Before continuing with the scholarship that questions the traditional view that many of the Old Testament books were stitched together from much older texts, let’s lay out on the table a very broad overview of the thesis of a Dutch scholar, Jan-Wim Wesselius (I love his homepage photo and caption), as published in The Origin of the History of Israel: Herodotus’ Histories as Blueprint for the First Books of the Bible. (This was the most expensive book I had ever purchased in my entire life, so I continue to guard it well.)

Before continuing with the scholarship that questions the traditional view that many of the Old Testament books were stitched together from much older texts, let’s lay out on the table a very broad overview of the thesis of a Dutch scholar, Jan-Wim Wesselius (I love his homepage photo and caption), as published in The Origin of the History of Israel: Herodotus’ Histories as Blueprint for the First Books of the Bible. (This was the most expensive book I had ever purchased in my entire life, so I continue to guard it well.)

In this post I select just one detail that is not meant to persuade the sceptical (and scepticism is a virtue) but only to stimulate thoughts anew among anyone who has not traveled this road before. There is much more to be said along with the snippet of data I present here, and I have posted one of those snippets on vridar.info comparing Moses with Herodotus’ portrayal of the Persian king Xerxes (and the Plagues of Egypt with the catastrophes inflicting the army of Xerxes). A serious treatment comparing Herodotus’ Histories would need to start with a 1993 publication, The Relationship Between Herodotus’ History and Primary History by Mandell and Freedman. One of the more fascinating insights is that the Greek history is in many ways a “theological” history like the Bible’s historical books. The same lessons of the the role of the divine in and over human affairs are found like a unifying thread in both works. But such details are for another time.

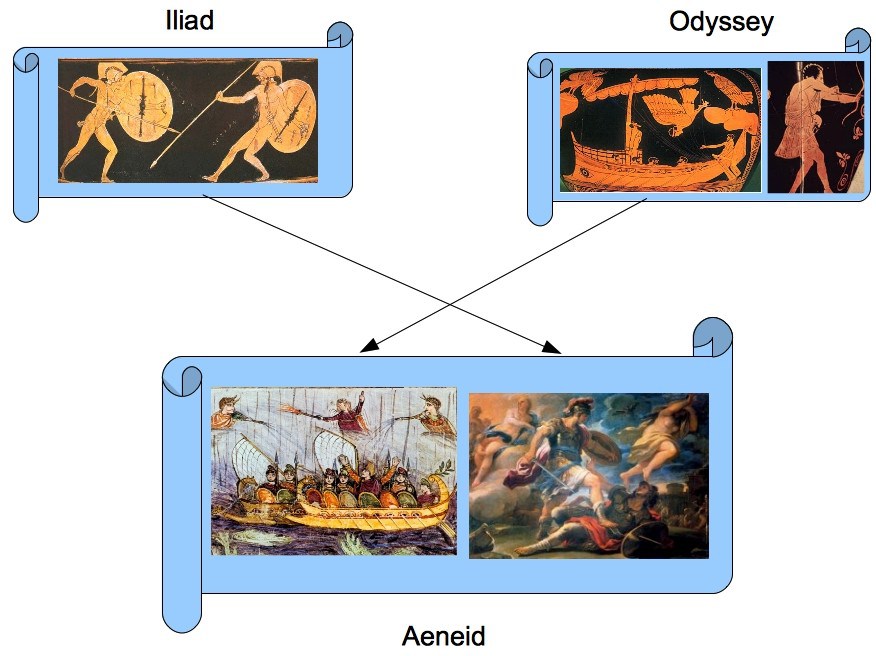

To appreciate what is to follow it would help to have some knowledge of both Homer’s epics, the Iliad and Odyssey, and Virgil’s epic poem of the founding of the Roman race, the Aeneid. G. N. Knauer sums up the way Virgil did not merely serendipitously draw upon recollections of what he had read in Homer’s epics, but he clearly studied the structures of Homer’s epics and built his own epic upon a reassembling of that structure, perhaps in an effort to surpass the artistry of the original.

. . . Vergil clearly realized how Homer conceived the structure of the Odyssey and . . . therefore did not simply imitate sporadic Homeric verses or scenes. On the contrary he first analysed the plan of the Odyssey, then transformed it and made it the base of his own poem.

