Throughout the books of the Hebrew Bible (the Christian’s “Old Testament”) one finds assurances for readers that the stories (or histories) being told are detailed in other written sources. Readers are further assured in a number of cases in the books of Kings and Chronicles that even more details can be found in outside sources.

That sounds authoritative. Surely only a “hyper-sceptical” cynic would insist that such source citations were fabricated and the narratives have no credible foundation whatsoever.

But there is a more prudent alternative to having to choose between either/or. We have no independent evidence for the existence of these cited sources but of course that does not mean they never existed.

Are we going a step too far, however, to wonder if they never existed at all and that our biblical authors really did fabricate at least some of them? How could we possibly know?

No, we are not going too far to seriously ponder the question because scholars do have good reasons for believing that in the ancient world historians of the day did indeed sometimes pretend to cite real sources that in fact did not exist.

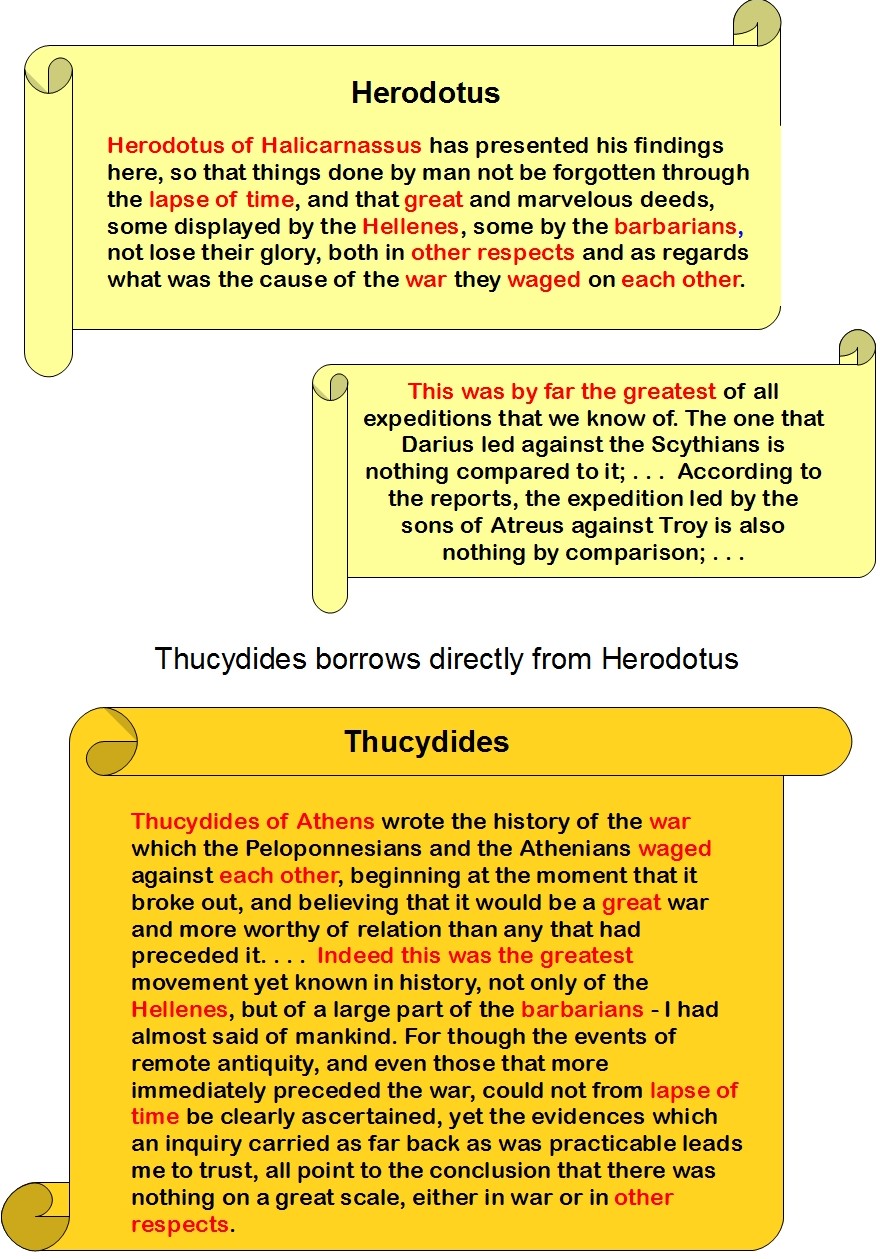

If I begin to set out reasons for suspecting that in some cases the biblical authors were making up sources I run the risk of being accused of having some sort of hostile agenda against the Bible and religion generally. So let’s examine the evidence for other ancient historians fabricating their sources. If we start with the extra-biblical world then we can show that we are analysing the Bible by the same standards we apply to other ancient texts and every reasonable person will happily acknowledge our even-handedness.

One more caveat. Merely identifying grounds for the possibility that source citations are fictions does not mean they “probably” are. What it does mean is that no secure argument or conclusion for a narrative’s reliability can be built upon the presence of source citations.

