How and when did Christianity begin?

By “independent evidence” I mean sources that refer to the letters other than the letters themselves, such as the Church Fathers Irenaeus and Tertullian of the late second century. If we rely on the letters themselves we might choose to date them by their reference to a ruler of Damascus of uncertain date, most likely first century, and to Paul’s contacts with the original apostles of Jesus. The NT Acts of the Apostles (dated anywhere between the later part of the first century and first half of the second) contains a narrative of Paul’s life but provides no explicit indication that Paul wrote any letters. Scholars have remarked that Acts and the Letters present contradictory impressions of Paul’s beliefs.

We have the New Testament letters of Paul and other apostles. But there is no independent confirmation that these letters existed before the middle of the second century. All the independent evidence points to them being first known among a group of Christians (followers of Marcion) around the 130s or 140s CE. There is no independent evidence that places them any earlier. I recently reviewed and discussed the contents of a new book by Professor Nina Livesey arguing that Paul’s letters originated in a “school of Marcion” around the 130s/140s CE.

We have the four canonical gospels, but again, independent witnesses do not offer us any reason to believe that these existed before the middle of the second century of our era. There are references to Christians in works of historians Josephus and Tacitus but they are either of debatable authenticity or can tell us no more than what was being said in the second century.

We also have what has long been the unfortunately bypassed elephant in the room: How on earth did so many Christian groups arise declaring that Jesus had never been human, some saying he was never even crucified, some proclaiming that his own disciples remained ignorant of what he taught and preached falsehoods, some saying that Jesus came to abolish the law and others saying he came to keep the law more completely, some even saying he called the God of the Jews some kind of devil. None of that makes any sense if Jesus had gathered and inspired followers to proclaim his teachings after his death as the New Testament claims. I can understand modifications to his teachings arising as new situations arose, but not the wholesale divergence of whether he was even human, or whether he worshiped or denounced the God who created the world and gave the law, or whether his immediate disciples spoke truth or lies.

How could such wildly divergent ideas about Jesus have arisen from one of supposedly a number of teachers and prophets attracting followers in first century Palestine?

But what if it all happened the other way around?

What if there first appeared on the scene teachers denouncing the god of the Jews and proclaiming a new and higher god who offered salvation for those who had been led to death and destruction by the God of the Jewish Bible?

Could such a teaching be understood to have arisen in historical times either among Jews themselves or among their would-be friends who happened to be well informed about the Jewish Scriptures?

There shall be a time of trouble, such as never has been . . .

I think it can. Indications are that teachers of this kind (declaring the creator God of Genesis and the lawgiver God of Moses to be inferior deities to a higher, hitherto unknown, God who saves rather than kills) arose in the early decades of the second century. That was a time of

- some of the most horrific destructions wreaked by Jews (or Judeans of the time) on pagan temples and on Roman armies

- some of the most horrific mass slaughters of Jews, along with non-Jews, under the emperors Trajan and Hadrian

For some details of the uprisings of the Jews and their consequences in the time of Trajan, see

Why did a transnational revolt, with the Jews at its centre, erupt in 116, capable of seriously challenging the Roman empire, which at that very moment had reached the phase of its greatest expansion? . . . What events, in 115 and then 116 CE, first led to Greek-Jewish clashes in Mediterranean cities, and then caused the Jews to take up arms to destroy every element of pagan culture and religion they encountered in their path? — Livia Capponi: Il Mistero Del Tempio p.18 — translation

Thus nearly the whole of Judaea was made desolate . . . Many Romans, moreover, perished in this war. Therefore Hadrian in writing to the senate did not employ the opening phrase commonly affected by the emperors, “If you and your children are in health, it is well; I and the legions are in health.” — Cassius Dio, 69,14)

For the scale of destruction (of both Jews and Romans) in the Bar Kochba war in the time of Hadrian, see

The bloodshed of these times was on a scale that the war of 66-70 CE never approached. The destruction of the temple primarily involved the destruction of a city. The uprisings and their genocidal consequences in the second century were on a totally different scale.

