Recently on Vridar, Neil posted about the untimely passing of Hermann Detering. A person commented with a link to his own blog, in which he called Detering a crank, and described Vridar as a blog that is “run by a fraternity who hope that Jesus never existed.” While I am a huge fan of unintended irony, we had to block the fellow for being a boor.

In his post, he defended the use of paleography (or as citizens of the Commonwealth spell it, palaeography) as a means for dating ancient documents. Detering, he insisted, didn’t know what he was talking about.

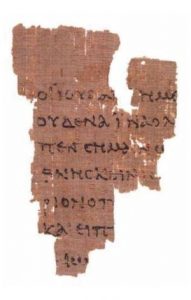

We can’t deny that when all else fails, paleography is sometimes the only way to guess at a date range for a given manuscript or fragment thereof. Unfortunately, it is the worst of all methods available to us. Here are some reasons why:

- Paleographic results are almost always tentative, but frequently overstated by amateurs and professionals alike. For example, the Rylands Library Papyrus 𝔓52 was tentatively dated to the first half of the second century. Conservative scholars have continually pushed that date to the beginning of the century with little more reason than wanting it to be so.

- Paleographic dating is a judgment call, based on many different factors. Unfortunately, scholars don’t always realize when their faith clouds their judgment. For example, several scholars dismissed Morton Smith’s letter from Mar Saba, which referred to a Secret Gospel of Mark, based in part on faulty and biased paleographic analysis.

- Using one papyrus to date another is often misleading, because scholars (either knowingly or not) compare them using the same circular reasoning — i.e., a manuscript of uncertain date is used to firm up the date of another manuscript of equally uncertain date.

That last item struck me once again as I was re-reading Brent Nongbri’s “The Use and Abuse of 𝔓52: Papyrological Pitfalls in the Dating of the Fourth Gospel.” (Note: The previous URL links to a PDF file on the Wayback Machine.)

He writes:

The original editors of this set of fragments dated it to the middle of the second century, but the problematic nature of paleographically dating these papyri comes into even sharper relief when we notice that the principle comparanda for dating Egerton Papyrus 2 are for the most part the same as those later used by Roberts to date 𝔓52. The independent value of Egerton Papyrus 2 for dating 𝔓52 is thus minimal. (Nongbri, p. 34)

It seems no matter where we dig in NT studies, we find problems of circularity. Nongbri writes, in a footnote:

Even though some literary papyri have come to light that bear a resemblance to 𝔓52 . . . they are of no help in the present project since they are themselves paleographically dated. Although Turner recommends comparing literary hands with literary hands, such a process can become very circular without the inclusion of some firmly dated (usually documentary) manuscripts to act as a control. (Nongbri, p. 46, emphasis mine)

Once again, that pesky word rears its ugly head. We always need controls. What kinds of controls? Independent attestation, physical evidence, eyewitness accounts, and in this case, something “firmly dated” using a reliable method, rather than the comparison of scribal handwriting.

Tim Widowfield

Latest posts by Tim Widowfield (see all)

- What Did Marx Say Was the Cause of the American Civil War? (Part 1) - 2024-05-12 19:09:26 GMT+0000

- How Did Scholars View the Gospels During the “First Quest”? (Part 1) - 2024-01-04 00:17:10 GMT+0000

- The Memory Mavens, Part 14: Halbwachs and the Pilgrim of Bordeaux - 2023-08-17 20:39:42 GMT+0000

If you enjoyed this post, please consider donating to Vridar. Thanks!

Paleography – if I use Gothic font in a document that won’t mean I wrote it in the 14th century.

The criticism of Detering referred to far later manuscripts on vellum, but it’s not exactly easy to check any of the claims, since neither the manuscripts themselves nor the analysis behind the dating is readily available online.

According to this the oldest manuscript is written in half uncials https://www.jstor.org/stable/23963211?seq=1#page_scan_tab_contents

Wikipedia says those went out of fashion in the 800s https://en.m.wikipedia.org/wiki/Uncial_script

That seems a bit hard to square with Detering’s suggestion that Anselm is the forget (died 1109).

In principle, if Anselm were a forger, he might presumably use an ancient script for the purpose. So that’s not dispositive. Even so, one still needs evidence to conclude forgery; and I do find Detering, in this as in much of his work, all too often substituted speculation for evidence, and ran rampant with possibiliter fallacies (“possibly x, therefore x”). Which doesn’t discredit all his arguments and insights. It just means, much of them are unreliable; proposals at best, rather than conclusions, and it was wrong to paint the one as the other.

On paleographic dating though, typical comparators (from which chronological script databases are built) are dated in the manuscript itself (i.e. the scribe actually says when it was written) or by in situ provenance (i.e. in what dig layer it’s found). Larry Hurtado has much to say on the point, e.g. here and here and indeed here, given that the latter references the rather brilliant revisionist work of Brent Nongbri (who wrote up an extensive treatise on the subject in God’s Library).

One need merely compare Nongbri’s work with Detering’s to see the enormous difference between evidence-based revisionism and speculative revisionism being sold as fact. This is pretty much the whole difference people are keying on when they look side-eyed at Detering’s work and even perhaps suggest he was a crank. Detering’s work is galaxies apart from work like Nongbri’s. And in ways that do indeed border on the difference between professional and crank scholarship, at least close enough to make some people suspicious.

I’m not invested in either conclusion. But I do understand why some people feel this way.

Dr. Carrier, how pleasant and informative your words are about this topic. It seems, alas that the Bible attracts a lot of cranks and that any interpretation of the Bible that goes too far outside the scholarly mainstream is dismissed – rightly or wrongly – as crankery.

Speaking of that, are you planning a re4sponse to the critique of your use of the story of Romulus to explain Christ mythicism?

Dr. Carrier, I would be interested in your review of “O du lieber Augustin.” I have not found it yet.