— Russell Gmirkin, Plato and the Creation of the Hebrew Bible, p. 238

I took the bait and the following post is an outcome: Weinfeld’s points of comparison between the biblical narrative and the Aeneid. Weinfeld’s proposed explanations for the similarities follow.

But first, a note for those who would dismiss the relevance of any such comparison on the basis that Virgil’s famous epic clearly postdates the biblical narrative and is far from likely influenced by anything in the Pentateuch:

It should be clear, first of all, that the Aeneas legend and the stories associated with it are quite ancient and may be traced back — as the various paintings on archaeological artifacts show — to the seventh century B.C.E. That these stories actually belong to the genre of “foundation stories” about foundations of cities by single heroes has been noted by F. B. Schmid, who surveyed the foundation legend of the Greeks, and observed that the Aeneid epic was patterned after them.[39] (Weinfeld 1993, pp. 16f)

|

A Man Leaving a Great Civilization and Charged with a Universal Mission |

|

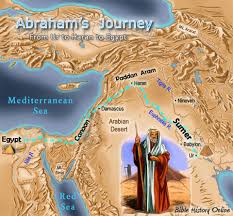

| Aeneas leaves the famous city of Troy | Abraham leaves the great civilization of Mesopotamia, Ur of the Chaldaeans |

| with his wife, father and son — Creusa, Anchises and Ascanius | with his wife and father — Sarah and Terah |

| in order to establish a new nation | in order to establish a new nation |

| Virgil calls Aeneas “Pater” (2:2) | Abraham was known as the father of the nation |

| Aeneas delays in Carthage | Abraham delays in Aram |

| which later becomes Rome’s great enemy | which later becomes Israel’s enemy |

| “An important theme in the Aeneid is the tension between Rome and Carthage. There is a danger that Aeneas will marry Dido, the queen of Carthage, and thus that the message of Latium could fail; the gods of Aeneas, therefore, work to bring the hero back on track toward Rome.

“Mercury, the messenger of the gods, is sent by Jupiter to warn Aeneas not to forget the promise that his mother, Venus, had held out for him, and to urge him to sail at once to his destined land (4:219–37). “After Aeneas’s delay, Mercury is sent to him again, this time in a dream, and warns him once more to leave Carthage (4:554–70).” |

“A similar situation may be discerned in the Jacob stories. There is the danger that Jacob will stay in Aram Naharaim, where he journeyed to flee from his brother Esau and to marry Laban’s daughters. Had he stayed, he would have abandoned his mission to the promised land.

“Therefore, Jacob is called to return to his native land, and the call is made, as in the Aeneid, twice: the first time through direct revelation (v. 4) “and the second time through revelation by dream (v. 11).” |

| “Although in the final stage of Genesis (ch. 31) Jacob is said to leave Aram because of his quarrel with Laban, an older stratum (Elohistic?) in the chapter (vv. 10, 12a, 13) creates the impression that the affluence of Jacob (vv. 10, 12a; cf. 30:43) might have caused him to stay in Aram, necessitating the divine call to return to Canaan.” | |

| Finally, his son Ascanius reaches Lavinium, and later his son gets to Alba-Longa. His descendants reach Rome, which is destined to rule the world. | He reaches Canaan, the Land of promise, out of which his descendants will rule other peoples. |

| Weinfeld points out that the traditions of Aeneas were applied during the time of Augustus to the Roman Empire so that Aeneas became not only the father of Rome itself but also a prefiguration of the ruler of the entire world. The prophecy of Poseidon in the Iliad 20:307 that Aeneas will rule over the Trojans, (cf. Homeric Hymns, AD Venerem 3:196–97), is indeed recorded (reinterpreted) in an oracle in Aen. 3:97–98 saying that the house of Aeneas shall rule “over all lands”: hic domus Aeneae cunctis dominabitur oris. | Weinfeld believed the story of Abraham originated during the time of King David and served to justify Israel’s aspirations to “rule … an empire, stretching from the Euphrates to the River of Egypt (Gen. 15:18).”

