Derek Lambert of the MythVision program dedicated a program to something he found on “yours truly” blog outlining aspects of Philippe Wajdenbaum’s case for linking Abraham’s (near) sacrifice of Isaac with the Greek myth of Phrixus:

- The Bible’s roots in Greek mythology and classical authors: Isaac and Phrixus

- Greek Myths Related to Tales of Abraham, Isaac, Moses and the Promised Land

Standard definitions

Myths are prose narratives which, in the society in which they are told, are considered to be truthful accounts of what happened in the remote past. They are accepted on faith; they are taught to be believed; and they can be cited as authority in answer to ignorance, doubt, or disbelief. Myths are the embodiment of dogma; they are usually sacred; and they are often associated with theology and ritual. Their main characters are not usually human beings, but they often have human attributes; they are animals, deities, or culture heroes, whose actions are set in an earlier world, when the earth was different from what it is today, or in another world such as the sky or underworld. . . .

Legends are prose narratives which, like myths, are regarded as true by the narrator and his audience, but they are set in a period considered less remote, when the world was much as it is today. Legends are more often secular than sacred, and their principal characters are human. They tell of migrations, wars and victories, deeds of past heroes, chiefs, and kings, and succession in ruling dynasties. In this they are often the counterpart in verbal tradition of written history . . .

Folktales are prose narratives which are regarded as fiction. They are not considered as dogma or history, they may or may not have happened, and they are not to be taken seriously. . . .

Bascom, William. “The Forms of Folklore: Prose Narratives.” The Journal of American Folklore 78, no. 307 (January 1965): 3. https://doi.org/10.2307/538099. p.4

At the time I wrote those blog posts I was struggling to understand how to apply a Lévi-Straussian structural analysis to the myths related to Phrixus as well as to the Genesis narrative of Abraham and Isaac, and I still am. I feel somewhat vindicated in my failure, though, by an Alan Dundes article —

- Dundes, Alan. “Binary Opposition in Myth: The Propp/Lévi-Strauss Debate in Retrospect.” Western Folklore 56, no. 1 (1997): 39–50. https://doi.org/10.2307/1500385.

— which notes that Lévi-Strauss fails to acknowledge the “standard genre definitions of myth, folktale and legend”. This failure may be more than a technical one since Lévi-Strauss insists that all variants or adaptations of a myth are essentially the “same myth” — not “legend” or “folklore”, given that myths (in his understanding) are told in a different linguistic/psychological registers from other kinds of narratives. So, if we follow Claude Lévi-Strauss’s reasoning, how could a biblical drama with more in common with a folktale or a legend be an adaptation of a myth?

Further, Levi-Strauss explained variants of myths among different tribes in South America as the product of different social customs and structures. One example:

Finally, we can note one striking inversion: in [Myth 7], the eggs were changed into stones; in [Myth 12], a stone is changed into an egg. The structure of the Sherente myth (M12), therefore, contrasts with that of the other versions — a fact that is perhaps to be explained in part by the social structure of the Sherente which, as we have seen, differs sharply from that of the other Ge tribes. (The Raw and the Cooked, p. 77)

In 2011 I failed to identify that kind of explanation for the differences between the Greek myth of Phrixus and the Genesis “Akedah” (the binding of Isaac). Since then, I have read Russell Gmirkin’s studies of the possible influence of Plato’s thought in his Laws on the Pentateuch. Wajdenbaum had addressed this notion earlier but Gmirkin’s work seemed (to me, at least) to strengthen that likelihood. I have now given up attempting a Lévi-Straussian explanation for the biblical account and have fallen back on a “Platonic” adaptation of the Phrixus myth.

If Lévi-Straussian approaches cannot explain how this biblical episode emerged out of a Greek myth, can an interest in applying Plato’s ideals succeed?

In the following I use the word “myth” in Plato’s simpler sense of a mere fabrication.

–o0o–

If the idea that Plato’s thoughts underlie much of the Pentateuch seems preposterous to you, I invite you to have a look through the earlier discussions relating to this question:

- In Search of Ancient Israel

- The “Late” Origins of Judaism – The Archaeological Evidence

- Various posts on the Documentary Hypothesis along with ….

