Here I discuss ancient historians that are cited by M. David Litwa as part of his attempt to demonstrate that our canonical gospels conformed to a popular type of historical writing that included “fantastical elements”. (I will discuss Litwa’s comments on these ancient authors in a future post and refer readers back to this post.)

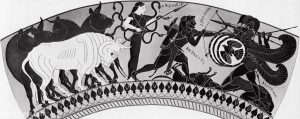

Diodorus Siculus

Diodorus Siculus (= of Sicily) belonged to the first century BCE. In Book 4 of his Library of History he informed readers that he would have to rely upon “writers of myths” for his account of the life of Heracles.

[W]e shall . . . relate his deeds from the beginning, basing our account on those of the most ancient poets and writers of myths. This, then, is the story as it has been given us . . . . .

(Book 4.8-9)

So was Diodorus blending myth and history here? Not really. Earlier Diodorus listed four reasons why myth was not genuine history:

For, in the first place,

- the antiquity of the events they have to record, since it makes record difficult, is a cause of much perplexity to those who would compose an account of them;

- and again, inasmuch as any pronouncement they may make of the dates of events does not admit of the strictest kind of proof or disproof, a feeling of contempt for the narration is aroused in the mind of those who read it;

- furthermore, the variety and the multitude of the heroes, demi-gods, and men in general whose genealogies – must be set down make their recital a difficult thing to achieve ;

- but the greatest and most disconcerting obstacle of all consists in the fact that those who have recorded the deeds and myths of the earliest times are in disagreement among themselves.

For these reasons the writers of greatest reputation among the later historians have stood aloof from the narration of the ancient mythology because of its difficulty, and have undertaken to record only the more recent events.

(Book 4.1.1-4. Formatting and bolding is mine in all quotations)

So why does Diodorus admit to using mythical sources for his biographical account of Heracles?

Diodorus uses mythical material but at the same time he clearly distinguishes it from the rest of his historical narrative. Mythical sources might be all he has for Heracles but Diodorus relates them in a way that indicates he is critically removed from the content. The reader can see immediately Diodorus’s change in rhetoric and understand that what he or she is reading is something Diodorus is merely passing on “for what it’s worth”.

Footnote 50 is a brief citation that leads us to a passage in another work that I will quote in full here.

Diodorus maintains a careful narrative manner both in his accounts of the Greek gods in Book IV and more generally in the first six books as a whole: long passages are given in indirect discourse governed by ‘they say’, ‘it is said’, ‘the myth writers say’, and the like. Such a manner shows Diodorus to be maintaining a critical distance (like Herodotus’ manner in his Book II) from what he relates; and although he does not usually call into question the material that he narrates, he nevertheless shows himself aware of the different nature of this material by a different and distancing narrative style; no other section of the preserved portions of the Library reveals the same narrative manner.

(Marincola, 121)

But, as the passages noted above show, Diodorus realizes that myth cannot be approached in the same fashion as history, and that a degree of uncertainty needs to be accepted about mythical tales. Occasionally he reminds his readers of this: “in general the ancient myths do not give a simple and consistent account; therefore it is no wonder if we should come across some ancient accounts which do not agree among all the poets and historians” (. . . 4.44.5–6). Accordingly, Diodorus is very careful throughout the first five books, and presumably in the lost sixth book, to indicate what he considers to be mythical material. In the process he also grapples with the problem of where “history” begins and myth ends in a universal history. When he wants to mark off a narrative as mythical, he places it in indirect discourse and introduces it with a verb, frequently μυθολογεῖν without a subject.50 This is especially important in the first three books, which mix “mythical” narratives with the ethnography and legitimate early history of “barbarians.” For example, at 1.9.6, as he begins the account of the Egyptian gods, he justifies his decision to start with Egypt on the grounds that “the genesis of the gods is said in myth to be in Egypt” (. . . 1.9.6). The Egyptian theogony that follows is then given in indirect discourse through chapter 29. In contrast, the historical narrative of the Egyptian kings (1.45–68) is given primarily in direct discourse.

(Muntz, 105-106)

To illustrate:

The beginning of the account based on mythical accounts (1.9 ff)

9. And since Egypt is the country where mythology places the origin of the gods, where the earliest observations of the stars are said to have been made, and where, furthermore, many noteworthy deeds of great men are recorded, we shall begin our history with the events connected with Egypt.

10. Now the Egyptians have an account like this: When in the beginning the universe came into being, men first came into existence in Egypt . . .11. Now the men of Egypt, they say, when ages ago they came into existence, as they looked up at the firmament and were struck with both awe and wonder at the nature of the universe, conceived that two gods were both eternal and first, namely, the sun and the moon, whom they called respectively Osiris and Isis,” . . .

12 . . . And they say that the most renowned of the Greek poets1 also agrees with this . . .

13. And besides these there are other gods, they say, who were terrestrial, . . .

14. Osiris was the first, they record, to make man-kind give up cannibalism . . .

Similarly for the history in Book 4 of Heracles:

9. This, then, is the story as it has been given us . . . .

Compare the beginning of the historical narrative (1.45, 68) Continue reading “The Relationship between Myth and History among Ancient Authors”