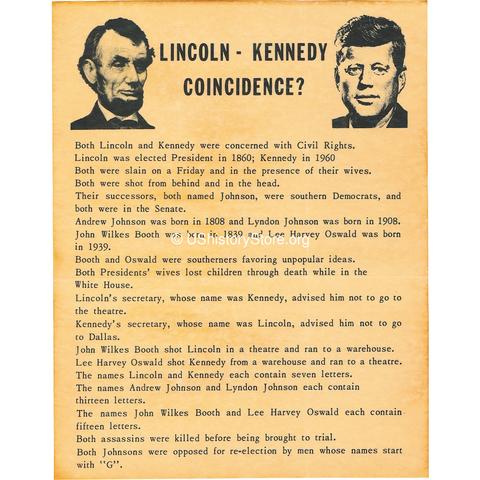

In mid-March this year James McGrath alerted readers to a new post by Tim O’Neill of History for Atheists, Jesus Mythicism 4: Jesus as an Amalgam of Many Figures, commending it for its take down of “amalgam Jesus” theorists for supposedly uncritically and emotionally concocting excuses to disbelieve in a historical Jesus. O’Neill inferred in his post that there was nothing “scholarly and credible” about parallels between a certain Jesus son of Ananias, a mad-man who Cassandra-like proclaimed doom for Jerusalem at the hands of the surrounding Roman armies, and the Jesus we read about in the Gospel of Mark. He also strongly inferred that drawing parallels between the assassinations of Lincoln and Kennedy provided ample justification for dismissing parallels between two written narratives about different Jesus figures.

In response I have demonstrated that contrary to O’Neill’s attempt to inform readers “what is scholarly and credible and what is not” scholars have indeed engaged in scholarly discussions about what some of them describe as “astonishing” and “striking” parallels. I have also posted (in a post and another in a comment) on two scholarly responses debunking as logically fallacious the attempt to use the Lincoln-Kennedy parallels in the way O’Neill uses them.

Better Informed History for Atheists — Scholars assess the Two Jesus Parallels

Even Better Informed History for Atheists: The Lincoln – Kennedy Parallels Fallacy

Still Better Informed History for Atheists — More Scholars assess the Two Jesus Parallels

Now, in what I expect will be my final post demonstrating the scholarly status of discussion about the relationships between the two Jesus figures, the one in Josephus’s Jewish War and the other in the synoptic gospels, specifically the Gospel of Mark, I will copy the preface by Mahlon Smith to the publication of Ted Weeden’s thesis in Forum, Westar’s academic journal, Fall 2003.

To begin, notice the scholarly status of the persons introducing the thesis in Forum:

Mahlon H. Smith is the new editor of Forum. He recently retired as Associate Professor and former chair of the Religion Department at Rutgers University in New Brunswick, NJ. He is co-author with Robert W. Funk of The Gospel of Mark: Red Letter Edition (1990), and served as program chair of the Jesus Seminar (1991-1996). He created and maintains the academic website, Virtual Religion Network.

Theodore J. Weeden, Sr. is author of an influential study of the composition of the first synoptic gospel, Mark—Traditions in Conflict (1971, 1979). From 1969-1981 he served as professor of New Testament at several schools that became partners in the Rochester Center for Theological Studies (Colgate Rochester Divinity School, Crozer Theological and St. Bernard’s Seminaries). He recently retired as senior pastor of Asbury United Methodist Church in Rochester, NY (1977-1995).

Here is Smith’s preface to Weeden’s thesis on the parallels, from pages 133-134:

Preface

This issue of FORUM represents a departure from our usual format in that it is devoted to publication of a single important provocative thesis. Ted Weeden’s carefully argued case that the canonical gospel narratives of Jesus of Nazareth’s confrontations with temple and Roman authorities in Jerusalem are modeled on the story of a later peasant prophet with the same given name, Jesus son of Ananias (Yeshu bar Hanania), has far-reaching ramifications for both the question of the historical Jesus and gospel criticism in general.

Scholars have long proposed that the gospels conflate two originally distinct strands of tradition about Jesus: one stemming from Galilee, the other from Jerusalem. Weeden’s thesis goes further in claiming that they also confuse two distinct Jesuses and that the structure and many details of gospel accounts of Jesus in Jerusalem represent fictive imitation of the description of the later Jesus preserved in Josephus’ account of the Jewish War 6.300-309.