(I would add that Paul interpreted the promises given to Abraham as indicating that the entire world would belong to his heirs.) |

| “In both cases we have examples of an ethnic tradition later developed into an imperial ideology;

“in both, we are presented with a divine promise given to the father of a nation who later becomes a messenger for a world mission.” |

|

|

Gap between Migration of the Ancestor and the Actual Foundation |

|

| Jupiter tells Aeneas (1:270f.) that 333 years will pass before the birth of the twins — that is, before the foundation of Rome. | God tells Abraham that 400 (or 430) years will pass before his descendants will inherit the promised land (Gen. 15:13; cf. Exod. 12:41). |

| Weinfeld treats the older Romulus story as basically a Latin account, while the Aeneas version has its source in the writings of the Greek poets; during the course of the third century, the Aeneas and Romulus legends began to be combined, and to fill the gap after the supposed landing of Aeneas, a long Trojan dynasty was invoked. | According to Weinfeld, a similar situation is encountered in ancient Israel: the birth of the nation is traditionally set in the Exodus and the conquest of Canaan, but the remote ancestor of Israel was sought in Ur and in Aram Naharaim. |

| The Romans adopted the Trojan Aeneas legend from the Greeks, as has been demonstrated by the artifacts from Etruria and by the adoption of the Trojan Penates | “The Genesis traditions about the nomadic ancestors of Israel in the Syro-Palestinian area, as well as the traditions about their El-worship in Canaan, seem to have been adopted from peoples who lived in the region before the settlement of the Israelite tribes. . . . The Pentateuchal traditions themselves attest that the Patriarchs did not know Yahweh, the name of the national God of Israel (Exod. 6:3 f., cf. Exod. 3:13–15).

“The very name Jacob may prove the local nature of the patriarchal traditions. R. Weill has hypothesized that the Israelites received the stories about Jacob — a name known to us as a prince of the Hyksos dynasty, Yaqob-hr — from the Canaanites. This theory has recently been confirmed by A. Kempinski on the basis of an investigation of the scarab found in Shiqmonah, inscribed with the name Yaqob-hr. Thus, it appears that the Israelites received from the Canaanites the legends about Jacob who went down to Egypt with the Hyksos.” |

|

Promise at Stake |

|

| When Aeneas was endangered by the sea storms Venus intervened on his behalf and prayed to Jupiter: “O you . . . who [rule] the world of men and gods, what crime . . . could my Aeneas have done. . . . Surely it was your promise . . . that from them the Romans were to rise . . . rulers to hold the sea and all lands beneath their sway, what thought . . . has turned you?” (1:229 f). | When Jacob is endangered by the threat of Esau’s advancing army, he prays: “Save me from my brother Esau; else I fear he may come and strike me down . . . yet, you have said . . . I will make your offspring as the sand of the sea” (Gen. 32:12–13). |

| “The promise is seen, then, in Israel, as well as in the Roman epic, as something that could not be taken back: a divine commitment not to be violated (cf. Exod. 32:11–14). Connected with the promise at stake are the omens that point to certain difficulties in the realization of the divine promise.” | |

| When “Aeneas and his men sit at the table with Jupiter, the Harpies (raptors) fall upon the table and with their unclean touch contaminate the dish. Aeneas’s comrades drive them away with their swords (3:22 f.). The onslaught of the Harpies was considered a bad omen, and indeed, after this event the seer Celaens predicts that before Aeneas will finish building the promised city, famine will overtake him and his men.” | “A similar phenomenon is encountered in Gen. 15: when Abraham is cutting the pieces of the sacrificial animals of the Covenant, birds of prey come down upon the carcasses, and Abraham drives them away. Immediately afterward, he is informed that his descendants will be enslaved and oppressed in Egypt before they will reach the promised land (Gen. 15:13).” |

