In a former life I was mixed up with British Israelism (the belief that the Anglo-Saxon races are the “lost ten tribes of Israel”) so recently I was interested to find a new research paper by J. M. Berger using British Israelism as a case study in how an innocuous if eccentric belief system was able to evolve into today’s antisemitic white supremacist Christian Identity movement. (I have posted details of Berger’s paper at the end of this post.)

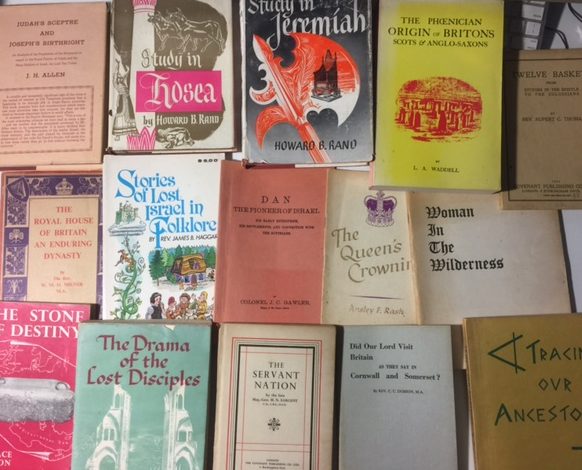

The church I once belonged to embraced British Israelism as one of its core doctrines. When I wanted to learn more about the details of this belief-system I tracked down an old book-lined room of old wooden desks and chairs and tended by an old man representing what appeared to be the last gasping remnant of the “British Israel Association” in Brisbane, Queensland, Australia. I purchased some very old literature with quaint titles that I still have with me:

Most of those publications hold a special place for Jews: the Anglo-Saxon nations (British and American) may have been declared the descendants of the tribe of Joseph but the British royal family was esteemed as a branch of the Davidic dynasty. The tribe of Judah, the Jews, were welcomed as inheritors of the promise of “the sceptre” that would continue unbroken until the coming of the Messiah.

So how could such a belief system evolve into a racist, even a violent, outfit?

It is impossible to cover the details of Berger’s discussion here but I can hit a few highlights. (This post does not do justice to Berger’s theoretical argument.)

It will be helpful to understand some basic principles of British Israelism.

Of primary importance is the distinction between the terms Israel and Jew. Israel is said to refer primarily to the ten tribes who made up the Bible’s kingdom of the north, based at Samaria, while the term Judah, from which we have Jews, was the name of the southern kingdom with its royal city of Jerusalem. Thus Israel refers to the northern ten tribes, the kingdom conquered by Assyria in the 720s, while the Jews belonged to the southern kingdom up to the time of the Babylonian captivity.

The promises made to Abraham were primarily racial or national. Yes, grace was promised (through Christ) but so was race. Multitudes of progeny, many nations and kings, dominance of the political landscape and super-abundant possession of wealth were promised Abraham’s descendants. Those promises became more specific when the dying Jacob passed on blessings to his sons, assigning each one, a future tribe, a particular destiny. The eldest son of Joseph was Ephraim and his descendants were to become a “multitude of nations” while his brother, Manasseh, was to become “a great nation”.

According to the argument these promises were never literally fulfilled in Bible times.

But around the mid-nineteenth century a few people did see two brother peoples, one a multitude of nations and the other a great nation, who did possess all the wealth and military dominance that they believed had been promised to Abraham’s descendants, specifically to the two sons of Joseph: the promises to Ephraim were seen fulfilled in the British Commonwealth of Nations and those to Manasseh in the United States of America.

