Previous posts in this series looking at Friction: How Radicalization Happens to Them and Us by Clark McCauley and Sophia Moskalenko:

Previous posts in this series looking at Friction: How Radicalization Happens to Them and Us by Clark McCauley and Sophia Moskalenko:

Starting at the Top: Rejecting Violence

Place: Russia

Year: 1875

Adrian Mikhailov was a talented Russian orphan who wanted more than anything else to use his skills to help lift impoverished peasants out of their miserable existence.

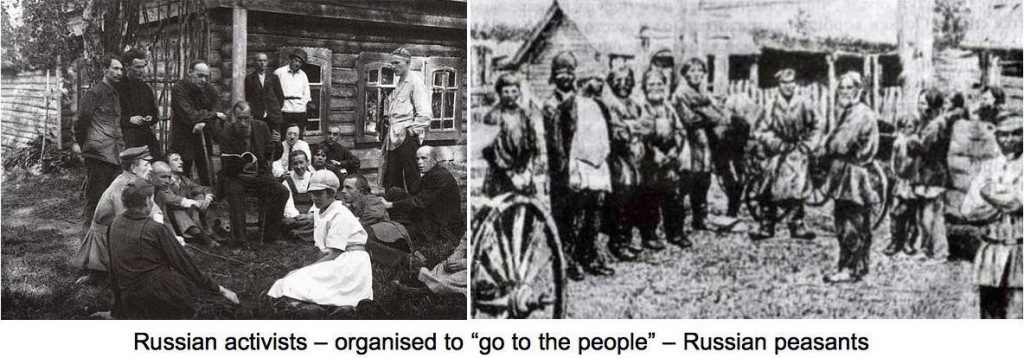

It was in boarding school, in the library attic, where his vision of a “new Russia” was inspired by writers like Chernyshevsky (author of What Is To Be Done?) and Dobrolubov. A scholarship enabled him to move to the University of Moscow where he mixed with like minded idealistic students. Their strategic vision (inspired by writings like What Is To Be Done? ) was to go to the peasants, live among them, become one of them, discuss their conditions with them and raise their awareness to understand how political action could lead to a better life. Adrian’s small commune started their own farm to work among “the people”.

Place: USA – Syria – Canada – Egypt – Somalia

Period: 1999-2001

Omar Hammami was baptized a Christian in his home state of Alabama. His mother was a Christian but Omar fell in love with the culture and people of Syria when he visited his father’s family in 1999 and soon afterwards became a Muslim. Though at first he had defended Osama bin Laden as a freedom fighter 9/11 prompted him to study his religion more seriously and he took a strong turn against politics. He turned to a Salafist interpretation of the Muslim religion that rejected involvement in politics totally. He condemned the killing of innocents and believed political interests only compromised the true values of Islam. Jihad, for Omar, was entirely a personal spiritual struggle.

Such were the positions from which Adrian and Omar began their respective slides into terrorism.

They both were opposed to violence, especially the murder of innocents, but both eventually found themselves in the thick of terrorist actions.

The Slippery Slope to Violence

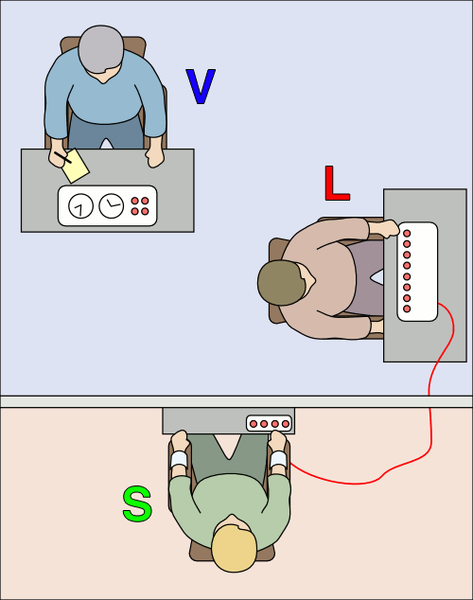

To understand how that is possible recall the Milgram experiment where participants followed directions to punish a learner who gave wrong answers with electric shocks of ever increasing severity. It’s learner was actually an actor who was not really suffering electric shocks, but the participant did not know that. Afterwards a number of the participants reported feeling some distress as they administered what they believed were ever stronger shocks but what remains noteworthy is that two-thirds of the participants nonetheless followed through with a series of small incremental steps (15 volts per step) until they “knowingly” were administering the dangerous level of 450 volts.