| The Pious Ancestor | |

| “As Galinsky has suggested, the image of pious Aeneas is a back projection from pious Augustus.” | Abraham is described as God-fearing (yr’ ‘lhym[*] , Gen. 22:12), “walking before the Lord” (24:40), and “listening to his voice” (22:8; 26:5; cf. 17:1), much like David, who is depicted as “walking before God with righteousness and perfection” (1 Kings 3:6; 9:4; 14:8; 15:3; cf. Ps. 132:1; 2 Chron 6:42). It was these moral-religious qualities that made Abraham and David worthy of God’s promise for land and kingdom, respectively. Both promises—and only these promises—are defned as hbrytwhhsd[*] “the covenant of grace.” Furthermore, in connection with the promise of descendants we also fnd identical phraseology not attested elsewhere: “One of your own issue,” ‘sr ys’ mm’yk[*] , in 2 Sam. 7:12 and Gen. 15:4.[22] The considerable overlap between the two fgures has been noted, and, as I have suggested elsewhere, Abraham the warrior in Gen. 14 behaves quite similarly to David the warrior in 1 Sam. 30.[23] The suggestion that Abraham is a retrojection of David seems quite plausible, therefore. |

| Like the Abraham-David imagery in Israel, the Aeneas-Augustus imagery in Rome reflects a later stage of the crystallization of the story. As is well known, the Abraham cycle in Genesis represents a later stage than the Jacob cycle, which appears to be closer to the original tradition and less fragmentary than the Abrahamic stories.[25] The Jacob stories contain motifs that are even closer to the foundation traditions of the Greek-Roman world. | |

|

The Ancestral Gods transferred to the newly founded site |

|

| In the journey of Aeneas to Latium the household gods (who act as guardians) play an important role. They appear in the accounts of Hellanicus (fifth century B.C.E. ) and Timaeus (third century B.C.E. ), and Virgil indicates that bringing the gods to Italy is the purpose of Aeneas’s journey (1:6): “Till he should build a city and bring his gods to Latium” (1:5–6).

On an Etruscan amphora of the fifth century B.C.E. next to Aeneas is the figure of his wife, Creusa, carrying a cushion with stripes, which apparently contained these sacred household gods. |

Rachel, Jacob’s wife, takes with her the household gods in order to bring them to the new land (Gen. 31:19, 34). Josephus adds that it was the custom to take along these objects of worship when going abroad (Ant. 18:344).

That household gods were kept in something similar to a cushion may be deduced from the fact that Rachel hid them in the cushion of a camel (Gen. 31:34): the cushion of the teraphim could be mistaken for the riding cushion of the camel. |

| “Furthermore, according to Plutarch (Camillus 20:6 f.), the sacra of Troy were stolen by Aeneas, much as the teraphim were stolen by Rachel (Gen. 31:19, 34), another parallel that brings the analogy even closer. The Danites, too, on their way to the new territory in the north, steal the teraphim from Micah’s house (Judg. 18:4 f.).[30] The theft of the sacra from Troy is prevalent in the various traditions about Aeneas (cf., e.g., Dionys. Hal. 1:69:3), which may explain the importance of the thefts of the teraphim by Rachel, on her way to the new land, and by the Danites, when they were leaving to settle their new territory.” | |

| In the Aeneas tradition, we find that six hundred men took care of the gods in Lavinium (Dionys. Hal. 1:67:2). | In Judg. 18:16 we find that six hundred Danites guarded the men who took the teraphim. |

|

The Burial Place of the Founder |

|

| The tomb of the hero played a very important role in the Greek world; a tomb of Aeneas, is mentioned by Dionysius of Halicarnassus (1:64:3) as existing in his own days in Lavinium. | According to the Jacobic cycle, Shechem was the foundation city where the ancestral gods were hidden and was also the location of Jacob’s and Joseph’s tombs (Gen. 50:5; cf. 33:19; Josh. 24:32). |

