All posts in this survey of Nanine Charbonnel’s book are archived at Charbonnel: Jesus Christ sublime figure de papier.

All posts in this survey of Nanine Charbonnel’s book are archived at Charbonnel: Jesus Christ sublime figure de papier.

Getting Real

The striking difference between pre-Christian Jewish concepts and those of Christianity is that the latter eschewed abstract notions of messiahs and divine messengers and fleshed them out with names and personalities. Where we read in the Qumran scrolls about a “Teacher of Righteousness”, Priests, Messiahs, Overseers, in the early Christian literature we meet personal names (Jesus, John) and titles (Christ, Baptist) and even signatures (Paul et al.) The new ideas were conveyed as stories, not merely abstract doctrines. Charbonnel cites André Paul, page 84, Qumrân et les Esséniens : l’éclatement d’un dogme:

We were no longer in the theoretical but in the real. We are talking about concrete people, who, moreover, have names. (Original: On n’était plus dans le théorique mais dans le réel. Il s’agit de personnes concrètes, qui de surcroît ont des noms.)

The question is: Were these the names of real people or were they the names of personifications of things to do with God and Israel and that pertain to salvation. Does the name of Jesus enter our history because it was the name of a historical figure or was it born as a personification of the Name of God? In the earlier posts, we saw how Jesus was made the personification of the People of God and of Yahweh on earth, and of the Temple and Glory of the Divine Presence (Shekinah).

Veneration of the Name

Within the heart of the Judaism of the Second Temple was the veneration of the name of God.

The name Jesus, as we know, derives from the Hebrew meaning “It is Yahweh who saves”.

The Jesus of the New Testament, Charbonnel posits, is developed in part from the two other greats named Jesus in the Old Testament.

Jesus I

First, we have Joshua (= Jesus) who led Israel into the Promised Land. Today few of us would connect God’s instruction to Moses about his messenger (commonly translated “angel”) bearing the divine name with Joshua, but we know from the second century Justin that early Christians did make that connection.

Exodus 23:20-21

See, I am sending an angel [= messenger] ahead of you to guard you along the way and to bring you to the place I have prepared. Pay attention to him and listen to what he says. Do not rebel against him; he will not forgive your rebellion, since my Name is in him.

Here is Justin’s understanding taken from his Dialogue with Trypho, 75:

Moreover, in the book of Exodus we have also perceived that the name of God Himself which, He says, was not revealed to Abraham or to Jacob, was Jesus, and was declared mysteriously through Moses. Thus it is written: ‘And the Lord spake to Moses, Say to this people, Behold, I send My angel before thy face, to keep thee in the way, to bring thee into the land which I have prepared for thee. Give heed to Him, and obey Him; do not disobey Him. For He will not draw back from you; for My name is in Him.‘ Now understand that He who led your fathers into the land is called by this name Jesus, and first called Auses(Oshea). For if you shall understand this, you shall likewise perceive that the name of Him who said to Moses, ‘for My name is in Him,’ was Jesus. For, indeed, He was also called Israel, and Jacob’s name was changed to this also.

Justin is writing in the second century but his explanation of the choice of the name Jesus does have a “midrashic” rationale.

Jesus II

Then there is another Jesus or Joshua, the high priest who, on his return with his people from the Babylonian exile led them in the reconstruction of the temple.

Zechariah 6:9-11

Zechariah 3:1 Then he showed me Joshua the high priest standing before the angel of the Lord, and Satan standing at his right side to accuse him.The word of the Lord came to me: “Take silver and gold from the exiles Heldai, Tobijah and Jedaiah, who have arrived from Babylon. Go the same day to the house of Josiah son of Zephaniah. Take the silver and gold and make a crown, and set it on the head of the high priest, Joshua son of Jozadak. Tell him this is what the Lord Almighty says: ‘Here is the man whose name is the Branch, and he will branch out from his place and build the temple of the Lord. It is he who will build the temple of the Lord, and he will be clothed with majesty and will sit and rule on his throne. And he will be a priest on his throne. And there will be harmony between the two [roles – Priest and King].’”

Jesus III

The third Joshua/Jesus inherits the roles of the first two.

Acts 2:21

And everyone who calls on the name of the Lord will be saved.

Romans 10:13

For everyone who calls on the name of the Lord will be saved.

Both are quoting Joel.

Joel 2:32

And everyone who calls on the name of the Lord will be saved.

To paraphrase Charbonnel, the essence of Christianity is the affirmation that the Lord, the Name of the Lord, and Jesus Christ, are one. In Joel, the call was to invoke the name of the God of the Covenant. This invocation now passes to Jesus because Jesus himself is recognized as the one with the name of God.

