Passages that for modern fundamentalist readers refer doctrinally to Jesus’ death and some imaginary “end time” in some indefinite future:

Passages that for modern fundamentalist readers refer doctrinally to Jesus’ death and some imaginary “end time” in some indefinite future:

Luke 12:49-53

49 I came to cast fire upon the earth; and what do I desire, if it is already kindled?

50 But I have a baptism to be baptized with; and how am I straitened till it be accomplished

51 Think ye that I am come to give peace in the earth? I tell you, Nay; but rather division:

52 for there shall be from henceforth five in one house divided, three against two, and two against three

53 They shall be divided, father against son, and son against father; mother against daughter, and daughter against her mother; mother in law against her daughter in law, and daughter in law against her mother in law.

Luke 21:23

23 Woe unto them that are with child and to them that give suck in those days! for there shall be great distress upon the land, and wrath unto this people.

Luke 23:28-30

28 But Jesus turning unto them said, Daughters of Jerusalem, weep not for me, but weep for yourselves, and for your children.

29 For behold, the days are coming, in which they shall say, Blessed are the barren, and the wombs that never bare, and the breasts that never gave suck

30 Then shall they begin to say to the mountains, Fall on us; and to the hills, Cover us.

Luke 21:6

6 As for these things which ye behold, the days will come, in which there shall not be left here one stone upon another, that shall not be thrown down.

Luke 21:20

20 But when ye see Jerusalem compassed with armies, then know that her desolation is at hand.

Luke 21:24-27

24 And they shall fall by the edge of the sword, and shall be led captive into all the nations: and Jerusalem shall be trodden down of the Gentiles, until the times of the Gentiles be fulfilled.

25 And there shall be signs in sun and moon and stars; and upon the earth distress of nations, in perplexity for the roaring of the sea and the billows

26 men fainting for fear, and for expectation of the things which are coming on the world: for the powers of the heavens shall be shaken.

27 And then shall they see the Son of man coming in a cloud with power and great glory.

Luke 17:33-37

33 Whosoever shall seek to gain his life shall lose it: but whosoever shall lose his life shall preserve it.

34 I say unto you, In that night there shall be two men on one bed; the one shall be taken, and the other shall be left.

35 There shall be two women grinding together; the one shall be taken, and the other shall be left.

36 There shall be two men in the field; the one shall be taken, and the other shall be left

37 And they answering say unto him, Where, Lord? And he said unto them, Where the body is, thither will the eagles also be gathered together..

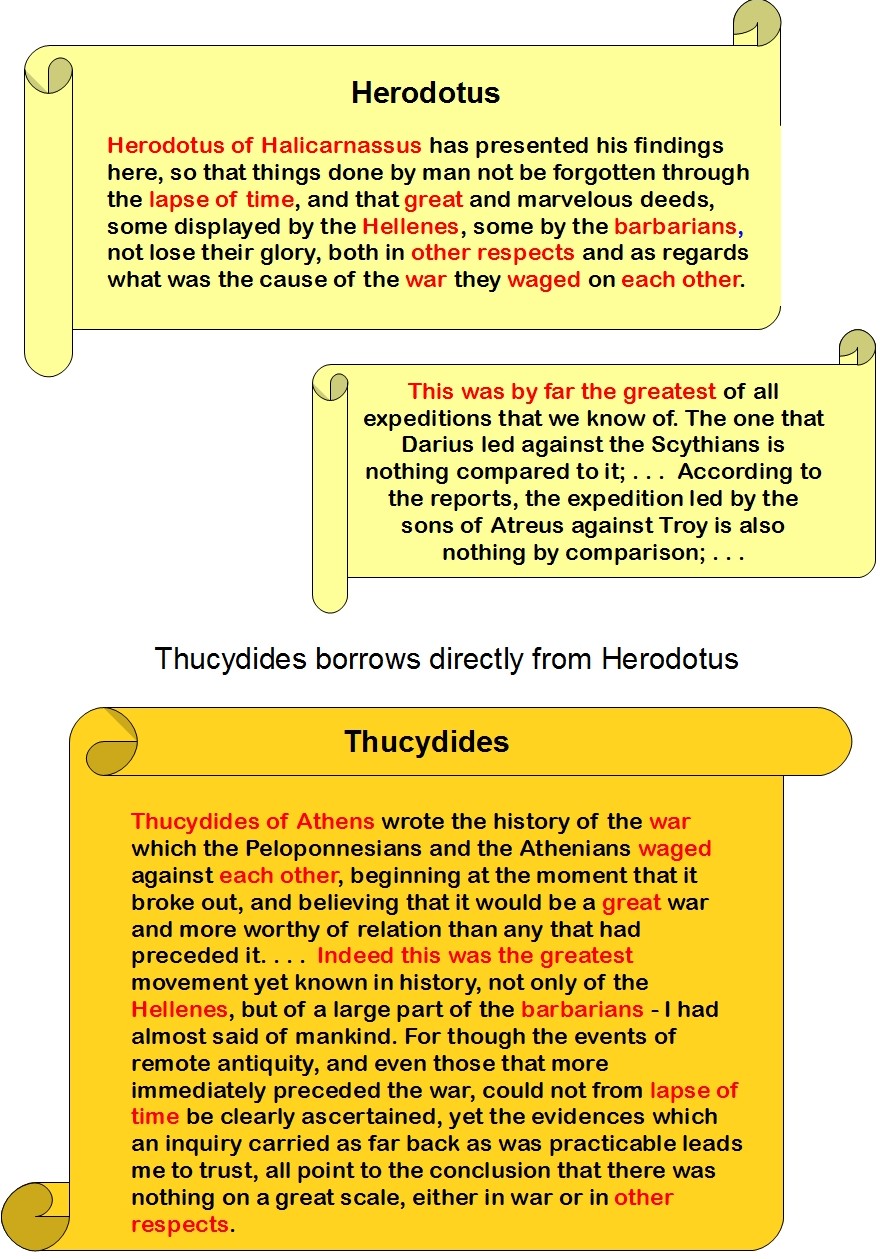

The Literary Form of the Gospels

Much depends on our analysis of the literary form of the gospels. If we conclude on the basis of Gospel passages like those above that the gospels are novella-like apocalypses or apocalyptic prophecies, a variant of writings like Daniel, then by definition they are written with reference to historical events known to their original audience.

When the above passages are read with the knowledge of those events, the war with Rome and the destruction of Jerusalem, then they refer both to the death of Jesus and the catastrophic fate of Jerusalem.

Thus a proper understanding of literary form gives us a historical meaning. (Clarke W. Owens Son of Yahweh: The Gospels as Novels) Continue reading “Constructing Jesus and the Gospels: Apocalyptic Prophecy”