| “Furthermore, as in Israel, where we find a rivalry between Shechem and Hebron concerning the tomb of Jacob, in Rome we are told by Dionysius of Halicarnassus that “though one place received the body of Aeneas, the tombs were many . . .; he was honored with shrines in many places” (1:54:1). This emphasis on the place of burial explains the importance attached to the tombs of the Patriarchs in Shechem (Gen. 33:19; cf. Josh. 24:32) and in Hebron (Gen. 23).” | |

| “The transfer of the bones of the hero from a foreign country, which is attested in connection with Jacob and Joseph (Gen. 47:30; 50:25; cf. Exod. 14:19; Josh. 24:32), was also an important matter with the Greek founders. As the bones of Joseph, the ancestor of Joshua, were brought from Egypt to Shechem, we read in Plutarch that the bones of Theseus, the national hero of Athens, were brought from the island of Skyros to Athens (Plutarch:Theseus 36). Similarly, we learn in Herodotus that the bones of Orestes, the son of Agamemnon, were sought by the Spartans and brought to Sparta (1:67–68).” | |

How do we explain these common features in two works of literature created hundreds of years apart and reflecting two entirely different cultures?

Weinfeld’s book was published in 1993. Since then the “minimalist-maximalist” debate has raged among scholars of the Old Testament — that is, between those who rely primarily upon the archaeological evidence and interpret the biblical literature through such “primary evidence” for the reconstruction of history and those who rely upon the biblical texts as their guides to interpreting the archaeological remains. (See my outline of P.R. Davies’ book that has been said to have propelled this debate into wider scholarly and public awareness.)

Weinfeld interpreted the similarities through similar political situations: comparing, for example, the newfound prominence of the kingdom of David with the new order initiated by Augustus. He also adhered closely to the documentary hypothesis as it explained the development of the biblical narratives and accordingly interpreted various contradictions within these traditions as evidence of attempts to combine into a single narrative both various local and foreign traditions. Similarly, he saw contradictions within the Latin mythical narratives as evidence of past rival traditions.

I suspect since Weinfeld’s time there may be some scholars who would prefer to see the biblical narrative as cut from the cloth of foundation narratives originating from the time of the classical and Hellenistic Greeks. That certainly appears to be Gmirkin’s thesis.

Weinfeld, Moshe. The Promise of the Land: The Inheritance of the Land of Canaan by the Israelites. Berkeley: University of California Press, 1993.

Neil Godfrey

Latest posts by Neil Godfrey (see all)

- What Others have Written About Galatians (and Christian Origins) – Rudolf Steck - 2024-07-24 09:24:46 GMT+0000

- What Others have Written About Galatians – Alfred Loisy - 2024-07-17 22:13:19 GMT+0000

- What Others have Written About Galatians – Pierson and Naber - 2024-07-09 05:08:40 GMT+0000

If you enjoyed this post, please consider donating to Vridar. Thanks!

Very impressive systematic comparison!

Thanks, Neil. A lot of work! But personally I must confess I fear the list of important differences would be longer. With the legend of Aeneas Rome gave itself a very old, divine and royal ancestor, the typical hero of all Greek epic poems. Abraham was a shepherd, an impossible hero in ancient Greek literature. Friendly greetings

I do not recall if I clarified in the post that Weinfeld does not suggest a borrowing of the Greek myth by the biblical authors: rather, he believes the best explanation was that both epic tales originated in a common literary genre of some sort.

Though of course some “minimalist” arguments since then, and Gmirkin’s work in particular, would argue for a direct Greek influence on the biblical writings.

I’m sorry if my personal doubts about the comparision seems to disrespect your post. That was not my intention. My own impression is that in some early Jewish writings are very unique themes, patterns und styles which cannot traced back to Greek literature. It may be that I’m simply more interested in the differences than the similarities.

