Chapter 13

Chapter 13

The Quest for History: Rule One

.

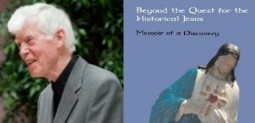

The theme of chapter 13 in Thomas Brodie’s Beyond the Quest for the Historical Jesus: Memoir of a Discover syncs well with a recurring theme on this blog. I have posted on it repeatedly and alluded to it constantly. I even posted on the contents of this chapter 13 soon after I began reading Brodie’s book and before I considered doing this series. That earlier post was Quest for History: Rule One — from Brodie’s Beyond the Quest for the Historical Jesus.

Many scholars of Christian origins (biblical and religion scholars, theologians) write in the belief that the most important thing to grasp about the narratives and sayings in the Gospels is the historical context that gave rise to them.

And yet, and yet, and yet. Being first in importance does not necessarily mean being first in the order of investigation. The first thing to be sorted out about a document is not its history or theology — not the truth of background events or its ultimate meaning — but simply its basic nature.

For instance, before discussing a will — its possible many references to past events, and its provisions for distributing a legacy — the first thing to be established is whether it is genuine, whether it is a real will. (p. 121, my bolding)

Its basic nature! The nature of the text we are reading! Exactly. One theologian who regularly refers to himself as a historian has insisted that historical analysis of the Gospels has nothing to do with literary analysis and that literary analysis has no relevance for historical analysis. That is flat wrong. Even at a very superficial level everyone necessarily does some form of literary analysis in order to determine how to interpret the content of what they are reading. Is what we are reading a diary, a parody, an advertisement, an official news report, a novel? Deciding that question involves some basic level of literary analysis.

The commonly expressed view that the Gospels are a form of ancient biography actually arises more from the a priori assumption that they contain or are based ultimately on biographical data than a theoretical analysis of the genre. For an analysis of the influential work of Burridge (whose work arguing for the Gospels being a form of biography is widely taken for granted but less widely analysed critically) see other Vridar posts in the Burridge archive. For discussions of a work that is, by contrast, a theoretically grounded analysis of the genre of the Gospel of Mark see the Vines archive.

(Unfortunately not even classical studies helps much here since, I’ve been informed, questions of genre generally remain fairly fluid in that department. But biblical studies does elicit certain distinctive questions critical for cultural reasons so genre analysis of biblical literature does deserve to be taken more seriously.)

But enough of my take. This series is meant to be about Brodie’s views. So for the sake of completeness I have decided to copy my earlier post within this series here. If you’ve already read it then think of this as a refresher. It’s a topic that can’t be overstated given that it appears to be utterly lost on the bulk of the present generation of scholars of Christian origins. Continue reading “Making of a Mythicist, Act 4, Scene 2 (“What Is Rule One?”)”