I don’t know. If you thought Maurice Mergui’s ideas set out in my previous posts were over the top then you are going to totally freak out over this one. It comes from his book Un Étranger Sur Le Toit: Les Sources Misdrashiques Des Evangiles.

I don’t know. If you thought Maurice Mergui’s ideas set out in my previous posts were over the top then you are going to totally freak out over this one. It comes from his book Un Étranger Sur Le Toit: Les Sources Misdrashiques Des Evangiles.

I was looking for a new interpretation of that little healing episode where Jesus goes to Peter’s house to heal his wife’s mother who has a fever. In Mark and Matthew Jesus touches her hand and the fever leaves her; she then gets up and serves everybody. (A woman’s work, etc …) In Luke we read that Jesus rebuked the fever before it left her.

Now I’ve always had a problem with this passage as it’s told in the Gospel of Mark. In just about every other healing event there is a clear symbolic factor at work. Symbolic names and actions abound. In that context there seems to be no point to the story of healing Peter’s mother-in-law. No name, no evident symbolism, no further detail or background appears in the narrative. It appears to lack the sorts of points we find in other healings.

So I had to find out if Maurice Mergui’s midrashic interpretations had anything to offer. And oh yes, his discussion goes way, way beyond anything I had expected. But that leaves me a bit wary. Has he gone way too far and in a perverse sort of way argued his point out of the realm of plausibility? I really don’t know. Which is where I came in.

So here goes.

The usual caveats apply: I was never a top-grade student in my French classes; I have not been able to track down all of his sources, in particular, an English translation of Exodus Rabbah 50; I have not read his complete chapter, let alone the entire book, so may well be missing some key details that would shift some of my understanding; and I am not even going to cover every detail within the section I have attempted to grasp (because some points still elude me); and I sometimes have suspicions that the Kindle version of the book fails to capture correctly the transliterations of the Hebrew that I would expect to see in the original. Anyone with a better grasp of French is very welcome to add to /correct whatever follows.

Here is the passage being addressed:

Matthew 8 (Mergui sees major significance in Matthew’s placing this healing immediately after the healing of the centurion’s son. I have not explored his discussion on that link, so forgive me for missing something he considers important here — at least for now.) . . .

14 When Jesus came into Peter’s house, he saw Peter’s mother-in-law lying in bed with a fever. 15 He touched her hand and the fever left her, and she got up and began to wait on him.

16 When evening came, many who were demon-possessed were brought to him, and he drove out the spirits with a word and healed all the sick

Mark 1

29 As soon as they left the synagogue, they went with James and John to the home of Simon and Andrew. 30 Simon’s mother-in-law was in bed with a fever, and they immediately told Jesus about her. 31 So he went to her, took her hand and helped her up. The fever left her and she began to wait on them.

32 That evening after sunset the people brought to Jesus all the sick and demon-possessed.

Luke 4

38 Jesus left the synagogue and went to the home of Simon. Now Simon’s mother-in-law was suffering from a high fever, and they asked Jesus to help her. 39 So he bent over her and rebuked the fever, and it left her. She got up at once and began to wait on them.

40 At sunset, the people brought to Jesus all who had various kinds of sickness, and laying his hands on each one, he healed them.

Mergui begins by pointing out that our little story is all very simple, straightforward, and poses no mysteries, etc. (Except that that’s what I think is so out of character for it for several reasons.) But let’s imagine a Hebrew original, Mergui proposes, and see what happens.

Key words in Hebrew all look and sound alike. Recall those posts on Charbonnel’s introductory chapters to her book on Jesus being a “midrashic” creation and especially her discussion of the importance of the sounds of Hebrew roots, usually three consonants, and the word-games that could be played with them. (Please allow me to use “midrashic” — in inverted commas — and set aside for now the questions of definition. Some prefer to add the term haggidah to it in this context but that is getting too much of a mouthful/keyboard exercise.)