What is especially significant is that this is one case-study of how ancient literature very often worked. Reworkings of earlier masters was a highly respected skill.

I don’t think I’m alone in also thinking Virgil reworked a single epic out of Homer’s dual effort. The Aeneid is an epic poem of the travels of Aeneas, founder of the Roman race, from the time he fled the conquered and burning Troy until the time he found a secure place in Italy after many battles with the local Latin tribes. The Roman epic begins with the adventures of a long voyage of Aeneas to his destined homeland — just as the second Homeric epic, the Odyssey, narrates the adventurous travels of the Greek hero. The second half of the Roman epic recounts many battles reminiscent of Homer’s first epic, the Iliad. Both conclude with the climactic death in battle of a warrior protagonist — Hector and Turnus. (Of course, the Odyssey likewise ends in much bloodshed, but this action is actually a small part in a larger narrative of deception, plotting and homecoming.) So a very broad comparison of the larger structures of these epics looks like this:

But there’s more. Much more. Knauf also writes (my formatting and emphasis):

In these [books] Aeneas is represented throughout as a hero surpassing his Greek counterpart, Odysseus, who had passed through the same or similar situations shortly before him (in epic time).

- Odysseus, the victor,

- destroys Ismaros in Thrace;

- Aeneas, the exile (3.11),

- founds Ainos in the same region.

- On his way home to the patris, Ithaca, west of the Peloponnesus, Odysseus is shipwrecked by a storm at Cape Maeiea

- Aeneas, in spite of a storm, successfully passes this cape (cf. 5. 193) on his way to the west, where in the end he will find the promised patria, Hesperia.

Here for the first time one begins to sense Vergil’s purpose in following Homer.

Let’s return Knauf’s observations on the imitation and rearrangement of the structure:

The complete structure of the Homeric epics, not simply occasional quotations, was no doubt the basis for Vergil’s poem. I cannot explain these findings otherwise than by the suggestion that Vergil must have intensively studied the structure of the Homeric epics before he drafted in prose his famous first plan for the whole Aeneid.

It seems clear that Aeneas, who excelled Odysseus in the first part of the Aeneid, now surpasses the Greeks who had been victorious in Troy. [. . .] The way in which he completes the divine mission to found a new Troy, that is Rome, elevates him morally far above the Greek heroes.

And this brings back to mind Marianne Palmer Bonz’s far too under-rated study, The Past As Legacy: Luke-Acts and Ancient Epic. Her thesis that the story of Acts, in particular Paul’s voyage to Rome to found what was to become, in effect, a “new Jerusalem”, was an emulation of the founding of worldly Rome by Aeneas. I have groped in earlier posts (some years ago) to address more detailed evidence for this thesis. But I think the final word is still to be written on this. (I would dearly love to discuss this book with its author, Bonz, especially with a view to covering details I suspect could strengthen her case, but have not had any success in finding an email contact.)

And this brings back to mind Marianne Palmer Bonz’s far too under-rated study, The Past As Legacy: Luke-Acts and Ancient Epic. Her thesis that the story of Acts, in particular Paul’s voyage to Rome to found what was to become, in effect, a “new Jerusalem”, was an emulation of the founding of worldly Rome by Aeneas. I have groped in earlier posts (some years ago) to address more detailed evidence for this thesis. But I think the final word is still to be written on this. (I would dearly love to discuss this book with its author, Bonz, especially with a view to covering details I suspect could strengthen her case, but have not had any success in finding an email contact.)