Please don’t apologize. You expressed a common criticism of this sort of discussion and I’m glad you raised it since it gave me an opportunity to reply with my own thoughts to the contrary. All is good. I appreciate the exchange.

Thanks. I think that one of the decisive significant differences between Genesis and Greek epic poems is indeed style.

One of the scholars who noted this was Erich Auerbach. In his well-known „Mimesis: The Representation of Reality in Western Literature“ he wrote: „We have compared these two texts, and, with them, the two kinds of style they embody, in order to reach a starting point for an investigation into the literary representation of reality in European culture. The two styles, in their opposition, represent basic types: on the one hand (Homer [my note]) fully externalized description, uniform illumination, uninterrupted connection, free expression, all events in the foreground, displaying unmistakable meanings, few elements of historical development and of psychological perspective; on the other hand (Genesis), certain parts brought into high relief, others left obscure, abruptness, suggestive influence of the unexpressed, “background” quality, multiplicity of meanings and the need for interpretation, universal-historical claims, development of the concept of the historically becoming, and pre occupation with the problematic.“

Even after 50 years his “Odysseus’ Scar” seems intriguing to me.

http://www.westmont.edu/~fisk/Articles/OdysseusScar.html

It’s an interesting question and I should revise my Auerbach, too. What about the stories of Joseph and then of David and Saul, though? Do you think A’s style criticism works with those two narratives?

I have read a few works comparing Herodotus’s Histories with Primary History and one difference pointed out is the absence in the Hebrew texts of a personal narrator. The narrator’s voice comes through directly and personally in much of the Greek literature, but is strikingly absent in most of the Hebrew works. If that is the real difference of significance — the narrative voice and intrusive commentary — then I wonder if we might be looking at Greek/Hellenistic literary influence but adapted to the impersonal narrative style of the Near Eastern literature.

But I have much more to learn about all of this.

Difficult question. I would say not in the same way. I think that stories as “the call of Elisha” or “David at Nob” may be not far away from this “mysterious” Genesis style. In contrast, the style of Hannah’s song should have a few parallels in Greek literature.

Indeed, differences are absolutely necessary or logically there could be nothing to compare to begin with — we would only have the same narrative written multiple times. Differences are indeed as important as similarities for our interpretations and explanations. The differences between the Aeneid and Homer’s epics are surely more numerous than the similarities and those differences are what enable us to understand the similarities and the way and reasons Virgil has interpreted and adapted Homer. (e.g. One book instead of two; Aeneas sails trouble-free around an area where Odysseus met catastrophe from Scylla and Charybdis…)

See How Literary Imitation Works: Are Differences More Important than Similarities?

On Parallels

When is a parallel a “real parallel”?

Sandmel’s discussion on “parallelomania” is a must read, as are the various works on literary criteria.

(You may not be aware that Near Eastern kings called themselves “shepherds”; and that Abraham had the reputation of being a prominent astrologer; and that the first we learn of Abraham’s socio-economic status in Genesis itself (12:16) he is said to be the ruler of a vast household that made an income from a range of livestock and attracted the attention of kings and princes wherever he went, also in direct firstborn line from Noah — not a nobody.)

I often wonder why no one is baffled by the fact that the Chaldeans lived in Ur in a time contemporary with the Babylonians rather than the Sumerians.

Commentators and historians do indeed raise this anomaly. On its own it may not always be considered decisive, however, since it is the sort of detail that one can imagine a copyist or later editor at some time adding to an otherwise earlier tale.

It isn’t so much what they might have added but what’s missing that’s baffling to me. The way I read it, this was originally written in a time contemporary with the Chaldeans so the use of the name isn’t out of place, but even at that time many things that were known about Sumer aren’t attested in Genesis.

This is the opposite to the fact that Aeneus wasn’t fully attested until Roman tradition. The Romans built out their own tradition from threads of previous traditions, but the Hebrews either ignored or tore down previous traditions.