This experiment can be interpreted as an indicator of the willingness of people to follow the directions of an authority since it is the experimenter who instructs the participants to steadily increase the shock level. But there is an interesting “no-authority” variation to this experiment.

[I]n the “no-authority” variation, a “co-teacher” (another accomplice of the experimenter) asks and grades the questions, while the naive participant is the teacher who gives the shocks. The experimenter, summoned away for a “phone call,” is no longer in the room when the co-teacher comes up with the idea of raising the shock level with each mistake.

Despite the absence of the experimenter and his authority, 20 percent of teachers go all the way to administering 450 volts.

(McCauley, Clark; Moskalenko, Sophia (2011-02-02). Friction: How Radicalization Happens to Them and Us (Kindle Locations 904-908). Oxford University Press. Kindle Edition.)

How do explain the disturbing behaviour of one fifth of those among us?

One way to explain this result is in terms of rationalization. According to dissonance theory, humans are likely to change their opinions to fit their behavior. Especially if we have done something stupid or dishonest, we are likely to come up with reasons that will justify or excuse us.

McCauley, Clark; Moskalenko, Sophia (2011-02-02). Friction: How Radicalization Happens to Them and Us (Kindle Locations 912-913). Oxford University Press. Kindle Edition.

Or to spell it out in more detail:

The dissonance interpretation of why 20 percent of participants will administer 450 volts in the absence of authority goes as follows: The finely graded levels of shock are a slippery slope, in which the best reason to give the next higher level of shock is that a slightly lesser shock has just been given. If the next level of shock is wrong, there must be something wrong with the previous level of shock already delivered. But if there is nothing wrong with giving the immediately preceding level of shock, the next level, only 15 volts higher, cannot be wrong either. If 300 volts was OK, how can 315 volts be wrong? But if 315 volts is wrong, how could 300 volts have been right? Having already given a number of shocks, participants feel a need to justify themselves and to preserve their self-image as decent people. The justification of the previous shock then rationalizes the next level of shock.

McCauley, Clark; Moskalenko, Sophia (2011-02-02). Friction: How Radicalization Happens to Them and Us (Kindle Locations 914-920). Oxford University Press. Kindle Edition.

Subsequent interviews with the participants indicated that many of them did indeed feel some distress for their victims and were even relieved to learn that no real harm had been suffered. Their actions were not malicious. They did not feel comfortable carrying out their actions but that discomfort did not stop them.

Is it possible that some people slide into terrorism by the same process?

Adrian’s Descent

The farm, or more pointedly the radicalisation efforts, were a failure. Like other students Adrian could only find a meeting of minds with the peasants up to a point. Never would the salt of the earth countenance a bad word about their czar.

Adrian returned to Moscow without persuading a single “convert” to his credit. But he did believe in and love what he was doing and immediately sought another occupation to bring him closer to the people. This time he trained to be a blacksmith.

His student comrades, however, were more impressed with his understanding of economic theory and his ability to expound Karl Marx’s Das Kapital. Before he had an opportunity to return to the field he was invited to St Petersburg to discuss Marxist economics. His success there led him to be accepted as a member of Land and Freedom, a group that later morphed into People’s Will. But a stronger force pulled him away from them. He explained this way:

At another time and under other circumstances I would have stayed here for a long time to personally get to know this family, yes, family, of prominent workers of revolution — charming people with colorful personalities. But a stronger force pulled me away — into the people. . .

McCauley, Clark; Moskalenko, Sophia (2011-02-02). Friction: How Radicalization Happens to Them and Us (Kindle Locations 800-802). Oxford University Press. Kindle Edition.

Sadly Adrian worked himself as an obliging blacksmith into ill health and was again forced to return without having succeeded in politicizing any of the peasants.

In fact the “going to the people” movement more generally had been a failure so leading activists turned their attention to getting rid of the czar himself. Remove the peasants’ idol and they would be obliged to take action themselves to create a better society.