The narrative of the Gospel of Luke begins with the name given to the messiah. He was (literally) “called the name” Jesus (Luke 2:21– interlinear). We find the same “called the name” formula for the Davidic Messiah in the Qumran scrolls:

4Q381, fr 15

And I, Your anointed one [=messiah], have come to understand . . . will tell others about You, for You have given me knowledge, and indeed You have endowed me with great insight . . . for I am called by Your name, my God, and for your deliverance . . . . [7-9. Wise, Abegg, Cook]

In 1 Enoch we read that the Name had a pre-existence:

1 Enoch 48:3, 6

Even before the sun and the constellations were created, before the stars of heaven were made, his name was named before the Lord of Spirits. . . . He was chosen and hidden before him before the world was created, and for ever [or, until the coming of the Age].

Paul writes from deep within this cult of the name. See 1 Corinthians 1:2 and in particular,

Philippians 2:9-11

Therefore God exalted him to the highest place and gave him the name that is above every name, that at the name of Jesus every knee should bow, in heaven and on earth and under the earth, and every tongue acknowledge that Jesus Christ is Lord, to the glory of God the Father.

Jesus, we recall, was also the personification of the Temple, and also identified with its cornerstone. We find the Name of God at the heart of the Temple and its cornerstone in a later Jewish text that is widely interpreted as an attack on Christianity, the Toledot Yeshu. I quote the relevant passage of the Toledot from Frank Zindler’s The Jesus the Jews Never Knew:

The Robbing of the Shem (the Shem = the Name, the ineffable name of God)

. . . And there was in the sanctuary a foundation-stone — and this is its interpretation: God founded it and this is the stone on which Jacob poured oil — and on it were written the letters of the Shem, and whosoever learned it, could do whatsoever he would. But as the wise feared that the disciples of lsrael might learn them and therewith destroy the world, they took measures that no one should do so.

Brazen dogs were bound to two iron pillars at the entrance of the place of burnt offerings, and whosoever entered in and learned these letters — as soon as he went forth again, the dogs bayed at him; if he then looked at them, the letters vanished from his memory.

This Jeschu [Jesus] came, learned them, wrote them on parchment, cut into his hip and laid the parchment with the letters therein — so that the cutting of his flesh did not hurt him — then he restored the skin to its place. When he went forth the brazen dogs bayed at him, and the letters vanished from his memory. He went home, cut open his flesh with his knife, took out the writing, learned the letters, went and gathered together three hundred and ten of the young men of Israel. (pp. 428ff)

Here, in an accusation against Christianity, we see Jesus literally “embodying” the perfect Name, although he does so illegitimately. Celsus records a Jew saying something similar — that the name of Jesus had magical power although it was at the behest of demons.

Origen, Contra Celsus, I.6

After this, through the influence of some motive which is unknown to me, Celsus asserts that it is by the names of certain demons, and by the use of incantations, that the Christians appear to be possessed of [miraculous] power; hinting, I suppose, at the practices of those who expel evil spirits by incantations. And here he manifestly appears to malign the gospel. For it is not by incantations that Christians seem to prevail [over evil spirits], but by the name of Jesus, accompanied by the announcement of the narratives which relate to Him ; for the repetition of these has frequently been the means of driving demons out of men, especially when those who repeated them did so in a sound and genuinely believing spirit. Such power, indeed, does the name of Jesus possess over evil spirits, that there have been instances where it was effectual, when it was pronounced even by bad men, which Jesus Himself taught [would be the case], when He said: “Many shall say to me in that day, In Thy name we have cast out devils, and done many wonderful works.”

This veneration of the name of Jesus continued throughout the subsequent centuries as witnessed in the lives of saints and the Christian Kabbalists. (See also the history of the name YHSWH – making the divine name pronounceable as Jesus — and the Sator square). Much has been written about the mystic analyses and plays with the divine name YHWH in later times but the point here is that a few of these ideas can be traced back to late antiquity and it is not unreasonable to think that their origins began in at least the gnostic forms of earliest Christianity and early elements of the Jewish religion. I may post some more details about these arcane ideas in a later post or two.

Till then, it is worth noticing that Moses created the name “Joshua” by changing the name of Hoshea to Joshua by placing at its beginning the first letter of the Tetragrammaton, God’s name. (Recall that in the earlier posts of this series that early Jewish scribes (and not only Jewish ones) found mystical significance in letters, their numerical values, puns, and so forth.) It was with the placing of this part of God’s name to Hoshea that the name Joshua was created by Moses to name the man who was to be imbued with the power of God to lead Israel into the Promised Land.

Jesus means “Yahweh saves” but such a form is not unique: the first of the minor prophets, Hosea, means “Yah saves”; Isaiah means “God saves”. We can find other instances, including Jesse and Josiah. Even Judas, from the Judah who sold Joseph, is set against Jesus by the addition of a letter at the end of the letters making up the Tetragrammaton.

The Incarnation as the Descent of the Name of YHWH

To worship YHWH was to worship his Name. The Temple was the dwelling place of his Name – 1 Kings 8:16; Deuteronomy 12:11. YHWH is even called the Name. The leading Jewish prayer, the Kaddish, is a praise of the Name of God: “Hallowed be thy Name”. The name of Jesus is: It is YHWH who saves — the lead figure in the narrative is the one who saves.

