In this post I will explain “my personal reason” for strongly suspecting a Hellenistic origin of the biblical literature — though I am sure I have come across the same ideas throughout different books and articles over the years. It follows on from #5 in the preceding post. When I wrote that I was expecting to follow up with detailed discussions from interpretations of the archaeological finds but have decided now to put that off for later.

The reason I feel a particular “vibe” with the Hellenistic era origin of the first Bible texts is “the nature of the biblical literature itself.” (These thoughts follow on from my point 5 in the preceding post. — They were also written before The Problem with an Early Date for the Hebrew Bible which is a more developed argument, or approaches it from a slightly different slant. Passages in square brackets are revisions to my original post on another forum.)

—o0o—

My “personal vibe” that is in sync with the Hellenistic era is reflection on “the nature of the biblical literature itself”. The Primary History (Genesis to 2 Kings) is not the kind of literature that arises sui generis from a vacuum. One expects to see antecedents over time that lead to that kind of work. And the closest antecedents we find are in the Greek literature, not in that of the Syria-Mesopotamian regions. Assyrian vassal treaties, the epics of Gilgamesh, of Baal, and so forth, simply fall short by comparison.

But what kind of society produces that kind of literature? It takes more than a scribal elite responsible for administrative and trade records, or even engaged in cultic verses and prayers and spells for cures, etc. The kind of literature in our Bibles required reasonably prosperous and complex societies with a literate class that engaged with the kinds of stories and ideas that had relevance to their class, ethnic and regional identities. They had to have a reasonably widespread audience to engage with those ideas and stories and whose interest or vulnerabilities or needs encouraged their literary development. The social groups must have been somewhat extensive and complex because of the various competing and related ideas found in that literature.

In other words we are talking about fairly advanced societies in economic growth and social complexity, and who also have comparable antecedent literature.

The archaeological record does point to some kind of growth of Jerusalem and surrounds in the eighth and seventh centuries after the fall of Samaria to the Assyrian army, but [Finkelstein and Silberman are unable to point to any archaeological evidence pointing to political-social-economic revival in Josiah’s time]. Besides, what kinds of antecedents were available at or up to that time to mushroom into what we find in the Bible?

The Persian era in Judea is by all accounts that I have seen one of relative decline. Persian “liberal” rule that allowed Judeans and Samarians to “do their own thing” is more easily understood as administrative neglect, not caring at all about their development — only collecting levees for the army and taxes for the king. (Witness the Xenophon’s ability to march his Greek army untouched through the empire!)

The economic revival, with its related social growth in complexity and size, came with the arrival of the Greeks. So did the antecedent literature.

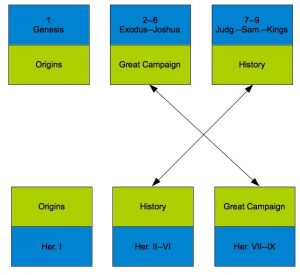

Herodotus’s Histories has a remarkably similar structure to the Primary History (Genesis to 2 Kings): opening with world history, having a close look at Egypt as a follow up, and finally getting down to the narrow view of the conflict between two powers — AND all told within the framework of a theological interest: the lesson of the deciding hand of the god through his earthly sanctuary. And all told in a series of books in prose, both frequently with competing accounts of the same event.

Mandell, Sara, and David Noel Freedman. The Relationship Between Herodotus’ History and Primary History. Atlanta, Ga: University of South Florida, 1993. (Primary History = Genesis to 2 Kings. Note that Mandell and Freedman were not suggesting the Primary History originated in Hellenistic times — though at the moment I do!)

This diagram is derived from another study comparing the two works, one by Wesselius: [this box section was not part of the original post] |

I am not denying the obvious differences when saying that. What I’m trying to do is to draw attention to the “equally obvious” similarities. Did those similarities really emerge independently? Did the Hebrew literature really inspire that of the Greeks? Were the Judeans and Samarians in the poverty-stricken, underdeveloped Persian era really hosting a literate class devouring Greek literature? . . . .

And then we have the ideological content of the literature. How do we explain the sudden introduction of stories of Exodus, Joshua’s Conquest, Judges, David and Solomon’s united kingdom and empire, if those — as the archaeological record tells us — never happened? [Finkelstein and Silberman explain the purpose for composing Deuteronomy and the Primary History of Israel was for King Josiah to unite his people and propagandize them into supporting his hopes for expansion to the north where the northern kingdom of Israel had been crushed by the Assyrians. But it is difficult to see how such a program explains so much of the content of those books, especially the ethical codes for social welfare relating to slaves, women and the poor.]

At this point it is worth looking at the propaganda use the biblical works were put to in the Hasmonean period. Were not the Hasmoneans seeking to justify their conquests by appeals to a historical heritage? In a time of Greek conquest do we not expect indigenous populations to seek redress by counter-narratives that place themselves in positions that challenge or make themselves equal to the great powers? These are more than rhetorical questions.