Adrian’s subsequent written account of his experiences indicate that he felt somewhat lost in this new change of direction. Unlike many of his colleagues he really loved living and working among the peasants. He believed the peasants’ political consciousness could be ignited eventually through peaceful means.

At the same time he felt a sense of loyalty to the activist movement of his fellow students.

First assignment:

- Adrian was to be the coachman in a plan to rescue a prominent activist prisoner. Plan failed, but Adrian had been involved in the illegal action.

Adrian requested leave to return to the peasants. His comrades did not allow him — there was too much work to do and too few to help in St Petersburg.

Second assignment:

- Adrian was to be the coachman in a plan to rescue a number of political prisoners. The plan failed, but Adrian again involved in a more daring illegal action.

Adrian again requested leave to return to the peasants. His comrades again refused his request.

Third assignment:

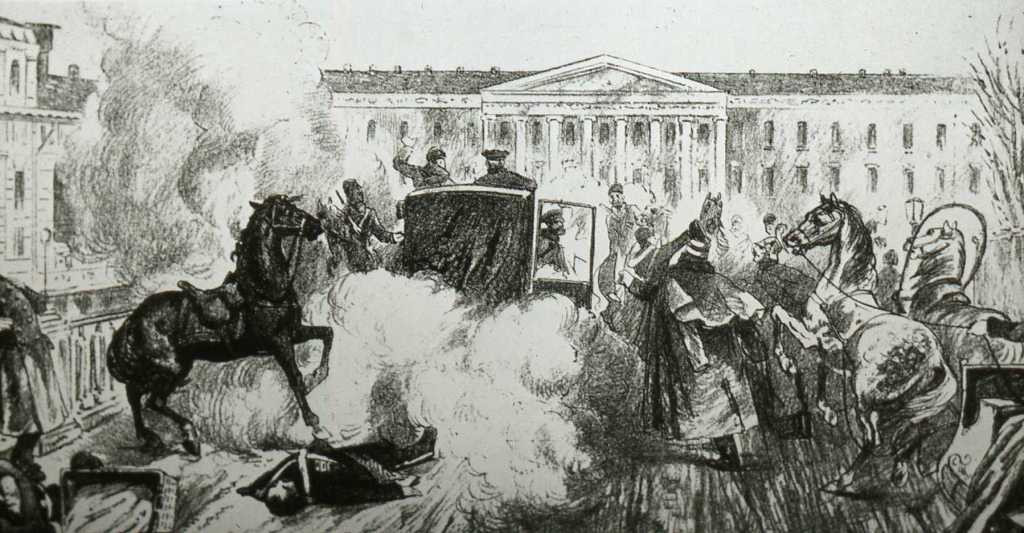

- Again the coachman role, but this time for a plan to assassinate General Mezentsev. This time the plan succeeded. All members dispersed to the countryside for their own protection.

Months later Adrian was recalled to St Petersburg to help establish a newspaper.

Authorities discovered and arrested him.

To escape hanging he gave the police the names of two of his colleagues — although one was outside Russia and unreachable and the other was an alias used by his comrade, not his real name. Nonetheless the latter was identified and captured.

In Adrian’s subsequent written account of his life he writes warmly and fulsomely of his time working alongside peasants but is consistently matter-of-fact, unemotional, brief, when covering the more intellectual and criminal activities undertaken with his fellow students. The difference in tone tells readers where his heart was.

Nonetheless, out of a sense of loyalty to his student colleagues he did find himself being drawn into activities that included murder — despite his personal disposition not to be so involved.

Omar’s Descent

Having embraced a version of the Muslim religion that rejected all interest in politics and that taught that such interest amounted to a stain on the purity of one’s faith, Omar went another step into “purity” by dropping out of college. Apparently struggling with the temptations of the flesh he felt it better to remove himself from a co-ed environment.

He followed a friend (Bernie Culveyhouse, another convert to Islam) to Toronto where he found the Muslim community much more opposed to the U.S. war in Iraq. While browsing in an Islamic bookstore someone asked him to “pray for the people of Fallujah”.

This request initiated a political awakening that led Omar to abandon his Salafi distancing from political events. After the battle of Fallujah, he became consumed with events in Iraq and Afghanistan. Later, in a 2009 e-mail interview, he explained his sudden political interest as follows: “I was finding it difficult to reconcile between having Americans attacking my brothers, at home and abroad, while I was supposed to remain completely neutral, without getting involved.”

