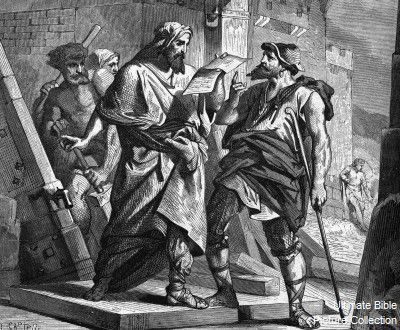

For a discussion of the old view of Israelite Kingship and comparison with today’s understanding:

Clines, David. 1975. “The Psalms and the King.” Theological Students’ Fellowship Bulletin 71: 1–6. (Reprinted in On the Way to the Postmodern: Old Testament Essays, 1967–1998, vol. 2 (Journal for the Study of the Old Testament Supplement Series, 293; Sheffield: Sheffield Academic Press, 1998), pp. 687-700.)

The last part of H. H. Rowley’s argument against the views of Joachim Jeremias and others that at least some Second Temple Judaeans held the notion of a Suffering Messiah relates to views that are no longer extant, as far as I am aware, among biblical scholars today. My understanding is that few today continue to hold to the idea that Israel’s kings participated in annual rituals of humiliation and rebirth as representatives of a dying and rising divinity.

If, as was once widely understood, the king of Israel or Judah regularly enacted such a ritual,

This evidence would seem to justify the inference that the concepts of the Davidic Messiah and of the Suffering Servant alike had their roots in the royal cultic rites, though they developed separate elements of those rites. (87)

That is, the separate concepts of Davidic Messiah and Suffering Servant developed their own pathways after the demise of the kingdom and during the periods of Babylonian captivity and Second Temple era.

Rowley next step (along with other scholars) is to posit that these two separate strands of ideology were united in the teachings of Jesus himself. Why with Jesus? Because

There has been no success in all the endeavours made to find previous or contemporary identification of the Messiah with the suffering servant of Yahweh. (87)

Rowley is citing H. Wheeler Robinson, whose complete statement follows:

It is no exaggeration to say that this is the most original and daring of all the characteristic features of the teaching of Jesus, and it led to the most important element in His work. There has been no success in all the endeavours made to find previous or contemporary identification of the Messiah with the suffering servant of Yahweh. The Targum of Jonathan for Isaiah liii. does give a Messianic application to some parts of the chapter, but, by a most artificial ingenuity, ascribes all the suffering to the people, not to its Messiah. This is very significant for the main line of tradition. There is no evidence of a suffering Messiah in previous or contemporary Judaism to explain the conception in the consciousness of Jesus. (Robinson, 199)

“Most original and daring”? Do I detect a confessional bias leading to the conclusion that Jesus owed nothing to distinctive or innovative to any earlier Jewish belief systems?

It seems so.

One may wonder if Rowley’s arguments against the general views of Jeremias and others are influenced by religious faith so that they become very exacting in demanding unambiguous and explicit statements testifying to a pre-Christian suffering messiah view; but one must also concede that the arguments of Jeremias rest most heavily on inference and one’s own assessments of probability.

Postscript: Another point I have not addressed in these posts is raised by critics other than Rowley against the idea of a pre-Christian suffering messiah. That is, making a clear distinction between “suffering” messiah and a “slain” messiah. In sifting through the evidence some scholars would insist that we be careful not to assume that a messiah who is killed is necessarily one who suffers as in experiencing the sorts of torments apparently suggested in Isaiah 53.

I titled this post, “concluding a case against”, not “the” case. If I begin to see that Morna Hooker has added further significant arguments against the views of Jeremias I will post those here, too.

Previous posts in this series:

And the series covering Jeremias’s case for a pre-Christian suffering/dying messiah:

Zimmerli & Jeremias: Servant of God (8 posts)

Robinson, H. Wheeler. 1942. Redemption and Revelation: In the Actuality of History. Library of Constructive Theology. London: Nisbet.

Rowley, H. H. 1952. The Servant of the Lord and Other Essays on the Old Testament. London: Lutterworth Press.