For the meaning of “type 2” mythicism see

two types; for the previous post addressing

Caesar’s Messiah see

Why and

Fishing.

I will post just once more on the mythicist argument in Caesar’s Messiah: the Roman Conspiracy to Invent Jesus. My previous criticism examined the notion that Josephus, when describing one detail of a battle in Galilee, was subtly referring to Jesus call to his disciples to become “fishers of men”. The strongest rebuttal to my argument seemed to be that readers would associate the killing of drowning soldiers with “fishers of men” in the gospels. Atwill responded to explain that it was the parallel sequence of events that was most telling, but my own view is that if the supposed parallel between any event is not valid then it follows that there can be no sequence of events.

So I will follow up with just one more post for the benefit of anyone who might be wondering about the strength of Joseph Atwill’s overall thesis.

In chapter 3, “The Son of Mary Who Was a Passover Sacrifice”, Atwill writes:

While readers can judge this claim for themselves, it should be noted that Josephus wrote during an age in which allegory was regarded as a science. Educated readers were expected to be able to understand another meaning within religious and historical literature. The Apostle Paul, for example, stated that passages from the Hebrew Scriptures were allegories that looked forward to Christ’s birth. I believe that in the following passage Josephus is using allegory to reveal something else about Jesus. (p. 45, my bolding)

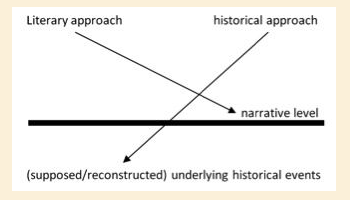

I don’t know of any historical literature in the ancient world that was meant to be read as an allegory. Atwill does not cite any source to verify his assertion that “educated readers were expected to be able to understand another meaning within . . . historical literature”. He does refer to the following passage by Paul, 1 Corinthians 10:1-6 (Young’s Literal Translation), however:

And I do not wish you to be ignorant, brethren, that all our fathers were under the cloud, and all passed through the sea,and all to Moses were baptized in the cloud, and in the sea;and all the same spiritual food did eat, and all the same spiritual drink did drink, for they were drinking of a spiritual rock following them, and the rock was the Christ; but in the most of them God was not well pleased, for they were strewn in the wilderness, and those things became types of us, for our not passionately desiring evil things, as also these did desire.

The Douay-Rheims Bible translates “τύποι” (types) as “figure”:

Now these things were done in a figure of us, that we should not covet evil things as they also coveted.

The Gospel of Mark is sometimes interpreted as an allegorical gospel but those who do interpret its characters and stories as allegories do so on the strength of the following passage, Mark 4:34, in the text itself:

And without parable he did not speak unto them; but apart, he explained all things to his disciples.

This saying has been interpreted as a hint that the entire gospel itself is a parable. Indeed, many of the episodes in Mark’s gospel simply make no sense if read as realistic events. It is impossible for any persons to be as dim-witted as the disciples are depicted in that gospel, for example.

Back to Paul. Paul uses “types” or allegories or figures of speech to explain the covenants. But notably he explains to the readers of his letter that he is speaking in allegories; Galatians 4:24:

These things are being taken figuratively: The women represent two covenants. One covenant is from Mount Sinai and bears children who are to be slaves: This is Hagar.

What we can conclude, then, is that if an author was writing an allegorical scene we can expect him to make it clear to his readers that he is indeed writing allegorically and he explicitly states as much, and warns the reader not to read his account literally.

Conclusion: there are no grounds for thinking that any historian in ancient times, Josephus included, ever wrote allegorically — unless they gave their readers a clear indication that they were doing so. And I don’t know of any historian who ever wrote his account allegorically, period.

It is not the case that “educated readers were expected to be able to understand another meaning within … historical literature.”

Let’s look at the second episode Atwill claims is an allegory of the story of Jesus’ last supper. Continue reading “Type 2 mythicism: one more example”

Like this:

Like Loading...