I have been posting on the works of several scholars who argue that the Old Testament scriptures were composed much later than traditionally thought (Thompson, Davies, Lemche, Wesselius, Wajdenbaum) but there remains much more to be written about their arguments, and more published scholars to draw into the same net (Nielsen and Gmirkin are two of these). This post introduces the work of Russell E. Gmirkin. I look forward eventually to discussing where his criticisms intertwine with those of Wajdenbaum and others, and then to return to Wajdenbaum’s thesis that the Old Testament books are heavily indebted to classical Greek literature and myths. But there is much to be covered in the meantime, including further exploration into the similarities between the Histories by Herodotus and the collection of books from Genesis to 2 Kings (referred to as The Primary History) in the Bible. Gmirkin does not support the thesis that the biblical author borrowed from Herodotus, however. It’s a fascinating time to be reading a rich range of new views about the origins of the Hebrew Bible.

I have been posting on the works of several scholars who argue that the Old Testament scriptures were composed much later than traditionally thought (Thompson, Davies, Lemche, Wesselius, Wajdenbaum) but there remains much more to be written about their arguments, and more published scholars to draw into the same net (Nielsen and Gmirkin are two of these). This post introduces the work of Russell E. Gmirkin. I look forward eventually to discussing where his criticisms intertwine with those of Wajdenbaum and others, and then to return to Wajdenbaum’s thesis that the Old Testament books are heavily indebted to classical Greek literature and myths. But there is much to be covered in the meantime, including further exploration into the similarities between the Histories by Herodotus and the collection of books from Genesis to 2 Kings (referred to as The Primary History) in the Bible. Gmirkin does not support the thesis that the biblical author borrowed from Herodotus, however. It’s a fascinating time to be reading a rich range of new views about the origins of the Hebrew Bible.

Russell E. Gmirkin’s book, Berossus and Genesis, Manetho and Exodus: Hellenistic Histories and the Date of the Pentateuch, has attracted wildly different reviews. One can read some of these here, here and here. But just as interesting is to read how Gmirkin himself evaluates some of the views of (at least one of) the authors of one of the particularly “bad” reviews. But for anyone interested in exploring new scholarly understandings of the Old Testament Gmirkin’s ideas will certainly be thought-provoking. (I was made aware of Gmirkin’s book through a passing comment left on this blog by Niels Peter Lemche.)

I’ve also found a Youtube video outlining key parts of his thesis. But contrary to what this video appears to imply, Gmirkin himself does not (as far as I can tell) argue for the “primacy” of the Septuagint. He writes on page 249:

From the foregoing discussion, it appears that the activities of the Septuagint scholars of 273-272 BCE included composing the Pentateuch in Hebrew as well as translating it into Greek.

He argues for the two — the Greek and Hebrew versions — appearing around the same time.

http://www.youtube.com/watch?feature=player_embedded&v=awg52anmTb8

Here is how Russell Gmirkin himself introduces his thesis (my own emphasis and formatting as for all quotations):

This book proposes a new theory regarding the date and circumstances of the composition of the Pentateuch. The central thesis of this book is that the Hebrew Pentateuch was composed in its entirety about 273-272 BCE by Jewish scholars at Alexandria that later traditions credited with the Septuagint translation of the Pentateuch into Greek.

The primary evidence is

- literary dependence of Gen 1— 11 on Berossus’s Babyloniaca (278 BCE),

- literary dependence of the Exodus story on Manetho’s Aegyptiaca (ca. 285-280 BCE),

- and datable geo-political references in the Table of Nations.

A number of indications point to a provenance of Alexandria in Egypt for at least some portions of the Pentateuch. That the Pentateuch, utilizing literary sources found at the Great Library of Alexandria, was composed at almost the same date as the Alexandrian Septuagint translation provides compelling evidence for some level of communication and collaboration between the authors of the Pentateuch and the Septuagint scholars at Alexandria’s Museum.

The late date of the Pentateuch, as demonstrated by literary dependence on Berossus and Manetho, has two important consequences:

- the definitive overthrow of the chronological framework of the Documentary Hypothesis,

- and a third-century BCE or later date for other portions of the Hebrew Bible that show literary dependence on the Pentateuch. (p. 1)

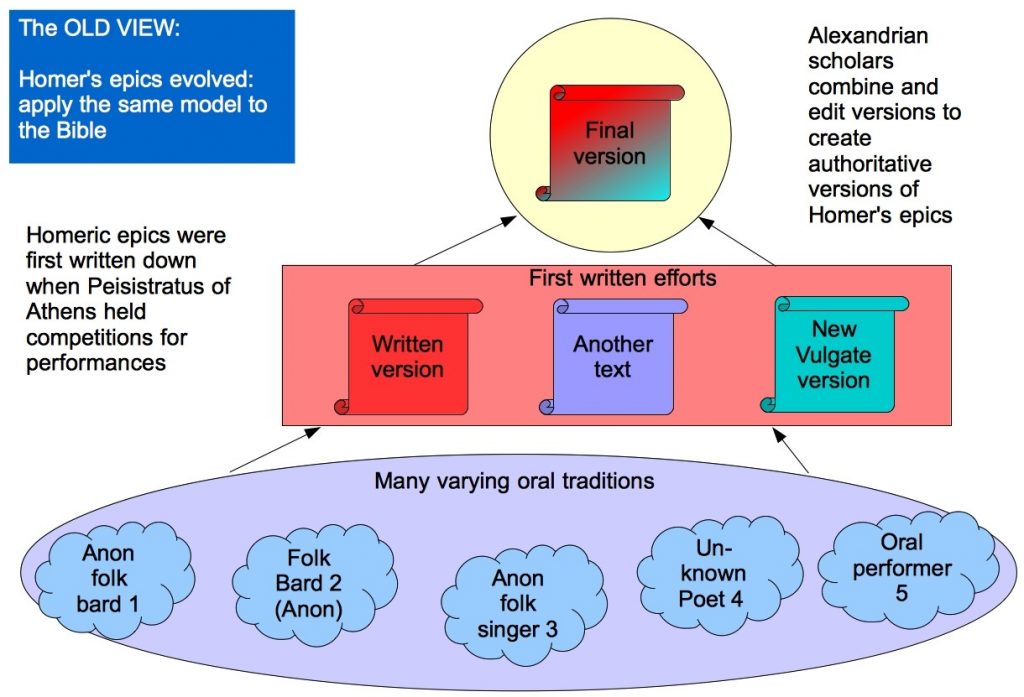

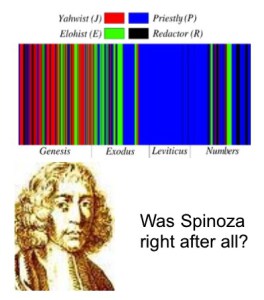

Compare the outcome of criticisms of the Documentary Hypothesis — the thesis that the Old Testament books can be pulled apart into different sources or strata — Priestly, Jahwist, Elohist and Deuteronomist (and a later Redactor).

Compare the outcome of criticisms of the Documentary Hypothesis — the thesis that the Old Testament books can be pulled apart into different sources or strata — Priestly, Jahwist, Elohist and Deuteronomist (and a later Redactor).