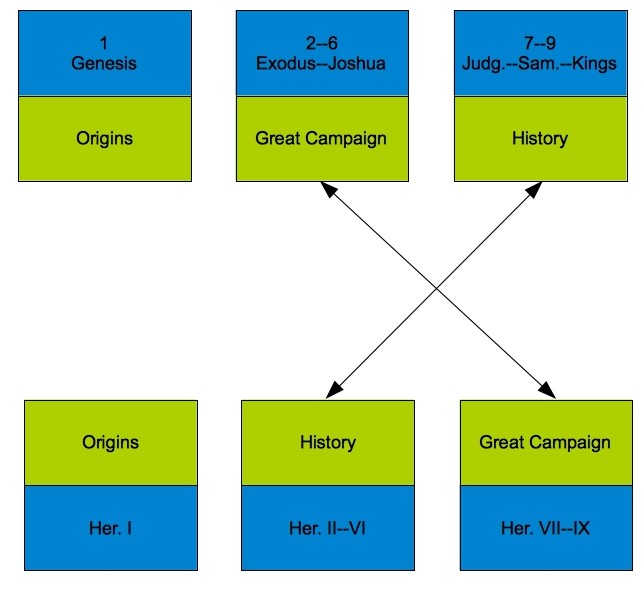

So after all these digressions (humour me, it’s Friday night here and my glass of wine companion is telling me to stay put and finish this thing), let’s return to the broad structural comparisons between the Histories of Herodotus and the Primary History (Genesis to 2 Kings) of the Bible. Here is what we find. Another graphic will say it all, and here we return to Jan-Wim Wesselius and The Origin of the History of Israel:

Origins represents mythical history — Adam and Eve, Paris and the golden apple trick to win the beautiful woman; the Great Campaign represents the Exodus to the conquest of Canaan on the one hand, and the departing Asia via the Hellespont to conquer Greece on the other.

There is much more to this broad structure when we bring in the microscope and find the narratives of the biblical patriarchs, Terah-Abraham-Isaac-Jacob-Joseph . . . . Moses, uncannily matching aspects of Phraortes (like Terah he died before completing his mission), Cyaxares (like Abraham fulfilled his mission, Astyages, Mandane, and Cyrus (who, like Joseph, attained to mastery over the foreign land) . . . . and finally to Xerxes who, like Moses, through a most marvellous feat crossed a sea with a great army to conquer a new land.

Then there are the geographical resonances: the first patriarch’s live out their history between Canaan and Egypt as those in Herodotus’ Histories do between Media and Lydia; Joseph leaves Canaan to rule Egypt as Cyrus leaves Media to rule Lydia; Moses leaves Egypt to conquer Canaan as Xerxes leaves Lydia to conquer Greece. And that is just touching the ribbon around the wrapper.

There’s a lot more where all this comes from. Stay tuned. I hope to share it all before I die. (Unless them scholars decide to share their research with you all first — like they should!)

If you enjoyed this post, please consider donating to Vridar. Thanks!

Don’t forget Flemming Nielsen, The Tragedy in History: Herodotus and the Deuteronomistic History (Sheffield 1997)

Russell Gmirkin, Berossus and Genesis, Manetho and Exodus (London 2006)

and not least

Philippe Wajdenbaum, Argonauts of the Desert (London 2011)

It is moving very fast now.

Wajdenbaum I began posting on in detail last year and am about to resume those posts again. Thanks for the other cites.

Theres an interesting youtube series about Homer and the gospels – http://www.youtube.com/playlist?list=PL1D58C69D194384D2&feature=plcp. I thought id share.

Can you tell us in which video the discussion about Homer begins? Video 1 did not mention it. Video 2 (http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=msZ5X3uyeeA&feature=relmfu) contained one of the best discussions I’ve seen establishing the inauthenticity of the verses in Mark after 16:8 — but no mention of Homer.

—–www.youtube.com/watch?v=tTJT67kgsfc&list=PL1D58C69D194384D2&index=5&feature=plpp_video

Did Mark write his “gospel” as a fictional tale? An allegory of the heavenly Jesus “pwning” the Jews for rejecting him? Did Mark rely upon Greek mythology to help him sculpt his own mini-epic? This vid is the start of evidence intended to answer this question…. beyond a reasonable doubt.

The Homer/Mark information I present in this series comes from an amazing book, “The Homeric Epics and the Gospel of Mark” by Dennis R. MacDonald.

Part 4 of the series poses the question, and it is Part 5 where the detailed exploration of the idea begins:

—www.youtube.com/watch?v=tTJT67kgsfc&feature=autoplay&list=PL1D58C69D194384D2&playne

For some reason link went to beginning of series.

I hope this goes straight to the parallels between Mak and Homer:

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=NZIjDZGMZes

Neil, I hope you return to Wesselius soon. We need a more rigorous overview of his ideas and research.