So here are the key words addressed by Mergui:

mother in law: Hamot = חמות

fever: Hama (also means “sun”; though another word, shemesh, also means “sun”; and cf. Homa = “wall”): = חמה

rebuke: Heima = חמה

gets up/rises: …amod (also means “stand still”) = עמד

Okay. Now for the next bit. Some OT passages where some of those words are key:

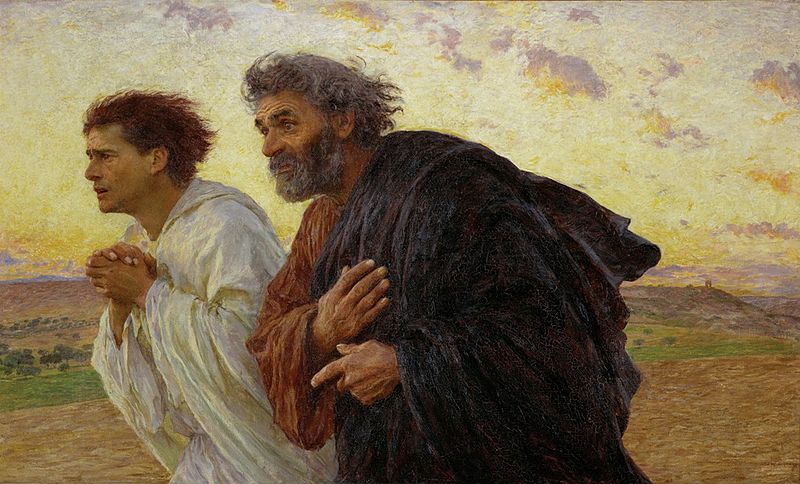

Joshua 10

12 Then Joshua spoke to the Lord in the day when the Lord delivered up the Amorites before the children of Israel, and he said in the sight of Israel:

“Sun, stand still over Gibeon;

And Moon, in the Valley of Aijalon.”

13 So the sun stood still,

And the moon stopped,

Till the people had revenge

Upon their enemies.

Malachi 4

2 But to you who fear My name

The Sun of Righteousness shall arise

With healing in His wings;

There are other passages, too. But we start with those.

What Mergui appears to be proposing is that the Jesus healing Peter’s mother-in-law was inspired by the “revelation” of sounds of the words suggesting that

- the messiah, represented by the sun in the Malachi passage, would heal at a time when the sun is risen (notice that the healing miracle of Jesus is set prior to sunset; notice also that “wings” can mean the fringe of a garment and that we know of another story where a woman was healed by touching the fringe of Jesus’ garment . . . but we wander)

- Joshua, = Jesus, commanded the sun (and note that a synonym forms a word-play with mother-in-law)

- to “stand still” (a word that can also mean “rise up”)

- and the healed mother-in-law set to serving them all; the word for serve, in the Hebrew, apparently is similar to the other word for “sun”, shemesh, and besides, the sun, symbolic of the messiah in Malachi, and in other passages, serves.

But what about the word fever and its sound-alike meaning wall? And not forgetting the word-play that equates the same with mother-in-law.

That brings us to that other famous miracle of Joshua, the way he got the walls of Jericho to come tumbling down. Now in the Bible we need to keep in mind that walls can be sick. Recall the laws on leprosy — “leprosy” can infect a wall (if you know your bible, since I won’t look it up just now.) Further, we read in Ezekiel 13:15 that it is quite reasonable to be angry at a wall. At this point Mergui turns to later rabbinical midrash but I am not clear on the details, not being able to find reasonably quickly an English translation of Exodus Rabbah 50. The interpretation has something to do with the need to return a cloak taken as surety for a loan to its poor owner by sunset. The rabbinic view is that this passage suggests the messiah will come “by/before sunset”. A garment is also a metonymy for the Temple: note the High Priest’s special garment. A rabbinic discussion raises the idea that the Temple walls were destroyed because of the sin of people not returning the garments held as pledges to their poor owners by sunset. So let’s come back to the wall. The rabbis, as I understand Mergui through a glass darkly, argue that repentance will lead God to restore/rebuild/get (back) up the wall that he had once rebuked. Joshua’s miracle reversed, unless you are overly picky about which walls are in question.

The punishment of the exile, it appears, will end with repentance and then the wall will be rebuilt, or “get up” again, by the command of the messiah, presumably.

So you can see why I am frustrated not having a perfectly clear understanding of Mergui’s discussion and not having access to the sources he is addressing. There is much that looks fascinating, perhaps too much so, but certainly enough to make one want to be clear about what is being argued and all its details. And to see what controls there are so we can remove questions over whether one might be able to find any interpretation we want behind a gospel passage.

Like this:

Like Loading...