- Plato and the Hebrew Bible (Gmirkin)

- Plato and the Biblical Creation Accounts (Gmirkin)

In nuce, the starting point for this post is the hypothesis that early in the Hellenistic era (third century B.C.E.), the priestly and scribal litterati of Samaria and Judea, possibly in close working relationship with the resources in Egypt’s Great Library of Alexandria, created the “historical” narratives that were to become the foundational literature of a new ethnic and cultural identity. The raw materials that these elites reshaped were the stories they had inherited from their home regions (Canaan, Syria, the Levant) along with new Greek epic, poetry, drama, historiography and philosophical writings. Guided by the ideals they imbibed from Plato, they aimed to construct new “foundation myths” that surpassed the ethics of their Greek overlords and thus asserted the superiority of their regional Yahwism over Hellenism. If Hellenistic culture can be defined as a blending of Greek and Asian ideas and expressions, the Pentateuch became a Hellenistic document par excellence — ironically, given that it was the ideological document that underlay subsequent Judean resistance against the Hellenistic rule of the Seleucids. Think of the regular experience of the colonized embracing the culture of their conquerors and using it against them.

My aim here is to try to explain how the Greek myth of Phrixus could have been transformed into the biblical narrative about the binding of Isaac.

–o0o–

For the points affirmed here about Plato’s program for the creation of a myth of origins for a new colony, see:

- Plato’s and the Bible’s Ideal Laws: Similarities 1:631-637

- Plato’s Laws, Book 2, and Biblical Values

- Bible’s Presentation of Law as a Model of Plato’s Ideal

and

As is well-known, Plato had no time for the follies of deities and humans in the Greek myths. Gods should always be presented as epitomes of the highest morality and heroes as ideal exemplars of god-fearing thought and behaviour. Plato further argued the ideal target audiences of such myths should be a heterogenous population settled from various regions into a new collective. (Should we note in this context the diverse “records” of the twelve tribes of Israel hailing from diverse places — Mesopotomia, Egypt, Canaan?) The myth should assure a people that their ancestral origins were both divinely guided and true. Although the first generation would naturally resist such notions the succeeding generation would be less prone to resist the new teaching.

Plato wrote that ideal laws and the mythical tales in which they were embedded should inculcate the most honourable fear of all, the fear of God, or utmost reverence.

Now let’s refresh our memories of the highlights of the myth of Phrixus and reflect on the possibility of their “Platonic foils”.

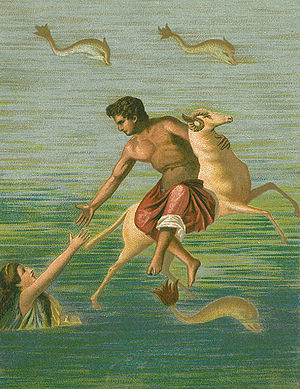

1. The king of Boeotia, Athamas, married a cloud goddess with whom he fathered twins: Phrixus and Helle. That cloud goddess, whose name was Nephele, was in fact a special creation by Zeus to look exactly like his wife Hera so she could deceive “a drunken, degenerate king” (Ixion) to goad him into punishment for behaving inappropriately towards Hera. That was before she married Athamas.

2. Athamas, frustrated with his superior wife’s haughtiness, rejected her and married instead the mortal Ino.

Immediately we can sense Plato’s displeasure. How much more noble to have a hero in a stable marriage, if not to a goddess at least to a woman who even in her old age was the desire of kings! Even better if her name can sound like “Princess”. Certainly not a “hero” married to a cloud that was created for the purpose of deception!

3. The second wife of Athamas (Ino) rejected her stepchildren so plotted to have them removed so that her own child could inherit the kingdom. The first step in her plan was to secretly parch the seed that was necessary to feed his people. Athamas was at his wits end not knowing how to overcome the “natural” calamity.

We can see core motifs here that may have been adapted into the Genesis narrative: Sarah rejecting the first born of Abram whose mother had been the slave (not a goddess), and forcing its departure from her household. Of course there is also the theme of barrenness transplanted from the ground to the persons of Sarah and Abram. In this context it is of interest to note that the earlier Hittite myth from which the Greek tale appears to have been borrowed spoke of barren land as well as animals failing to reproduce and even humans unable to have children.

Therefore barley and wheat no longer ripen. Cattle, sheep, and humans no longer become pregnant. And those already pregnant cannot give birth. (Hittite Myths, p. 15)

But in the biblical account the barrenness is not part of a wicked human plot (or in the Hittite myth the consequence of a god deserting his responsibilities in a childish pique) but appears as a condition that God is using to prove that the child to be born is not a natural offspring but a genuine divine gift. That’s another detail that a pure “Platonic” mind would find most fitting.

4. Athamas sought the advice of the god Apollo but Ino bribed his messengers to lie and report to the king that the god wanted him to sacrifice his first born son, Phrixus.

A human sacrifice prompted by a devious lie? Most emphatically utterly inconceivable in Plato’s world!