McCauley, Clark; Moskalenko, Sophia (2011-02-02). Friction: How Radicalization Happens to Them and Us (Kindle Locations 966-969). Oxford University Press. Kindle Edition.

Now married to a Somali woman, Omar with his wife and his friend moved to Egypt with hopes of being accepted for Al-Azhar University.

They lived in Alexandria but found the city “disappointingly secular”.

Failing to gain entrance to the University, his friend returned to the United States — leaving Omar feeling betrayed and deserted.

In Egypt he began following closely the news of the conflict in his wife’s country, Somalia.

At this point he felt a call to jihad. Notice how he had graduated through circumstances and influences from a pacifist faith to a militant one.

With another friend he met in Egypt Omar began attending underground mosques and listening to radical imams.

2006, the U.S. backed Christian Ethiopian army invaded Somalia.

Omar began to appeal on the internet for action against the “infidel invaders” of Muslim Somalia. These internet appeals were his first public action.

From a dissonance-theory perspective, the more public the commitment is, the greater is the need for justifying this commitment with new and increased commitments.

McCauley, Clark; Moskalenko, Sophia (2011-02-02). Friction: How Radicalization Happens to Them and Us (Kindle Locations 1005-1006). Oxford University Press. Kindle Edition.

Note the way the following steps at each point left Omar with a way out:

- Omar told his family he was going to look for work in Dubai but instead went to Somalia.

- In Somalia he told his wife he had lost his passport and that was the reason he could not return soon.

- After Ethiopia captured Mogadishu (2006), Omar joined Shabab, the militant Islamists linked with al-Qaeda who were seeking to drive out the Ethiopians.

- 2007, Omar was the leader of Shabab. Took the name Abu Mansoor al-Amriki: — appeared in an al-Jazeera interview with mask hiding his face.

- 2008, Omar appeared in a new video leading attacks in the field. His face is uncovered: “It makes more of a statement if my face is uncovered.”

It is important to notice that he reached the peak of opinion radicalization with his Internet postings urging action against the infidel invasion of Somalia, but these postings left him still far short of full commitment to radical action. He kept open a door to disengagement with the stories he told to his wife and parents, first about visiting his wife’s family, then about a lost passport. Even after joining Shabab, he masked his face for his first video, preserving some chance of exit. Finally, with the unmasked interview, he reached the peak of final and public commitment to Shabab and its violence.

McCauley, Clark; Moskalenko, Sophia (2011-02-02). Friction: How Radicalization Happens to Them and Us (Kindle Locations 998-1002). Oxford University Press. Kindle Edition.

We thus see how Omar Hammami’s steps to his life as an Islamic warrior were gradual, a new step being taken with each new move, with each new set of contacts, with each new step towards a public commitment, first of opinions, then of actions.

In 2012 the FBI added Omar’s name to its “Most Wanted Terrorist” list.

In 2013 he was killed in a power struggle among members and former members of Shabaab.

Neil Godfrey

Latest posts by Neil Godfrey (see all)

- Questioning the Hellenistic Date for the Hebrew Bible: Circular Argument - 2024-04-25 09:18:40 GMT+0000

- Origin of the Cyrus-Messiah Myth - 2024-04-24 09:32:42 GMT+0000

- No Evidence Cyrus allowed the Jews to Return - 2024-04-22 03:59:17 GMT+0000

If you enjoyed this post, please consider donating to Vridar. Thanks!

This reminds me of the Benjamin Franklin Effect: “A person who has done or completed a favor for someone is more likely to do another favor for that person than they would be if they had received a favor from that person. Similarly, one who harms another is more willing to harm them again than the victim is to retaliate”

It’s like we have a cache of ourselves and once we’re in the same or similar situation we are more easily able to step into that role. If the situation calls for slightly more commitment, then we take that commitment on more readily.

I just read this strange FBI report about this group of car thieves who became “radicalized” and kidnapped someone. This happened only a few months ago, but it follows a similar path.

More terrorism perhaps justified by (but not caused by?) Christian beliefs: http://www.latimes.com/local/lanow/la-me-ln-suspicious-fire-planned-parenthood-20151001-story.html