Such times help to explain the emergence of the devaluation of the defining markers of Jewishness. As Nina Livesey writes,

Events leading up to and following the Bar Kokhba revolt can be understood as influential to the development of Pauline letters. For, the Bar Kokhba period saw not only massive destruction, death, and the removal of the Jewish population from Judaea but also the call for a ban on circumcision and the destruction of Hebrew scriptures? Rulings against the Jewish practice of circumcision and Jewish writings redound in discussions of these themes in texts dated in and around this period. In addition, treatments of Jewish law and circumcision in biblical and non-biblical texts dated to this period reveal a dramatic downward shift in their value. Comparably dismissive and/or derogatory assessments of circumcision and Jewish law do not surface in texts dated prior to the end of the first century. Discussions of the rite of circumcision dated at or after the Bar Kokhba revolt parallel those found in Pauline letters. (Livesey, 202f)

I think we can extend the point beyond the Bar Kochba war and the letters of Paul. The troubles began in the 110s and earliest indicators of teachers denouncing the Jewish Scriptures and their creator-lawgiver deity come from the same period.

The Dialogue, which was probably written shortly before the death of Justin (around 165 CE) (Lohr, 433)

Some historians believe that Book 2 was written during a persecution, that is, under Marcus Aurelius (161-80), because in 2.22.2 Irenaeus writes of persecutions of the just as if they are then going on. Books 1 and 2, then, may have been written before 180. (Unger/Dillon, 4)

Our information is scarce, vague and late, so we can only attempt a bare outline. Justin Martyr, apparently writing shortly before his death in 165 CE mentions several early “heretics”, among them Saturninus, whose followers called themselves Christians:

These men call themselves Christians in much the same way as some Gentiles engrave the name of God upon their statues, and then indulge in every kind of wicked and atheistic rite. Some of these heretics are called Marcionites, some Valentinians, some Basilidians, and some Saturnilians, and others by still other names, each designated by the name of the founder of the system, just as each person who deems himself a philosopher, as I stated at the beginning of this discussion, claims that he must bear the name of the philosophy he favors from the founder of that particular school of philosophy. (Trypho, 35.6)

The bishop Irenaeus was writing “before 180 CE” about leaders he understood to be early teachers of “heretical” views around and prior to the 130s CE and also speaks of Saturninus and prefers to arrange the names in a sequential genealogy of teachings.

And the disciples were called Christians first in Antioch. — Acts 11:26

The successor of Simon [Magus] was Menander, a Samaritan by birth. . . . . Saturninus, who was of Antioch near Daphne, and Basilides got their start from these heretics. Still they taught different doctrines, the one in Syria, the other in Alexandria. Saturninus, following Menander . . . . (Against Heresies, 1.23.5-24.1)

Saturninus/Satornilus/Satorneilos/Satornil

I will use the Latin rendering of the name, Saturninus, but will return shortly to a possible significance of the Greek form. (Irenaeus originally wrote in Greek and would have used one of the other forms of the name.) What is of significance here is the teaching on god and the Jewish law attributed to Saturninus, a figure estimated to have been active in Antioch, Syria, in the 120s CE. Since we have been talking about the establishment of “schools”, with “Christian” teachers following the ways of philosophical schools of the time, M. David Litwa’s comment is of interest:

Eusebius dated Saturninus to the reign of the emperor Hadrian (117–138 CE). In the same context, the church historian said that Saturninus set up a “school” (didaskaleion), depicting him more as a philosopher than as a religious leader. Nonetheless, we should not exclude the idea that Saturninus’s “school” did double duty as a small, ecclesial formation within a larger network of Christian assemblies in Antioch (among them the networks of Menander and Ignatius, for instance). (Litwa, 77)

If, as seems likely, Saturninus was active at a time of widespread and extreme hostility towards Jews in the eastern part of the Roman empire, the following characterization of his teaching should not be surprising:

Saturninus’s theology . . . expresses a strongly anti-Judaic stance insofar as it openly sought to discredit the Judean deity. . . .

Despite Saturninus’s seeming antagonism toward the Judean deity, he was deeply familiar with Judean scriptures and traditions . . . .