By now one might wonder why a “biblical” author might select such an unpromising myth as raw material to begin with. The answer to that question was set out in my earlier post, Greek Myths Related to Tales of Abraham, Isaac, Moses and the Promised Land. As in the larger biblical narrative, the episode of a would-be human sacrifice called off by last-minute divine intervention and the sudden introduction of a sheep (“out of nowhere”) was a prelude to a grander narrative of national inheritance and deliverance.

But let’s continue.

As noted above, Plato believed that an ideal community needed to value above all the fear of God. Abram, renamed Abraham, is a perfect demonstration of such a fear and reverence by his willingness to sacrifice his son in response to the divine command. Different versions of the Phrixus myth paint Athamas in a contrary light. In one early version of the myth he is driven mad and it is in that mental state that he carries out the sacrifice.

Fear of God is only commendable, of course, if God himself is perfect. Hence in the story world of the Bible God was in his perfection only testing the perfection of Abraham while simultaneously in his perfection keeping his promise that Isaac would be Abraham’s heir and progenitor of vast multitudes and kings. A modern psychotherapist might have a different evaluation of both God’s and Abraham’s characters but we have to adhere to the “story as told”.

5. Either Zeus or Nephele sent a golden winged ram to rescue Phrixus at the last moment by carrying him away.

In Genesis we read instead of a rational dialogue between Abraham and the divine agent and the “natural” appearance of a ram caught in a thicket nearby to be sacrificed as a substitute. We are removed here from the “far distant other world” of flying and talking golden sheep. On the contrary, we are in the “present world” and in “narrative historical time” that will be linked by named generations to the founding of the nation of Israel. Plato insisted that the myth had to be historically believable.

6. Phrixus sacrificed the ram as a thanksgiving offering for his rescue and hung its golden fleece on a tree. From there it was known as a token to bestow abundantly prosperous kingship to its possessor.

In the earlier Hittite versions what was hung in the tree branch was sheepskin containing tokens of natural abundance and prosperity.

Before Telipinu [son of the Storm God whose disappearance and return were marked by barrenness and plenty respectively] there stands an eyan-tree (or pole). From the eyan is suspended a hunting bag (made from the skin) of a sheep. In (the bag) lies Sheep Fat. In it lie (symbols of) Animal Fecundity and Wine. In it lie (symbols of) Cattle and Sheep. In it lie Longevity and Progeny. (Hittite Myths, p. 18)

The sheep caught in the thicket in the Abraham and Isaac tale appears when the God announces his great promise to Abraham and his son:

Abraham looked up and there in a thicket he saw a ram caught by its horns. He went over and took the ram and sacrificed it as a burnt offering instead of his son. So Abraham called that place The Lord Will Provide. . . . The angel of the Lord called to Abraham from heaven a second time and said, “I swear by myself, declares the Lord, that because you have done this and have not withheld your son, your only son, I will surely bless you and make your descendants as numerous as the stars in the sky and as the sand on the seashore. Your descendants will take possession of the cities of their enemies, and through your offspring all nations on earth will be blessed . . . (Genesis 22:13-18)

One other detail I bypassed here is the death of Phrixus’s sibling, Helle, who was said to have also been carried away by the flying sheep only to fall off its back and drown in the sea below (the Hellespont). If there is any relevance here it may be tied to the rejection of the other son of Abraham, Ishmael. But that is only an incidental and a most tentative observation. The theme of deities choosing a younger progeny to be an heir over an older one was known in Canaanite mythology long before biblical times.

It may be that the original form of the myth related to the literal sacrifice of a king — or of a child sacrifice by the king — who was deemed to be losing his power to sustain the abundance of the natural order. If so, that does not appear to be related to the Genesis episode — unless the Judean and Samaritan authors did have genuine historical memories of such a human sacrifice.

Leaving that possibility aside, I suggest that the above comparative interpretation of the Biblical mini-saga yields for us an explanation for how it might have been crafted from a Greek myth by a scribe guided by Plato’s ideals.

Bascom, William. “The Forms of Folklore: Prose Narratives.” The Journal of American Folklore 78, no. 307 (January 1965): 3. https://doi.org/10.2307/538099

Dundes, Alan. “Binary Opposition in Myth: The Propp/Lévi-Strauss Debate in Retrospect.” Western Folklore 56, no. 1 (1997): 39–50. https://doi.org/10.2307/1500385.

Hoffner, Harry A., and Gary M. Beckman, eds. Hittite Myths. 2nd ed. Writings from the Ancient World, no 2. Atlanta, GA: Scholars Press, 1998.

Levi-Strauss, Claude. The Raw and the Cooked. Translated by John Weightman and Doreen Weightman. New York: Harper & Row, 1969.