This post continues an exploration into the origin of the gospel figure of Jesus, in particular the case made by Nanine Charbonnel [NC] in Jésus-Christ, Sublime Figure de Papier.

This post continues an exploration into the origin of the gospel figure of Jesus, in particular the case made by Nanine Charbonnel [NC] in Jésus-Christ, Sublime Figure de Papier.

[To readers not so interested in the depth of these posts I have added an apology at the end.]

Though Jesus and Christianity appear to most of us as being very different from what we think of as Judaism, NC is setting forth reasons to believe that Christian beliefs about Jesus (that he was God in the flesh) were in fact natural adaptations of certain Jewish beliefs in the Second Temple era and prior to what we now think of as orthodox rabbinic Judaism. The view that early Christian and Jewish beliefs were much closer to each other than we tend to imagine today is not new among scholars. NC, therefore, can quote a critical work of the life of Jesus from the early 1800s in partial support of her argument that the figure of Jesus we read about in the gospels was initially created as a personification of various attributes of God.

Personified attributes of God in certain Jewish traditions

Pre-Christian Jewish thought has long been known to have personified various attributes of God. In 1835 David Friedrich Strauss in his Life of Jesus Critically Examined wrote:

We find in the Proverbs, in Sirach, and the Book of Wisdom, the idea of a personified and even hypostasized Wisdom of God, and in the Psalms and Prophets, strongly marked personifications of the Divine word; and it is especially worthy of note, that the later Jews, in their horror of anthropomorphism in the idea of the Divine being, attributed his speech, appearance, and immediate agency, to the Word (מימרא) or the dwelling place (שכינתא) of Jehovah, as may be seen in the venerable Targum of Onkelos. These expressions, at first mere paraphrases of the name of God, soon received the mystical signification of a veritable hypostasis, of a being at once distinct from, and one with God. As most of the revelations and interpositions of God, whose organ this personified Word was considered to be, were designed in favour of the Israelitish people, it was natural for them to assign to the manifestation which was still awaited from Him, and which was to be the crowning benefit of Israel,—the manifestation, namely, of the Messiah,—a peculiar relation with the Word or Shechina. From this germ sprang the opinion that with the Messiah the Shechina would appear, and that what was ascribed to the Shechina pertained equally to the Messiah: an opinion not confined to the Rabbins, but sanctioned by the Apostle Paul.

(Strauss, Life, Pt II Ch IV §64. Bolding is NC’s re the French translation)

NC rightly remarks that many aspects of the texts of the New Testament would remain obscure without reference to the later Jewish writings. Talmudic writings, though late, certainly contain ideas, debates, sayings, that were known before the fall of the temple in 70 CE. NC goes further, however, and suggests that even the late Jewish mystical writings of the Kabbalah incorporate ideas much older than the Middle Ages. This is an area I have read too little about so all I can do at this point is repeat NC’s point and attach questions to them, especially when citing a Kabbalist.

In the nineteenth century, Joseph Salvador (in 1838), then especially the rabbi of Livorno Elijah Benamozegh (in a manuscript of 1863 which has remained unpublished, but written in French and having been sent to Paris, and which has just been published), La Kabbale et L’origine des Dogmes Chrétiens, have thrown very interesting light on these questions – if at least one accepts to name Kabbalah all that has not been accepted by rabbinical Judaism, and which must have had much more older than the Middle Ages alone. [machine translation of NC, p. 313. I have ordered a copy of La Kabbale but will have to wait a couple of weeks for it to arrive.]

NC further indicates that, according to Benamozegh, New Testament passages relating to the relationship between Father, Son, Holy Spirit under various metaphors and the incarnation of the Word of God are explained best by certain of those mystical notions, such as the Malkuth. The types of esoteric Jewish beliefs that entertained some of these ideas presumably from as early as the Second Temple era also would go a long way towards explaining the origins of various forms of Christianity (e.g. gnostic) that were delegated as heretical by what became orthodoxy. As mentioned, I know too little at this stage about Kabbalism to comment, although I have to add that the relevance of Kabbalist ideas to NC’s quest is underscored by Daniel Boyarin in Border Lines.

We are now in a position to state the result of our discussion. It has led us to the conclusion which, in view of those ideas of the value of suffering and particularly of the suffering of the righteous and of martyrs which we enumerated above, we should have expected, namely, that the assumption is at least possible that the conception of a Suffering Messiah was not unfamiliar to pre-Christian Judaism. (p. 283)

So returning to Boyarin (with NC), some of whose more fascinating ideas cohere with other works by his scholarly peers*, NC directs us to this section of Border Lines:

This leads me to infer that Christianity and Judaism distinguished themselves in antiquity not via the doctrine of God, and not even via the question of worshiping a second God (although the Jewish heresiologists would make it so, as we shall see in the next chapter), but only in the specifics of the doctrine of this incarnation.78 Not even the appearance of the Logos as human, I would suggest, but rather the ascription of actual physical death and resurrection to the Logos was the point at which non-Christian Jews would have begun to part company theologically with those Christians—not all, of course—who held such doctrines.

78. It is not beside the point to note that, in traditional Jewish prayer from the Byzantine period to now, prayer to the “attributes” of God is known as well as prayer to the Ministering Angels (Yehuda Liebes, “The Angels of the Shofar and the Yeshua Sar-Hapanim,” Jerusalem Studies in Jewish Thought 6, no. 1-2 [1987]: 171-95, in Hebrew). These prayers were rectified by nineteenth-century Jewish authorities, who saw in them (suddenly?) a threat to monotheism.

[NC quoted the bolded part in the French translation. The passage above is from Boyarin, Border Lines, pp 125 and 294]

In the next section of this post, we will delve further into Boyarin’s discussion on the relationship between early Christianity and Judaism.

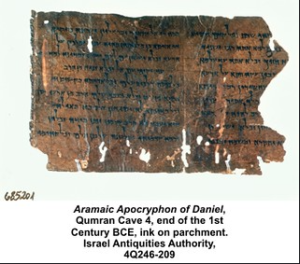

Innovative interpretations: theology of the Memra in the Targum

The Word: Logos (Greek); Memra (Aramaic) Continue reading “Jewish Origin of the “Word Became Flesh” / 2 … (Charbonnel: Jésus-Christ, Sublime Figure de Papier)”