The theological seeds sown by Saturninus bore much fruit. Along with Johannine Christians, Saturninians were among the first to create a strong ideological boundary between their group and competing Jewish (and Christian) circles who worshiped the Jewish deity. Saturninus is the first known Antiochene theologian whose theology derives largely from the exegesis of scriptural texts (with a healthy dose of Jewish tradition). He was determined to revise the book of Genesis. In this revision, Saturninus was the first Christian clearly to identify the Judean god as an angel, one of seven wicked creators. This was a fateful move, proving influential for Marcion . . . . (Litwa, 77f, 82)

The link between Saturninus’s anti-Judaic theology and his historical situation was noted long ago by Robert Grant:

The historical environment of Saturninus was not purely theological. . . It included at least one Jewish revolt against the Romans, in the years 115-117, and perhaps another, in 132—135. Both revolts were disastrous for those who took part in them. Both revolts, as we have already pointed out (see Chapter 1), led radical dualist Jews and Christians to move from apocalyptic toward gnosis, and to reinterpret the Old Testament in a new way. Examining the Heilsgeschichte of Saturninus we shall find that such a reinterpretation is what he is trying to provide. (Grant, 99f — Grant is assuming the traditional first century dates for much of the New Testament literature. I am suggesting that possibly all of the New Testament literature is from the second century.)

Saturninus taught that the world and humankind were created by seven angels, one of whom was the god identified as the creator in Genesis. A higher god had created these angels, including one who was known as Yahweh.

But one of these angels is “the God of the Jews,” and the latter seems to be more important than the others, since Christ came into the world “for the destruction of the God of the Jews and for the salvation of those who believe in him [Jesus Christ].” This is what we read in the Latin translation of Irenaeus summarizing Saturnilus’s doctrine (Adv. haer. I, 24, 2), and also in the Greek text of Hippolytus (Ref. VII, 28, 5). . . . It is almost beyond doubt that for Saturnilus . . . the God of the Jews is the head of the creator angels (d. Irenaeus, I, 24, 4). He can therefore be spoken of as the principal creator.

Thus, according to Saturnilus, the God of the Old Testament is in reality an angel; that is, he is not the true God. As for the reasons that led to the devaluation of this figure, we find them without difficulty in an anti-Judaism and an anticosmic attitude that go much further than those of John. [Unlike the Gospel of John, Saturnilus taught that] Christ came into the world to destroy the God of the prophets and the old Law. . . .

We also learn from Irenaeus’s account that, according to Saturnilus, up to the coming of Christ the demons helped the wickedest human beings, and that this is why Christ came, in order to help the good and destroy the evil and the demons. This seems to mean that the persons in the Old Testament who are depicted as having been prosperous, happy and victorious were in general the most evil, which is to say that the Old Testament depicts men and judges history contrary to the truth; it is to open the door to those Gnostics who declared themselves in favor of the reprobate in the Old Testament. . . . All this manifests an anti-Judaism, or more precisely an antinomianism, a criticism of the Old Testament, that is not found in John . . . (Pétrement, 329f — my bolding)

Roger Parvus proposed the possibility that the Ascension of Isaiah lies behind some passages in our letters of Paul, and that the figure of Paul may be related in some way to Saturninus (compare the Greek form of the name, Sartornilus, with Saulos, the first name of Paul according to Acts):

I suspect the 120s are a little late for the revival of interest in a historical prophet crucified by Pilate. The more likely scenario is that a second Joshua (Greek: Jesus; see also the posts on the name of Jesus from a classicist’s perspective) was chosen to overthrow the cult and teachings of Moses. This Jesus came to earth to trick the wicked powers into crucifying him so that the good could be released from the power of death. There was no heavenly crucifixion as some have attempted to argue. The Saviour figure took on the forms of the angels in the respective heavens on his way down to earth in order not to be recognized as he passed by. In the same way he took on the form of a human in order to hide his true identity while on earth.