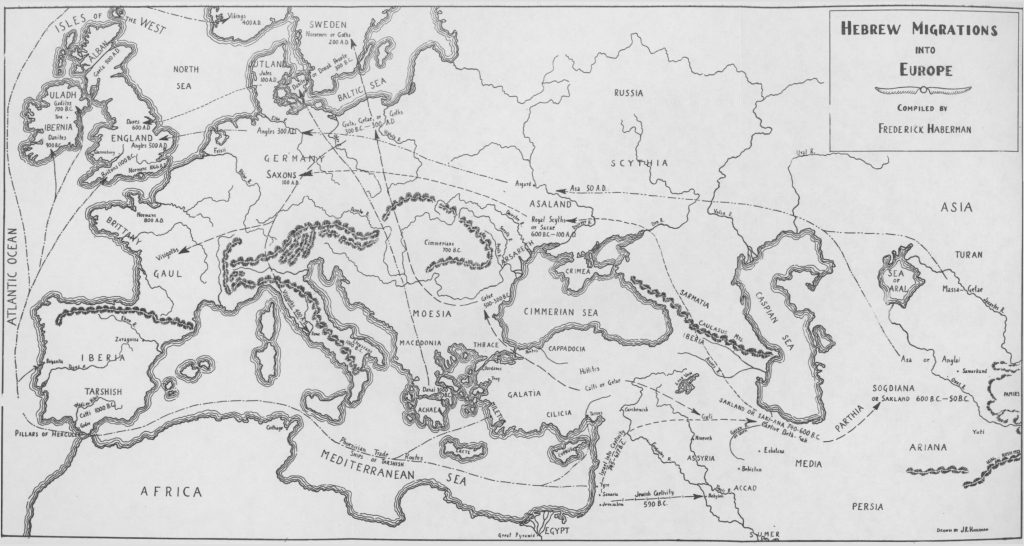

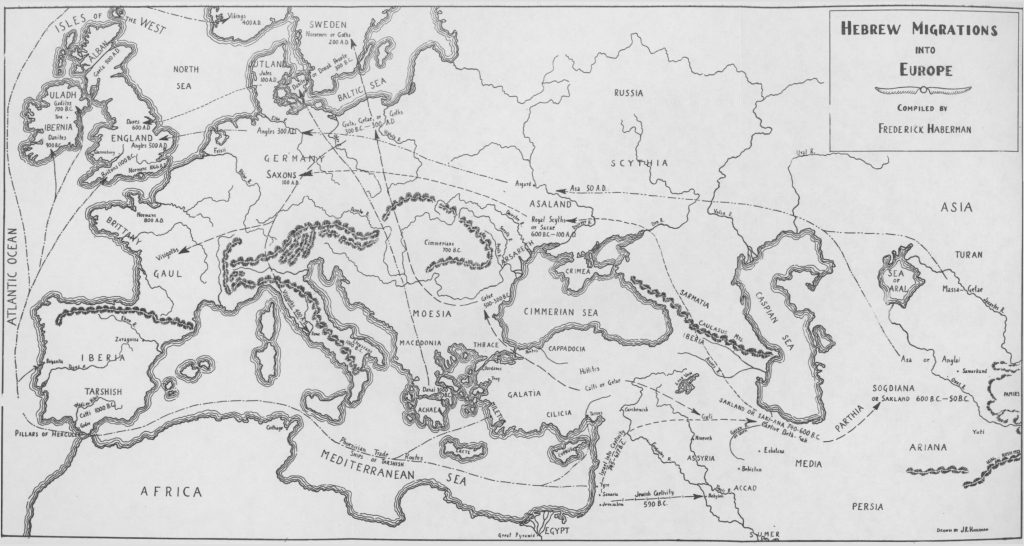

After ancient Israel (the northern ten tribes) were taken into captivity they eventually migrated (as prophesied) to the north and the west, reaching the British Isles, Scandinavia, the Low Countries, northern France.

But none of this was antisemitic. Quite the contrary, as Berger rightly notes, it was philo-Semitic. British Israelism had a place for all the tribes of Israel: the Jews had been promised not national wealth but a perpetual royal dynasty. Luckily the prophet Jeremiah was able to rescue some of the royal daughters (descended from David) at the time the Babylonian king Nebuchadnezzar was ravaging his way through Jerusalem and eventually relocate them in Ireland where they united with another branch of Judah’s royal family line.

In the last days the British royal family would belatedly acknowledge their true identity and hand their throne over to Jesus at his return. The British and American nations would recognize at last that they were Israelites and Jews would convert to Christianity and everyone would live happily ever after.

The

earliest copy of John Wilson’s formal ideological statement of British Israelism dates from 1850, although a Preface the

1876 edition is dated 1840.

So that was British Israelism as it was known for around 100 or so years — up to the time of the Second World War. Bizarre, yes, but surely harmless.

There was a tiny seed, however, that some generations after its publication (see insert on John Wilson) was coopted for lunatic and violent ends. That seed was the passing claim that all of today’s races descended from the three sons of Noah, with those from Ham being the children of the curse. (Ham, recall, was cursed by Noah for apparently taking advantage of his drunken stupor.)

Yet the fact that the Jews were designated a place apart from certain other tribes of Israel would eventually prove to be a wedge that could too easily be exploited in an increasingly anti-Semitic environment. Notice the following lonely paragraph penned by John Wilson in his Lectures on our Israelitish origin (1876 edition):

We have adverted to the case of the other house of Israel, which as being left in the land, and having generally borne the name of “Jews,” are supposed to have remained distinct from all other people. We have seen that the best portion of them must have become mingled among the Gentiles; and the worst of the Gentiles—the Canaanites and Edomites, children emphatically of the curse—having become one with them, they have become guilty of the sins of both, the curse of which they have been enduring ; that they have nothing in the flesh whereof to boast, and cannot obtain possession of the land by the old covenant ; that they can only obtain a peaceable settlement as being viewed in the One Seed Christ, and as being joined to the multitudinous seed to come, especially of Ephraim. (p. 368)

Ominous. But a reflection of the times. The descendants of Shem, Noah’s eldest son, wrote Wilson, had “the greatest natural capacity for [religious] knowledge” (p. 28) and it is from them that the tribes of Israel and the “other white races” descended. Wilson even uses the “Semitic” to refer to all of these descendants of Shem, not only the Jews.

Rising tide of anti-Semitism

Continue reading “How Philo-Semitic British Israelism Morphed into Anti-Semitic White Supremacism / Christian Identity”

Like this:

Like Loading...