People do this in modern times because of inconvenient facts. In the Christianity I came from, I look back on it now as if Christians were begging for biblical tradition to originate from oral tradition in spite of the fact that writing was used since before the time of the “flood”.

If you make up something original that isn’t contradictory to other stories you don’t run into this sort of trouble.

thnxs Neil,

a comparison is interesting if nothing else…here it raises questions. And some readers do not seem to realise you concerned yourself with foundation myths rather than :”copying”

Certainly interesting and thought provoking to list these parallels. Would like to make a few small remarks, since Gmirkin’s theories have been discussed in general elsewhere (perhaps you will get to discuss these reviews too?):

– I don’t think there is/was any “F. B. Schmid” who wrote about foundation myths. I suppose P.B. Schmid was meant. But even so, this remains a rather obscure reference for such an important starting point for Weinfeld’s (and subsequently Gmirkin’s) theories.

– To dismiss that “Virgil’s famous epic clearly postdates the biblical narrative and is far from likely influenced by anything in the Pentateuch” it is not sufficient to show that myths around Aeneas existed since the 7th Century BCE: the ancient Greek Aeneas stories were different from the Roman stories. Aeneas was an enemy of the Greeks, and only a minor character in the Iliad. The Romans modeled themselves on a true ‘Trojan’ hero to support their perception of superiority over the Greek culture.

– In these discussions, the impression is given that the Greek ‘foundation myths’ were produced by the Greeks in perfect isolation. But isn’t it more likely that the Greeks interacted with other cultures, e.g. in Mesopotamia? It is known that Greeks had contacts with Babylon, and – of course – Persia. And the Israelites did that too. Can we exclude that the parallels in the Greek and Israelite stories originate in common Mesopotamian sources?

For discussion of Roman-Israelite literary interaction, see e.g.

– Nicholas Horsfall, Vergilius (1959-) Vol. 58 (2012), pp. 67-80

– Jan N. Bremmer, Vergilius (1959-) Vol. 59 (2013), pp. 157-164

Do you have a source for “P.B. Schmid”? “F.B.” is consistently used throughout Weinfeld’s references, though of course mistakes are made by authors and machines: (even in Russell Gmirkin’s book E.N. Tigerstadt regularly appears instead of the correct E.N. Tigerstedt, with an e, not an a). In the Library of Congress name authorities and on the university’s citation page I can only see Benno Schmid.

As for citing an unpublished thesis, such references are not uncommon in scholarly works. But the evidence supplied for the existence of the Aeneas story going back to the seventh century BCE was “various paintings on archaeological artefacts”. If I had access to Schmid’s thesis and could translate it I would offer more, but I am sure there must be other references extant pointing to the evidence of the paintings on (presumably) pottery. I’d be interested in seeing the details.

The comparison is by no means central to Gmirkin’s thesis, by the way. In fact he mentions the Aeneid only once in the body of his text and in doing so comments on its exceptional nature in comparison with related Greek stories, and twice more in endnotes, both times in passing.

I hope a post I have since published as a postscript addresses another query you and another commenter raised.

Thanks. I found references to P.B. Schmid here:

http://katalog.ub.uni-heidelberg.de/cgi-bin/titel.cgi?katkey=65870105

https://books.google.nl/books/about/Studien_zu_griechischen_Ktisissagen.html?id=KWxRmgEACAAJ&redir_esc=y

https://www.researchgate.net/publication/33859301_Studien_zu_griechischen_Ktisissagen

No e-books found, unfortunately.

Regarding the paintings of Aeneas, Weinfeld may be citing William S. Anderson’s ‘The Art of the Aeneid’. I think that these paintings mostly depict scenes from the Illiad.

I have requested a copy of the electronic thesis. Maybe either the P or the F refers to a title. Will try to find out.

Anderson’s book is about the literary art, not the pottery art.