But if Saturninus was one of the first to expound teachings that came to have a close relationship to our idea of Christianity, they were in time supplanted by a more positive and appealing narrative: a story in which the Jewish Scriptures were not only superseded but fulfilled, or given a radically new meaning. Instead of coming to destroy the law Jesus was said to have fulfilled it, and even have bound up in himself a spiritual Moses, a spiritual Elijah, a spiritual David. This was a time of “the Second Sophistic” in literature, and a time of applying allegorical insights to bring out new meanings in old myths and narratives. A new narrative biography, like those of the philosophers, was composed in our gospels. This new narrative, better than other narratives like the Ascension of Isaiah or tales of demonic creators, could be read as a key to discovering new and “higher” meanings in Scriptures. That narrative thereby acquired the added depth that came from those Scriptures while supplanting the “Jewishness” that those Scriptures had long upheld, but that had proved a failure and a loathing to the world by the apocalyptic events in the times of Trajan and Hadrian. But the story of that new narrative would likely transfer us from Antioch to Rome.

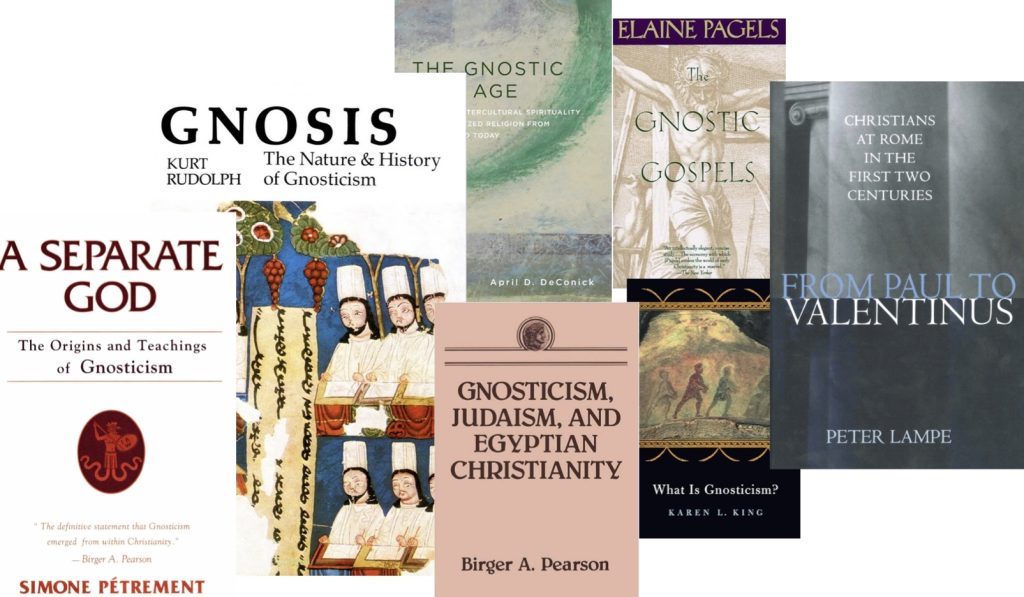

Grant, Robert M. Gnosticism and Early Christianity. New York: Columbia University Press, 1959.

Litwa, M. David. Found Christianities: Remaking the World of the Second Century CE. London ; New York: T&T Clark, 2022.

Livesey, Nina E. The Letters of Paul in Their Roman Literary Context: Reassessing Apostolic Authorship. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2024.

Lohr, Winrich. “Justin Martyr.” In From Thomas to Tertullian: Christian Literary Receptions of Jesus in the Second and Third Centuries CE, edited by Chris Keith, Helen K. Bond, Christine Jacobi, and Jens Schröter, 433–48. The Reception of Jesus in the First Three Centuries. T&T Clark, 2020.

Pearson, Birger. Gnosticism, Judaism, and Egyptian Christianity. Minneapolis: Augsburg Fortress Publishers, 1990.

Petrement, Simone. A Separate God: The Christian Origins of Gnosticism. Translated by Carol Harrison. San Francisco: HarperCollins, 1993.

Unger, Dominic J., trans. St. Irenaeus of Lyons: Against the Heresies Book 1. Ancient Christian Writers 55. New York, N.Y: The Newman Press, 1991.

Like this:

Like Loading...