The Gospels of Matthew and Luke contain best-known birth narratives of Jesus but they have mystified many inquiring minds who wonder how they can be so totally different from each other. They are so different that many scholars cannot accept that Luke had ever read Matthew’s account: they had to be derived ultimately (and independently) from some remote common source.

Here’s what they do have in common (from a list by Raymond Brown in The Birth of the Messiah):

1. The parents are called Mary and Joseph, are engaged or married, but do not yet live together at the time of Jesus’ conception;

2. Joseph is a descendant of David;

3. an angel announces the future birth of Jesus, although this announcement is addressed to Joseph in Matthew, but to Mary in Luke;

4. Mary had the child without intercourse with Joseph;

5. conception takes place through the work of the Holy Spirit;

6. the angel prescribes that the child should be called Jesus;

7. an angel declares that Jesus will be the Saviour:

8. the child is born after the parents start living together;

9. the birth takes place in Bethlehem:

10. it is temporally connected to the realm of Herod the Great;

11. the child grows up in Nazareth.

Yet the two stories are quite simply incompatible. In Matthew the infant Jesus is taken to Egypt to escape the “massacre of the innocents” after Herod learned from the magi of the birth of a “future king”; in Luke there is no threat to Jesus’ life, shepherds worship the newborn, he is presented at the Temple, and so forth. (I happen to think it quite possible that Luke did know Matthew’s birth narrative but that is ultimately irrelevant to the main point of this post.)

Though these two canonical stories are the best known they are not the only early Christian narratives of Jesus’ birth. We also have the Infancy Gospel of James. Here we read that Mary gave birth in a cave and a midwife confirms Mary’s virginity immediately after the birth. Jesus’ step-brother James is presented as the narrator of that account. Then there’s the Ascension of Isaiah where we read that Jesus simply appears (without any angelic warnings to either parent) as if by magic in front of Mary who is in her house, and Mary’s belly is restored to normal and she appears to be left wondering “what happened?”

Further, there are other writings from as early as the second century that mention other details not found in any of our narratives that are believed to have been prophesied about the birth of Jesus. So in the Acts of Peter we read Peter declaring all sorts of proofs to Simon Magus that Jesus’ birth was surely prophesied in many ways in the Scriptures and other now-lost writings:

XXIV. But Peter said: Anathema upon thy words against (or in) Christ! Presumest thou to speak thus, whereas

the prophet saith of him: Who shall declare his generation? [or, His family, who will tell it?] — [Isa. 53:8]

And another prophet saith: And we saw him and he had no beauty nor comeliness. — [Isa. 53:2]

And: In the last times shall a child be born of the Holy Ghost: his mother knoweth not a man, neither doth any man say that he is his father. — [?]

And again he saith: She hath brought forth and not brought forth. — [From the apocryphal Ezekiel (lost)]

And again: Is it a small thing for you to weary men (lit. Is it a small thing that ye make a contest for men) — [?]

[And again:] Behold, a virgin shall conceive in the womb. — [Isa. 7:13f]

And another prophet saith, honouring the Father: Neither did we hear her voice, neither did a midwife come in. — [From the Ascension of Isaiah, xi. 14]

Another prophet saith: Born not of the womb of a woman, but from a heavenly place came he down. — [?]

And: A stone was cut out without hands, and smote all the kingdoms. — [Dan. 2:34]

And: The stone which the builders rejected, the same is become the head of the corner; and he calleth him a stone elect, precious. — [Ps. 118:22]

And again a prophet saith concerning him: And behold, I saw one like the Son of man coming upon a cloud. — [Dan. 7:13]

Similar details are found listed in Justin’s writings. In his Dialogue with Trypho Justin writes that Mary is from the house of David (76); he further declares that Jesus has “no human generation (Trypho 32; First Apology 51); that he is not descended from human seed (Trypho, 63, 68); that Jesus was born in a cave near the village of Bethlehem (Trypho 78); that Jesus’ birth fulfilled a prophecy to take the power of Damascus and spoils of Samaria (Trypho 78); and that Jesus escaped all notice of others until he was an adult (First Apology 35).

