Continuing the series on Thomas Brodie’s Beyond the Quest for the Historical Jesus: Memoir of a Discovery, archived here.

Continuing the series on Thomas Brodie’s Beyond the Quest for the Historical Jesus: Memoir of a Discovery, archived here.

Chapter 17

A MARGINAL JEW: RETHINKING THE HISTORICAL JESUS —

THE MONUMENTAL WORK OF JOHN P. MEIER

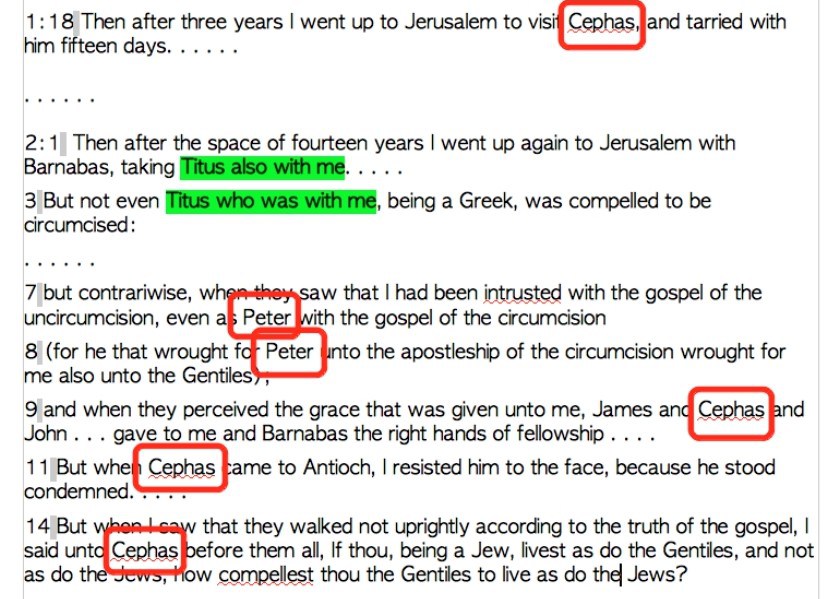

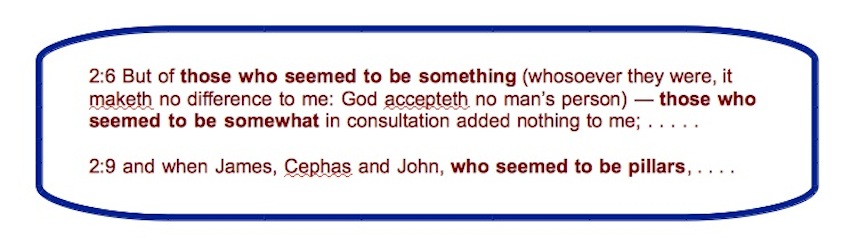

Thomas Brodie selects for discussion John Meier’s work, A Marginal Jew, as representative of the best work that has been published on the historical Jesus by a range of great scholars (Wright, Dunn, Levine, Freyne, Crossan, Theissen “and many others”). The five volume Marginal Jew was singled out because it is so well-known and among “the most voluminous”. To begin with, Brodie clarifies that he is not at all writing a “polemic”. That he apparently feels a need at this point in his book to stress such an obvious thing is a sad commentary on the forces he knows he is facing with the scholarly establishment. If anyone was left wondering if the mood of that establishment was softening they should be pulled up by Bart Ehrman’s recent comments:

As most of you know, I’m pretty much staying out of the mythicist debates. That is for several reasons. One is that the mythicist position is not seen as intellectually credible in my field (I’m using euphemisms here; you should see what most of my friends *actually* say about it….) . . . . and my colleagues sometimes tell me that I’m simply providing the mythicists with precisely the credibility they’re looking for even by engaging them. It’s a good point, and I take it seriously. . . . . . The other reason for staying out of the fray is that some of the mythicists are simply unpleasant human beings – mean-spirited, arrogant, ungenerous, and vicious. I just don’t enjoy having a back and forth with someone who wants to rip out my jugular. So, well, I don’t. (They also seem – to a person – to have endless time and boundless energy to argue point after point after point after point after point. I, alas, do not.)

In other words, the encounters this blog has experienced with the likes of James McGrath, Joseph Hoffmann, Larry Hurtado, Maurice Casey and a few others — encounters characterized by sarcasm and insult and avoidance in response to mythicist arguments — are apparently the norm to be expected, according to Bart Ehrman. He expresses frustration over the failure of the standard answers to answer newly engaged questioners. The answer is to despise those who are not persuaded and rather than seriously engage them in depth retreat into the authority of his ivory scholarly tower. This is not how evolutionists publicly respond to Creationist arguments in their publications that do address the serious Creationist questions. Meanwhile, Bart is effectively admitting what is clear to many of us, and that is that he is simply ignoring the mythicist counter-arguments to his claims and repeating the standard catechisms for historicity as if anything contrary or seriously challenging should be shunned as the work of intellectual lepers. Accept the arguments of the first point and don’t question the assumptions or the logic or the evidence of those answers, because the likes of Ehrman do not have time or energy to re-examine such “point after point after point” of their Conventional Wisdoms. It is interesting, too, that Ehrman uses the language of a persecution-complex, as if “mythicism” — that is said to be so marginal as to be irrelevant — is nonetheless a serious threat to the status and credibility of scholars of early Christianity. It seems that the language of persecution, with its consequent polarizing of the debates into some sort of war between good and evil, and the lurid dehumanizing of those challenging the status quo (Ehrman speaks of mythicists as “unpleasant human beings, . . . vicious . . . who want to rip out his jugular”; Hoffmann speaks of mythicists as “disease carrying mosquitoes”; etc.) has been with these scholars ever since the fourth century. But no-one can accuse Thomas Brodie of having some sort of anti-Christian agenda. Brodie in fact seeks for Christianity a deeper understanding of God. He invites Christians to courageously come to acknowledge that Jesus is something far more than any historical person could ever be: he is Truth, Reality, expressed as a literary parable or metaphor revealing great truths about God. Brodie reminds me of Albert Schweitzer’s wish for Christianity to abandon a faith based on some contingent historical event or person that would always remain open to question and to establish itself upon a deeper metaphysic. (He expressed this wish for Christianity at the conclusion of his critique of mythicist arguments of his own day.) So into the Circus to face the lions walks Brodie, pleading his innocence and freedom from polemic. Continue reading “Making of a Mythicist, Act 4, Scene 6 (Two Key Problems with Historical Jesus Studies)”