In his original thesis Weeden avoided objection by any who date the gospels earlier than Josephus by assuming that the hypotext imitated by the gospel writers was the oral tradition about Jesus son of Ananias cited by Josephus rather than any written draft of the Jewish War itself. After discussion by the Jesus Seminar, however, Weeden revised his position to conclude that Josephus himself created the story of Jesus son of Ananias and that Mark used his account. If this is the case, Mark could have been composed no earlier than 80 ce. That argument is presented here in an epilogue to the original paper.

As Weeden notes, other scholars have previously called attention to similarities between the gospels’ depiction of Jesus of Nazareth and Josephus report about Jesus son of Ananias. But this is the first detailed case for the evangelists direct dependence on the latter story using the classic Greek rhetorical convention of creative imitation (mimesis).

This thesis has significance for both source and redaction criticism, for it identifies a story independently preserved in an extant text (Josephus Jewish as a source for the gospels of Mark, Luke and John. Widespread acceptance of Markan priority by scholars trained in literary criticism has led to important advances in understanding the composition of the later synoptics. But the lack of demonstrable literary models for the narratives of Mark and John has inevitably made interpretation of these authors’ redactional strategies more speculative and tentative. By tracing structural and thematic parallels between Josephus’ story of Jesus son of Ananias and Jesus of Nazareth’s confrontations with authorities in Jerusalem, not only in Mark but also in aspects of the Lukan and Johannine accounts that differ from Mark, Weeden builds his case for the widespread and enduring influence of the story of the second Jesus upon the early Christian imagination and makes Luke’s and John’s differences from the Markan narrative less arbitrary. For, if Luke and John altered Mark’s account to conform more to another hypotext, their departures from their presumed Markan paradigm cannot be credited to idiosyncratic tendencies of the gospel redactors.

Weeden lays out his case in five sections. In part 1A on Markan dependence, he surveys assessments of parallels between the stories of the two Jesuses noticed by other scholars, adds others, and argues that the cumulative literary Gestalt in the sequence of these parallels suggests intertextuality between these accounts. Then, Weeden points out that tensions in Mark’s own narrative where the author abandons themes he had previously used which parallel the story of Jesus son of Ananias reflect Mark’s own Christological and pastoral interests.

In part IB Weeden explores Mark’s identification of his subject as Jesus of Nazareth, concluding that this is a deliberate attempt to prevent confusion with the more recent prophetic figure named Jesus. Finally, he tests his theory of Markan imitation of the story of Jesus son of Ananias by weighing it against methodological criteria for identifying textual mimesis in Greek literature and citing examples of Mark’s creative reworking of stories of David.

In part 2 Weeden explores Luke’s departures from Mark’s Passion narrative, lays out parallels between Luke’s account of Jesus’ trials and the story of Jesus son of Ananias, on the one hand, and the oracles of both Jesuses against Jerusalem, on the other, and argues that these indicate deliberate mimesis rather than mere coincidence.

In part 3 Weeden examines parallels between distinctive features of the Johannine accounts of Jesus’ hearings by Judean and Roman authorities and the story of Jesus son of Ananias, including John’s emphasis on Jesus’ confrontations during feasts and his uncharacteristic emphasis on Jesus’ silence under cross-examination.

In part IV Weeden summarizes his conclusions and details the implications of his findings. An addendum details his case for the northern Palestinian provenance of Mark’s gospel; and a subsequent epilogue reaches the conclusion that Josephus himself modeled the story of Jesus son on Ananias on the figure of Jeremiah and that Mark depended directly on Josephus’ account.

Weeden’s thesis was the focal point of debate at the Fall 2003 session of the Jesus Seminar. Unfortunately, this issue has been delayed by the untimely death of FORUM’s editor, Daryl Schmidt, who devoted more than a decade to insuring the quality of the contents of this journal.

—Mahlon H. Smith

FORUM new series 6,2 Fall 2003

Perhaps a kind reader might like to leave a comment on History for Atheists advising readers of what scholars deem to be “scholarly and credible“.

And thanks to the very kind reader who sent me a copy of the Forum article.

Like this:

Like Loading...

From Rosa Rubicondior

From Rosa Rubicondior

From René Salm’s Mythicist Papers

From René Salm’s Mythicist Papers Oh no, from Salon.com, some frightening news!

Oh no, from Salon.com, some frightening news!