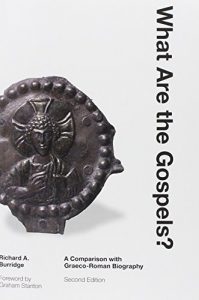

It is a naive mistake to approach every ancient narrative that purports to be about past events on the assumption that we can take it at its word — unless and until proven wrong. Even the famous “father of history”, the Greek “historian” Herodotus, turned fables into history. The Hebrew Scriptures (Old Testament) does the same. If we are to understand how to interpret the New Testament literature we might find it useful to study ancient Hellenistic literature in general. Knowing how ancient authors worked across a wide spectrum of genres in the cultural milieu preceding and surrounding the time of the Gospels might lead to an understanding otherwise lost to us. If nothing else, a broad understanding of how ancient texts “worked” will alert us to possibilities that need to be considered and evaluated when we do read the Gospels.

It is a naive mistake to approach every ancient narrative that purports to be about past events on the assumption that we can take it at its word — unless and until proven wrong. Even the famous “father of history”, the Greek “historian” Herodotus, turned fables into history. The Hebrew Scriptures (Old Testament) does the same. If we are to understand how to interpret the New Testament literature we might find it useful to study ancient Hellenistic literature in general. Knowing how ancient authors worked across a wide spectrum of genres in the cultural milieu preceding and surrounding the time of the Gospels might lead to an understanding otherwise lost to us. If nothing else, a broad understanding of how ancient texts “worked” will alert us to possibilities that need to be considered and evaluated when we do read the Gospels.

I focus in this post on Herodotus and draw out lessons from modern critical studies that might profit us in reading the Gospels and Acts, perhaps even the New Testament epistles.

In school I learned that Herodotus was “a credulous collector of anecdotal data”. That was wrong. That perception was the result of taking his writings at face-value and making modern-reader judgments about that face-value reading. That’s not good enough and leaves the door open to many misreadings of the text. Continue reading “Reading an ancient historical narrative: two fundamental principles”