The creation account in Genesis 1 is unlike other creation myths from the ancient world.

There are little hints in the chapter that the author was aware of more dramatic myths of gods fighting monsters and in the process creating the cosmos, but unlike those myths Genesis 1:1-2:3 appears to be . . .

. . . a radical purification and distillation of all mythical and speculative elements, an amazing theological accomplishment!

This account of creation is unique in this respect among the cosmogonies of other religions. . . . But the atmosphere of Gen., ch. 1, is not primarily one of reverence, awe, or gratitude, but one of theological reflection. . . . But just this renunciation also mediates aesthetically the impression of restrained power and lapidary greatness. (Rad 1972, 64)

In an earlier edition of his commentary Gerhard von Rad skirted along the sides of Russell Gmirkin’s thesis:

Ionic refers to one of the four Greek tribes: Ionians, Dorians, Achaeans, Aeolians

Natural philosophy: theories about the natural world, nature

Cosmogony: theories on the origin of the universe

Theogony: Account of the origin of the gods

Theomachy: Account of war among gods

One can speak . . . only in a very limited sense of a dependence of this account of creation on extra-Israelite myths. Doubtless there are some terms which obviously were common to ancient Oriental, cosmological thought; but even they are so theologically filtered . . . that scarcely more than the word itself is left in common. Considering [the author’s] superior spiritual maturity, we may be certain that terms which did not correspond to his ideas of faith could be effortlessly avoided or recoined. What does the term “tehōm” (the “deep”) in v. 2, the word for the unformed abysmal element of creation, still have in common with the mythically objective world dragon, Tiamat, in the Babylonian creation epic? Genesis, ch. 1, does not know the struggle of two personified cosmic primordial principles; not even a trace of one hostile to God can be detected! The tehōm has no power of its own; one cannot speak of it at all as though it existed for itself alone, but it exists for faith only with reference to God’s creative will, which is superior to it. In our chapter this careful distillation of everything mythological (but only this) reminds one of the sober reflections of the Ionic natural philosophers. (Rad 1961, 63)

But Rad was writing from the conventional perspective that what we read in Genesis was the product of centuries of thought, writing and re-writing. Rad seemed to think that his 1961 reference to the Ionic natural philosophers was even a potential distraction so he dropped it in the revised edition. For Gmirkin [RG] the Ionic philosophers were indeed the key to understanding why the creation account of Genesis is, as Rad observed, “unique”. But that possibility, as we noted in the previous post, has not entered into the discussion as a possibility until now.

Before addressing those “sober reflections of the Ionic natural philosophers” RG explores the different types of cosmogonies that the people of Israel surely knew about from their neighbours. His text is packed with details and references. It is not a quick, light, read. Ideas set out in one place reappear in support of a more comprehensive view later in the chapter. Fortunately, I am the kind of reader who appreciates more detail rather than less and recontextualized repetitions rather than dangerous shortcuts. To address the key ideas here, though, I need to stand back and rethink and distil all that I have read. (That’s part of my excuse for not posting sooner. Another reason is that I have been sidetracked with other books that have newly arrived on loan and in the post.)

Creation Myths

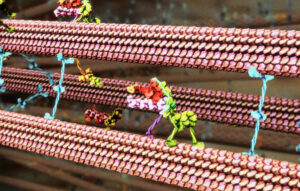

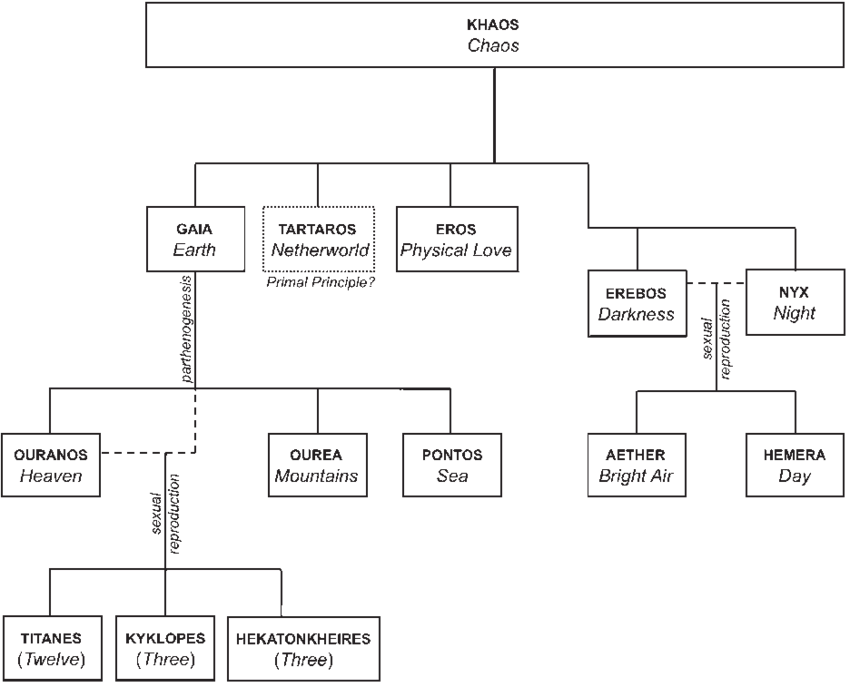

RG begins his survey of ancient creation myths with theogonies. The famous Greek one is Hesiod’s Theogony. The first god was Chaos and from Chaos was “born” Gaia or Earth, and so forth. You can see how it goes from a diagram I have borrowed from Karen Sonik‘s publication:

RG discusses the comparable anthropomorphisms of Babylonian and Canaanite gods. Those cultures have left us no comparable theogonies, however. Of particular interest, of course, is that for the Greeks it all began with Chaos: we are aware of a similar origin in the opening words of Genesis.

A better-known class of myths are the theomachies. The Titan Kronos (the Roman Saturn) castrates Ouranos and inaugurates a new (golden) age in which humankind was created; later Zeus led his supporters in a war against Kronos and the other Titans; each successive event introducing a new era. But these Greek “wars of the gods” were not related to the creation of the cosmos. For that we turn to the Babylonian story of Marduk killing the sea monster Tiamat, cutting her body apart and using it to form the sky and earth – and from her blood creating the first humans who also incorporated some divine element from the slain god. Tiamat reminds us of the Hebrew word for deep as we saw in Rad’s quotation above. RG also draws our attention to further instances of overlaps with Genesis – Marduk being interpreted as light and wind which he used as weapons against Tiamat.

All of the above is far from the kind of creation narrative we read in Genesis 1.

When we come closer to our home of special interest, Canaan, we finally encounter stories that have surfaced to some extent in the Bible, but not in Genesis. Continue reading “Genesis 1 “Amazing” “Unique” — [Biblical Creation Accounts/Plato’s Timaeus – 2]”