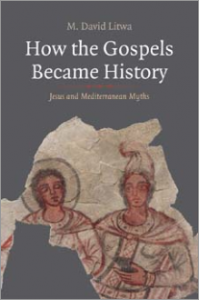

I have been slow posting with the first few pages of M. David Litwa’s How the Gospels Became History but I hope the time I’ve taken with the foundations (see various recent posts on ancient historians) will pay off when I get into the main argument. A reason I have taken a detour with readings of ancient Greco-Roman historians is the difficulty I have had with some of Litwa’s explanations in his introductory chapter. Was I reading contradictions or was I simply not understanding? I’m still not entirely sure so I’ll leave you to think it through.

I have been slow posting with the first few pages of M. David Litwa’s How the Gospels Became History but I hope the time I’ve taken with the foundations (see various recent posts on ancient historians) will pay off when I get into the main argument. A reason I have taken a detour with readings of ancient Greco-Roman historians is the difficulty I have had with some of Litwa’s explanations in his introductory chapter. Was I reading contradictions or was I simply not understanding? I’m still not entirely sure so I’ll leave you to think it through.

Litwa will set out a case that educated non-Christians would have read the gospels as a certain type of history:

I propose that educated non-Christian readers in the Greco-Roman world would have viewed the gospels as something like mythical historiographies—records of actually occurring events that nonetheless included fantastical elements. . . . There was at the time an independent interest in the literature of paradoxography, or wonder tales.67 Literature that recounted unusual events especially about eastern sages would not have been automatically rejected as unhistorical.

Even as the evangelists recounted the awe-inspiring wonders of their hero, they managed to keep their stories within the flexible bounds of historiography. They were thus able to provide the best of both worlds: an entertaining narrative that, for all its marvels, still appeared to be a record of actual events. In other words, even as the evangelists preserved fantastical elements (to mythödes) in their narratives, they maintained a kind of baseline plausibility to gesture toward the cultured readers of their time.

67 – the citation is to mid-second century records

(Litwa, 12. Bolding and formatting are mine in all quotations)

I interpret this particular comment to mean that the gospel narratives were similar to other historical writings of the time insofar as they sprinkled a tale of “normal” (i.e. plausible) human activities with stories of miracles and wonders. That is, the main (“normal”, “plausible”) narrative (represented by green blocks) flows independently of the sporadic wonder tales (purple with sun disc). The wonder tales add entertainment but the story itself does not depend on them. They can be omitted without any damage to the main narrative.

Examples in Greco-Roman histories: where an author inserts a tale that “they say” but leaves it open to the reader whether to believe it or not. For some examples, see The Relationship between Myth and History among Ancient Authors. Usually the “wonder story” is only loosely integrated into the larger realistic account by rhetorical devices such as “they say” or “there is a story that” or “poets have written” or “a less realistic account that is well known…” etcetera.

Examples in noncanonical gospels: Jesus being “born” by suddenly appearing beside Mary after a two-month pregnancy (Ascension of Isaiah); Jesus causing clay pigeons to come alive (Infancy Gospel of Thomas). . . . Tales of wonder that entertain as interludes rather than drive the plot.

In the canonical gospels, on the other hand, miracles are an essential part of the respective plots. To see how true this is, try reading the Gospel of Mark after first deleting or covering up the episodes of the miraculous, the divine or spirit world, mind-reading, and other supernatural inferences. One is left with a story that makes no sense. Was it because of an argument over unwashed hands that Jesus was crucified, for example? In the canonical gospels, the miracles are essential to the plot development: they are what bring notoriety to Jesus and identify him as the one whom the priests must, through jealousy, get rid of. The gospel narratives simply don’t work as stories without Jesus’ ability to perform miracles and demonstrate (though he is not obviously recognized as such by the human actors) his divine nature. The Greco-Roman histories would lose some entertainment value by omitting certain miracles but their fundamental narratives would still survive.

The tales of wonder in the gospels are (1) rich with theological meaning (e.g. feeding multitudes in the wilderness represents a “greater Moses” or shepherd role of Jesus) and (2) integral to the plot (e.g. the miracles set in train the events that lead to the atoning death of Jesus).

Hence I find Litwa’s thesis difficult to accept in the light of what we know of Greco-Roman histories. In the gospels, the tales of wonder themselves must be understood as the historical events, essential to the historical narrative, not optional entertainment along the way. There are not “two worlds” in the gospels, mundane and wonders, but one world in which the wonders are as essentially historical as the preaching and the debates.