The letters of Paul that are understood to have been written some twenty to ten years before the fall of Jerusalem in 70 CE speak about the crucifixion of Jesus as a simple fact. There is never any elaboration of when or where it happened (unless one treats 1 Thess 2:13-16 as genuine). The message of death and resurrection of the son of God by itself is sufficient to lead to conversion. For Mark, though (and for the sake of convenience and convention I’ll call the author of the second gospel Mark), this was not enough. A detailed story involving betrayal, abandonment, a trial, physical abuse and crucifixion with attendant miracles had to be told. I side with those critical scholars who conclude that all of those details are fabrications since the narrative was created out of various passages in the “Old Testament” and none of Jesus’ followers could have witnessed anything that happened once he was in the hands of the Jewish priests and Roman guards. But even if we concede for the sake of argument that the Passion account of Jesus did hold some “historical core” at its base, there can be no denying that the way Mark has shaped the story with its many allusions to OT scriptures is his own creative work.

Why? Why did he write that narrative and why did he write it the way he did?

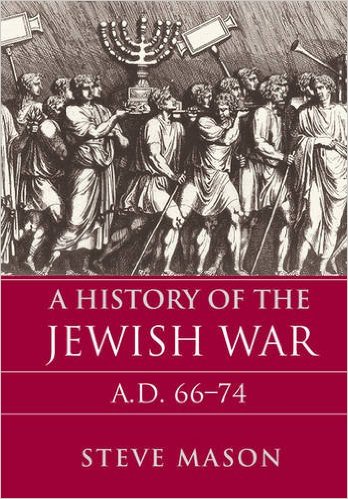

Some years back I wrote a series about Son of Yahweh: The Gospels as Novels, by Clarke Owens. Clarke Owens was analysing the Gospel of Mark from the perspective of a literary critic and argued that it was necessary to see the gospel as a product of its time, and that time was in the wake of the Jewish War that condemned untold numbers of Jewish victims to crucifixion around the city of Jerusalem.

In the past few months I have caught up with another work, or two of them, by a German New Testament scholar who makes much the same argument from his perspective:

In the past few months I have caught up with another work, or two of them, by a German New Testament scholar who makes much the same argument from his perspective:

- Bedenbender, Andreas. Frohe Botschaft am Abgrund: Das Markusevangelium und der Jüdische Krieg [= Good News at/from the Abyss: The Gospel of Mark and the Jewish War]. Leipzig: Evangelische Verlagsanstalt, 2013.

- Bedenbender, Andreas. Der Gescheiterte Messias [= The Failed Messiah]. Leipzig: Evangelische Verlagsanstalt, 2019.

Andreas Bedenbender’s view is that the author of the earliest gospel was writing from a place of trauma and was struggling to come to terms with the fate of his people that he had just witnessed. Had not the gospel being preached about Jesus promised the soon-to-arrive Kingdom of God? Now this!? By a “failed messiah” he means a messiah who failed in the same sense that the OT prophets had failed when they preached their warnings about Assyrian and Babylonian captivity if the people of the northern and southern kingdoms did not mend their ways. This position of trauma, Bedenbender believes, explains the dark and confronting features and outright contradictions in the gospel: a messiah who now does, now does not, seem to care for his people, such as when he heals them at one moment but deserts them when they are trying to find him; who terrifies rather than comforts others by wielding his power over demons and the elements; who like a ghost is seen walking on water past his disciples instead of rushing to help them in their distress; who condemns his disciples for an unnatural blindness that they cannot help; who orders silence when a crowd has just heard and witnessed all; and whose story closes with the only witnesses to news of his resurrection fleeing dumb with fear (the earliest manuscripts of the gospel conclude at Mark 16:8).

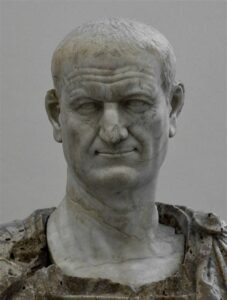

For Bedenbender the crucifixion of Jesus is a kind of allegory of the fate of Jerusalem. The messiah is made to share in the fate of the Jewish people. From the Jewish historian Josephus we learn that those who did not die from starvation or factional violence or the slaughter of the advancing Roman soldiers or who were not enslaved were crucified:

Scourged and subjected before death to every torture, they were finally crucified in view of the wall. . . . The soldiers themselves through rage and bitterness nailed up their victims in various attitudes as a grim joke, till owing to the vast numbers there was no room for the crosses, and no crosses for the bodies. (Josephus, Jewish War, Book 6: 449-451 – G.A. Williamson translation)

We saw a similar argument in the series on Nanine Charbonnel’s Jésus-Christ, sublime figure de papier. The Gospels created the figure of Jesus in part as a personification of the people of Israel.