As for the divisions found even within the literature — [Jerusalem is not always depicted as the obvious choice for God’s temple; sometimes we find indications that a Samaritan/Mount Gerizim point of view dominates] — have not scholars long since identified these differences underlying the multiple points of view (and sometimes outright conflict) within the biblical literature?

I posted my observations of the striking similarities between Plato’s Laws and the Pentateuch in a series of posts back in 2015:

- Plato’s and the Bible’s Ideal Laws: Similarities 1:631-637

- Plato’s and Bible’s Laws: Similarities, completing Book 1 of Laws

- Plato’s Laws, Book 2, and Biblical Values

- Plato and the Bible on the Origins of Civilization

- Bible’s Presentation of Law as a Model of Plato’s Ideal

- Plato’s and the Bible’s Ideal States

- Plato’s Thought World and the Bible

Of course Russell Gmirkin has explored these and other similarities exhaustively.

[After reading Argonauts of the Desert by Philippe Wajdenbaum] I was prompted to read Plato’s Laws (as well as, again, Timaeus and Crito) and was completely thrown back in my chair when I saw (and wondered how I had not seen it before) the striking similarities between Plato and the Pentateuch’s law-giving narrative. Of course all those sacrifices and cultic rituals are of Levantine/Syrian/Canaanite origin, but the Pentateuch is a lot more than cultic regulations forbidding to seethe a kid in its mother’s milk.

The creation, the merging of humans and gods, the flood and annihilation, the wandering of the new generation, the coming together ….. and so forth. And then the laws about holiness, godliness, sacred feasts, marriage and sexuality, the judges and tribes, etc etc etc etc : Did Plato really twig to all of that from his reading of the Pentateuch? (One scholar has addressed the relationship of a scene in Plato’s Symposium with the temptation of Adam and Eve in the Garden of Eden and others have suggested that the Hebrew work had an influence on the form of Herodotus’s Histories.)

And further yet — there are strong similarities between the biblical Yahweh and the Greek Dionysus [see, for example, Amzallag]. I have read the comparisons a number of times. Surely pre-Hellenistic Yahwism was distinctively Levantine, with no appreciable differences between the Yahwism of Samaria, Judea, Negev, Canaan, Syria…. So what gave him the Greek overlay in the Bible? [A caveat I should have added here: the Greeks did understand Dionysus to be a foreign god from the east.]

These are my generally subjective responses to how I read the literature of the OT with my knowledge of Greek literature in mind. I have not presented a systematic argument. But for what it’s worth, I thought it might be of some point to note how I have come to read the literatures of the Hebrews and Greeks and the conclusions that seem to present themselves prima facie to me as a result.

All posts in this series are archived at Dating Biblical Texts

If you enjoyed this post, please consider donating to Vridar. Thanks!

Finkelstein’s archeological research showed that Jerusalem was all but deserted [except the the Temple area] the whole time the Persians were in change. Jerusalem only began to be repopulated after Alexander the Great threw the Persians out.

In my reading, the Old Testament (OT) books span several ancient centuries, from the Sumerian, Egyptian, Assyrian, Babylonian, and Persian Empires, before the Hellenistic period.

Yet the Hellenistic period was more literate than any previous period, so up to half of the OT may have been written in the OT period. (This includes the Book of Daniel, which pretends to be from the Babylonian period). Yet a substantial amount of the OT was written during the start of the Second Temple period (ca. 550 BCE to 330 BCE).

I speak here of the books about the return of the Jewish aristocracy from Babylon captivity (ca. 607 BCE) until the conquest of Babylon by Persia (ca. 535 BCE). This is commemorated in Isaiah 45. It is also the theme of Ezekiel, Ezra and Nehemiah.

Persia was a great friend to Israel, liberating the captive Jews from Babylon and helping the Jews build the Second Temple. (Actually, the Persians helped all of their allies rebuild Temples destroyed by the Babylonians.)

The Farsee religion of Zarathustra had two main deities: the Good God had angels in Heaven and the Evil God had demons in Hell, competing for the souls of humans. At the End of Time there would be a Global Resurrection, a Last Judgment, sending the good to heaven and the wicked to hell.

Some Jewish priests were so grateful to the Persians that they formed a new sect that adopted the doctrine of Resurrection — the Pharisee (Farsee) sect. The doctrine of Resurrection was not found in the Torah, and it is not found in Hellenist literature. It comes from the Persian (Second Temple) period.

As late as the 1st century, non-Pharisee sects would not accept the Persian doctrine, as described in ACTS 23:6-7.

But what do we do with the absence of any independent (archaeological) evidence for the narrative about a Persian era rebuilding of a Jerusalem temple?

The posts I have been publishing recently owe their origin to the time I first read Philip R. Davies’ 1992 book, In Search of Ancient Israel.

I have been thinking the same things recently. The literary genres and devices used in Genesis, in my opinion, are utterly Greek. The more I read both OT literature and Greek literature, the more I am inclined to believe OT literature is satire for the purpose of societal reform or anti-Hellene propaganda, etc. It truly has no parallels in ancient Mesopotamian writings.