This post elaborates with a few in depth case-studies on the point I made earlier where I listed examples demonstrating that it was not unusual for ancient historians to fabricate their source-claims.

1. Eyewitness to two monuments of a Pharaoh in Asia Minor

Herodotus writes in his Histories (book 2):

As to the pillars that Sesostris, king of Egypt, set up in the countries, most of them are no longer to be seen. But I myself saw them in the Palestine district of Syria, with the aforesaid writing and the women’s private parts on them.

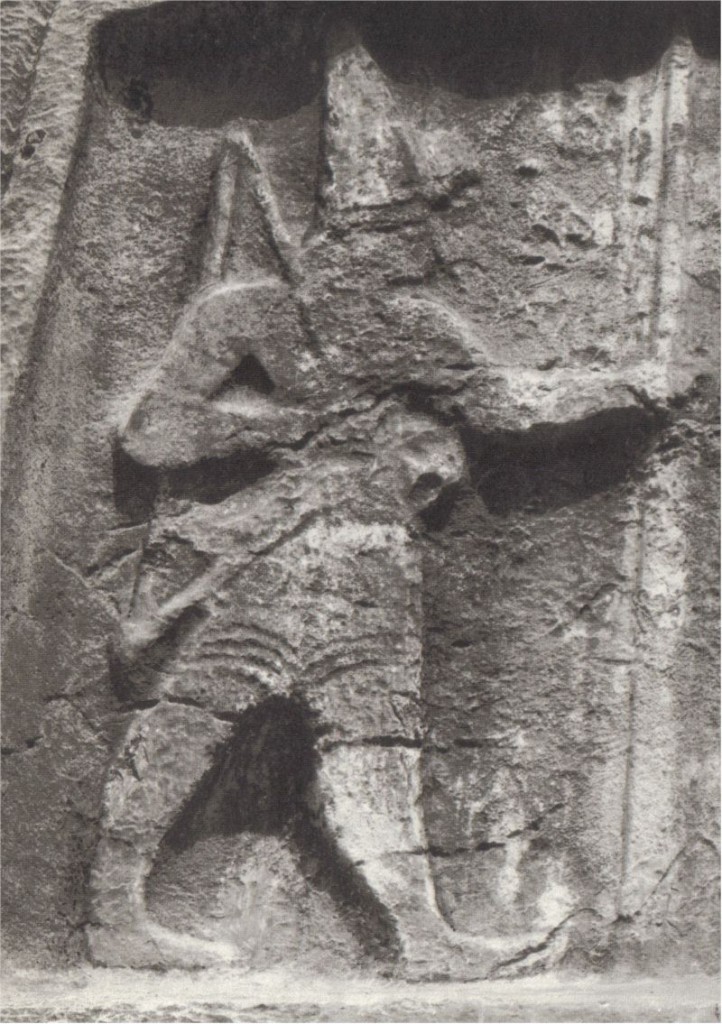

[2] Also, there are in Ionia two figures of this man carved in rock, one on the road from Ephesus to Phocaea, and the other on that from Sardis to Smyrna.

[3] In both places, the figure is over twenty feet high, with a spear in his right hand and a bow in his left, and the rest of his equipment proportional; for it is both Egyptian and Ethiopian;

[4] and right across the breast from one shoulder to the other a text is cut in the Egyptian sacred characters, saying: “I myself won this land with the strength of my shoulders.” There is nothing here to show who he is and whence he comes, but it is shown elsewhere.

[5] Some of those who have seen these figures guess they are Memnon, but they are far indeed from the truth.

There are indeed two statues still to be seen at the Karabel Pass on the old road from Ephesus to Smyrna. Unfortunately for Herodotus’s credibility

- The script on these statues is not Egyptian hieroglyphics but Hittite (“a misstatement that cannot be explained away as a simple error, since to anyone who has seen the former once or twice they are completely unmistakable” – Fehling, p. 135)

- The better preserved of the statues depicts a Hittite war-god, not Sesostris

- The inscription does not run across the shoulders but is set to the right of the head

I have taken the above from Katherine Stott’s Why Did They Write This Way? The main inspiration for this post and the five specific case-studies are based on Stott’s chapter 2 of that book. (I should stress that Stott’s interest is not to suggest fabrication of sources was the general rule.)

Stephanie West in “Herodotus’ Epigraphical Interests” (The Classical Quarterly, Vol. 35, No. 2 (1985), pp. 278-305) writes:

Herodotus here describes the well-known reliefs of the Karabel pass, which depict a Hittite war-god of extremely un-Egyptian appearance. . . .

If Herodotus had seen even a fraction of the Egyptian monuments he claims to have done, he could never have supposed the Karabel reliefs to be Egyptian had he actually visited the site. (West, p. 301)

I like West’s comment on the way illusory way Herodotus so easily persuades readers that he writing an authoritative and reliable account: Continue reading “Ancient Historians Fabricating Sources”