The only thing new in the world is the history you don’t know.

–Harry S. Truman

You have to start somewhere. That’s a distinct problem. How do we go about learning a subject as vast as biblical studies or biblical history? We could dive right in with some of the classics of text and form criticism, but we probably won’t fully understand them, because we don’t have the proper foundations.

Some of you may have taken survey courses at university in world history or American (or whatever your native country might happen to be) history. These courses tend to serve two purposes. First, they provide a means for students majoring in other studies to have some sort of foundation in “how we got here.” Second, they serve as a jumping-off point for those of us who continue on to our degrees in history.

Learning and unlearning

Every historian (amateur and professional) in America knows or at least should know our dirty little secret: that freshman history students face a serious disadvantage, because they must unlearn most of what they learned in high school. They must clear away the happy, feel-good history in which we are always the good guys and everything turns out well in the end. Imagine, for a moment, that you had learned medieval alchemy in high school only to discover in Chemistry 101 at your university that you don’t have the slightest idea what they’re talking about.

Survey courses in biblical studies or NT studies in some universities purport to do the same sort of thing. That is, they expose students to another way of thinking about the Bible other than what they learned in Sunday School. I took such a class in 1978 at Ohio University, and in many ways, I would consider it a positive experience. However, I would later discover that much of what I had accepted as bedrock could not stand up to stronger scrutiny.

I admit that my work in history in the mid-1980s at the University of Maryland should have alerted me to the obvious problems with biblical studies. However, it took the work of the so-called minimalists to push me in the right direction. I stumbled onto Thomas Thompson’s The Mythic Past completely by accident while wandering around a Barnes and Noble somewhere in Atlanta. (My job took me on frequent road trips back in the ’90s and the aughts.) The book (in hardback) apparently had not sold well, and they marked it down significantly. Lucky me.

Reading and rereading

Thompson asked questions I had never considered. It soon became clear that I had never asked these sorts of questions, because I had been properly trained not to. Beyond that, American education generally favors the notion of “moderation” as a virtue in and of itself. Surely only an extremist would question the historicity of Moses or Solomon. And extremism in the pursuit of anything is a vice. Surely.

Despite my proper training, one simple question — “How do we know?” — began to gnaw at me, the way a steady drip wears away stone. For me, Thompson more than anyone else gave me permission (so to speak) to ask even more dangerous questions. However, it took me longer to get up to speed with Philip R. Davies. (See Neil’s tribute to the late, great scholar here.)

For example, I had started In Search of Ancient Israel but never finished it until this past summer. Longtime Vridar readers will recall that Davies, and especially this book had a huge impact on Neil. You can find much more detail about this work over at the vridar.info site. For more related posts here on vridar.org, follow the tags above. (Below, I’ll be referring to the second edition of this work.) Continue reading “Rereading Literature and History — Some Thoughts on Philip R. Davies”

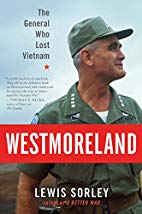

A few weeks ago, I was dealing with a mold issue in our RV’s bathroom. (Note: If you see mushrooms growing out of a crack in the wall, it’s usually a bad sign.) Having resigned myself to working with gloves, wearing a mask, sitting uncomfortably on the floor for at least an hour, I resolved to find a long audio program on YouTube and let it play while I worked. I happened upon a presentation by Dr. Lewis Sorley, based mainly on his book,

A few weeks ago, I was dealing with a mold issue in our RV’s bathroom. (Note: If you see mushrooms growing out of a crack in the wall, it’s usually a bad sign.) Having resigned myself to working with gloves, wearing a mask, sitting uncomfortably on the floor for at least an hour, I resolved to find a long audio program on YouTube and let it play while I worked. I happened upon a presentation by Dr. Lewis Sorley, based mainly on his book,