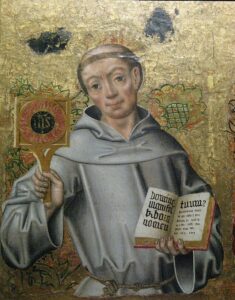

The High Priest’s function is to manifest the Name that Saves

Hence Malachi 1:11

My name will be great among the nations, from where the sun rises to where it sets. In every place incense and pure offerings will be brought to me, because my name will be great among the nations, says the Lord Almighty.

On the Day of Atonement/Yom Kippur, the day of the Great Pardon, the high priest was said to pronounce the otherwise forbidden name of YHWH in order to remove all sins from Israel. Jesus himself is modelled on the high priest — as we also read in the Epistle to the Hebrews. Citing Christian Amphoux’s La Vie de Jesus, dialogue avec Renan, Charbonnel points out that it was through Joseph that Jesus was descended from David and thus a rightful king who had the potential to replace Herod’s dynasty, while through his mother Mary Jesus was related to John the Baptist, the son of a priest. Hence Jesus had the heritage to become both a political and religious leader. As a future king, he could be seen as a threat to Rome; but if he could also be a high priest then he posed a danger to Herod and his high priest. Machine-translating Amphoux,

Simon, leader from 71 to c 110

Jude, driven from Jerusalem in 135

The dynastic lineage of John and Jesus was well constituted: the brothers of Jesus (Mt 13:55 / Mk 6:3) bear the names of the leaders of the Jerusalem community: James, from the 40s to his death, around 63; Simon, James’ cousin, from 71 to his death around 110; and Jude, driven out of Jerusalem in 135 with the other Jews. “‘

Continuing with Amphoux, at the baptism of Jesus the portrayal of the descent of the dove involves another wordplay if there is a Hebrew source behind it. Again a machine translation:

The image of ‘the descent of the dove’ is a play on the two proper nouns of the narrative: to descend is said in Hebrew y-r-d, and the name of the Jordan comes from this verb; and the dove is y-w-n-h, which gives the name of Jonah, which is an anagram in Greek of the name John (Iôna- / Iôan-). Thus, the two proper names in the story carry a message that is taken up in the image of the dove that descends. But what does this message say? John and Jonah refer to a third name, Onias, which designates the legitimate high priest, deposed in 175 B.C.; and the descent expresses the movement from heaven to earth, by which Jesus is invested with the function of which Onias was robbed. In other words, Jesus is invested as the new legitimate high priest, who is to restore to the Temple the priesthood that has been lost for some two hundred years.

Thus Charbonnel suggests the possibility midrashic elaborations on the Name contributed to the very belief in incarnation itself. We know gematria, finding significance in numerical values of the letters of a word, was a special interest among scribes. One scholar who has delved into possibilities here is Bernard Dubourg. In the first volume of L’invention de Jésus he notes that the Hebrew words for “son” and “messiah” have the same numerical value (52) as that of YHWH when the Tetragrammaton is read with the letters themselves spelled out with their names. The Hebrew form of the name “Jesus” likewise has the same value of 52 but only through “the descent of the vowels” (as the ancient scribes would say), or through the “voice” or “the spirit that gives life” to the consonants.

Another midrashic hypothesis relates to the titulus crucis.

Another midrashic hypothesis relates to the titulus crucis.

John 19:19-20

Pilate had a notice prepared and fastened to the cross. It read: JESUS OF NAZARETH, THE KING OF THE JEWS. Many of the Jews read this sign, for the place where Jesus was crucified was near the city, and the sign was written in Aramaic, Latin and Greek.

Charbonnel suggests that here we find another test of the midrashic hypothesis, given that the hypothesis leads us to expect to find clues in the text to alert readers to its midrashic interpretation. One intriguing possibility emerges when Luke’s version is translated into Hebrew:

Luke 23:38

There was a written notice above him, which read: THIS IS THE KING OF THE JEWS.

In Hebrew: zéh hou’ mélech hayehoudyim.

Now the expression ZéH Hou’ is unique in the whole of the First Testament and is found in 1 Samuel 16:12, when Samuel is to designate the king of Israel as the successor of Saul . . . : Jesse sent for him: he (David) was red-haired, with a beautiful look and a beautiful face. And the Lord said, “Go, anoint him: this is he/the one” . . . For Luke, this sign declares to those who are willing to understand that Jesus is the king of the Jews designated by God, like David…

Or one can examine the possible Hebrew behind John’s description:

John 19:19

. . . . It read: JESUS OF NAZARETH, THE KING OF THE JEWS.

| In_Hebrew: | Yehôshoua’ | Hanazir | Wemelekh | Hayehoudim |

| Y | H | W | H |

e

The name of Jesus is developed from YHWH, and perhaps even the sign on the cross identified YHWH.