’t read the countless times in posts wherein we’ve slammed the NIV as one of the worst English translations available, if you care about what the text actually says. She wrote: Continue reading “What Is Vridar?”