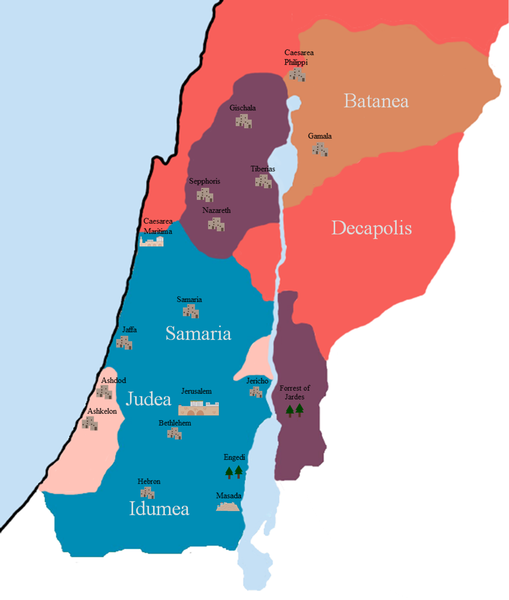

Bedenbender goes beyond the events of the crucifixion, though. Right from the beginning of the gospel, we read of “a wilderness place” that is the frequent abode of Jesus. It is easy enough to relate the “wilderness” image to other wilderness scenes in the OT, most especially the “wilderness” through which Moses led the Israelites for 40 years. But Mark repeatedly refers to a “wilderness place” — έρημος τόπος = erēmos topos — and that brings to the minds of readers of the Greek translation (the Septuagint) of Jeremiah, Daniel and the Psalms the desolate ruin of God’s “place”, Zion and where the Temple had once stood. This is one of the ways in which the Jewish War is woven into the Gospel of Mark from its opening chapter.

Place names and names of persons are related to scenes and leaders that became well-known in the Jewish War of 66 to 70/73 CE. In the OT women are very often personifications of nations and cities and Bedenbender identifies the same figurative tradition in the names of Salome, Jairus’ daughter, Mary Magdalene (Magdala is another name for Tarichea, the scene of one of the bloodiest slaughters of Jews described by Josephus) and the others. Simon, of course, is probably the most prominent name in the gospel and here Bedenbender suggests that we see in this figure an encapsulation of the Jewish rebel movement from its beginning with Simon Maccabee through to Simon bar Giora. Simon Maccabee’s son Alexander became famous for his enforced Judaizations and mass crucifixions of his Jewish enemies, and the names of Tiberius Alexander and Rufus are readily associated with the Roman military confronting Jerusalem. (I can’t help wondering — I know this must seem outlandish to many who have more conservative views of Simon of Cyrene, father of Alexander and Rufus, who carried Jesus’ cross — that the Gospel of Mark could have been written as late as the second century in the wake of horrendous Jewish rebellions in Cyrene and when yet another Simon, with the support of a rabbi “James”, defied Rome. The result of that rebellion in the days of Hadrian really was the ultimate end to Jerusalem and any hopes for a rebuilt temple. Would not that timeline place the author far closer to catastrophic events with a greater likelihood of writing in a pall of trauma than if he had been writing a few years after the events of 70?)

Andreas Bedenbender begins with a study of the meaning of allegory and related literary devices and examines why we should think of the entire narrative, and not merely isolated scenes, as containing a reference to the fate of Judea and what that meant for those who believed in Jesus as their messiah. He analyses the narrative to demonstrate, I think successfully, that not only the parable sayings but the miracles themselves are symbolic and take on a special depth of meaning when read in the context of the war. I believe we can go beyond the miracles and understand other narrative features (beginning with the baptism and call of the first disciples) as rich in “allegorical” references. Bedenbender has an interesting interpretation of Jesus’ debating confrontations with the Pharisees, Herodians, Sadducees and scribes after his entry into Jerusalem that focuses on Jesus’ attempt to disabuse them (and readers) of any notion of a messiah who was destined to wage a physical war against earthly opponents.

I look forward to posting more details about these works. In the meantime, I cannot ignore my resolution to address Witulski’s case for a Hadrian-era date for the Book of Revelation; and someone else has recently reminded me that I have yet to finish a series I was doing back in 2018 on the Parables of Enoch and the Jewish concept of a heavenly messiah.

And as Tim pointed out in his latest post, more needs to be said about “the insidious nature of agnotology” that poses a potential threat to our futures. We have to remain optimistic if we are to take the necessary actions and I think there are many reasons to be optimistic: look at what these ninth–graders can do! — this and this!