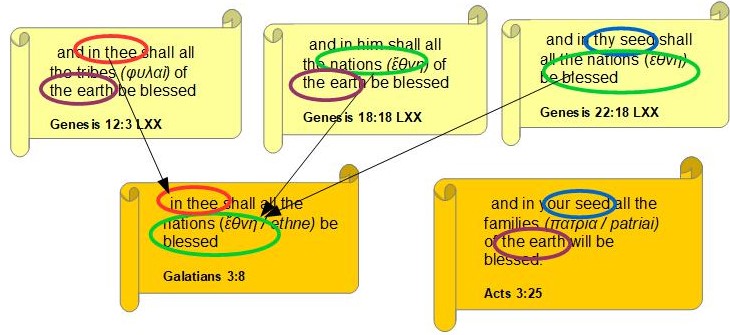

Such lists of “fulfilled prophecies” do not derive from narratives. They have all the appearance of being found independently, as some form of “testimonia”. Readers had been pondering scriptures and divining what they had to say about how the heavenly messiah was to make his appearance in the world of humankind. From this pool of testimonies, presumably crafted by prophets of some sort, different scribes took raw material to create their narratives. Each of these narratives had its own theological theme. Thus, the Infancy Gospel of James was focused on demonstrating that “history proved” the sacred and eternal virginity of Mary; the Ascension of Isaiah took those elements that it could use to demonstrate that Jesus was not contaminated by flesh even though coming as flesh or in the appearance of it; Matthew sought to represent Jesus as a second Moses who brought out of Egypt a “mixed multitude” of Israelites and gentiles; Luke, to show Jesus began his career with the Jews alone, “to the Jew first“.

Such is the viewpoint of Enrico Norelli. The above is his thesis on how we have come to have such widely diverging nativity stories of Jesus. Quite likely, but I also think that certain authors — especially “Luke” — were themselves creative enough to find scriptural “prophecies” as needed for their respective narratives.

Norelli asks about the names of Mary and Joseph after lengthy discussions about the apparent creation of the “testimonia” listed above. He can’t see those details being found in scriptural fulfilment so suspects they probably were historically grounded as the names of the real parents of Jesus.

I find that reasoning problematic: every detail is taken from “fulfilled prophecy” except the names of two parents? Other scholars have indeed found the names of Mary and Joseph in “prophecy”:

- How Joseph was piously invented to be the “father” of Jesus

- Symbolic Characters #3: Mary, Personification of the Jewish People, “Re-Virgined”

(The meaning of Mary’s name is further mentioned in The Symbolic Characters in the Gospels: Personifications of Jews and Gentiles)

Many of Enrico Norelli’s journal articles and book chapters are available on academia.edu

Norelli, Enrico. 2012. “Wie Sind Die Erzählungen Über Maria Und Josef in Mt 1-2 Und Lk 1-2 Entstanden? M. Navarro Puerto; M. Perroni (Ed.), Evangelien. Erzählungen Und Geschichte. Deutsche Ausgabe Hrsg. von I. Fischer Und A. Taschl-Erber (Die Bibel Und Die Frauen. Eine Exegetisch-Kulturgeschichtliche Enzyklopädie. Neues Testament 2,1), Stuttgart, Kohlhammer. https://www.academia.edu/4092799/Wie_sind_die_Erz%C3%A4hlungen_%C3%BCber_Maria_und_Josef_in_Mt_1-2_und_Lk_1-2_entstanden.

———. 2010. “La Letteratura Apocrifa Sul Transito Di Maria E Il Problema Delle Sue Origini Accessed June 14, 2020a. https://www.academia.edu/5261203/La_letteratura_apocrifa_sul_transito_di_Maria_e_il_problema_delle_sue_origini.

———. 2011. “Les Plus Anciennes Traditions Sur La Naissance De Jésus Et Leur Rapport Avec Les Testimonia C. Clivaz [et alii] (ed.), Infancy Gospels. Stories and Identities (WUNT), Tübingen, Mohr Siebeck. Accessed June 14, 2020b. https://www.academia.edu/37751916/Les_plus_anciennes_traditions_sur_la_naissance_de_J%C3%A9sus_et_leur_rapport_avec_les_testimonia.