The author of Acts appears to have used the life experiences, trials and death of Jesus as his model for the life and trials of Paul. The following evidence for this claim is taken from a 1975 article by A. J. Mattill, Jr., “The Jesus-Paul Parallels and the Purpose of Luke-Acts”. If one accepts that the source of Paul’s life and adventures was the Lukan account of Jesus then there are implications for the purpose of Luke-Acts and the literary-theological function of Paul himself.

The first-listed parallels may not seem so striking but keep scrolling. The four trials of each are surely worth noting. Mattill fleshes out many of the points with numerous verbal parallels but I have omitted most of those here.

Contents:

- Law-abiding since infancy

- Preaching work in synagogues

- Support from Pharisees and teaching of resurrection

- Both fulfil scripture in their missions

- Ordained servants to fulfil plan of salvation

- Divine necessity drives both

- Roles of the Spirit, Revelations and Angels

- Similar signs and wonders performed by Jesus and Paul

- Turning to the gentiles

- Journeys to Jerusalem

- Parallel Trials, Charges and Acquittals

- Deaths and resurrections

- Other parallels not in Luke

-o-

Jesus and Paul are from their childhood law-abiding Israelites

|

|

-o-

Jesus and Paul begin and continue their preaching in the synagogues

|

|

A related key parallel:

|

|

-o-

The Pharisees who believe in the resurrection affirm the teachings of Jesus and Paul

|

|

-o-

Fulfilment of Scripture

The author of Luke-Acts based his narrative around the fulfilment of scripture.

Jesus

Jesus quotes and applies Isaiah 6:9-10 to his work and response (Luke 8:10) Jesus proves by Scripture that he is

Jesus affirms from Scripture that the Gospel shall be preached

|

Paul

Paul quotes and applies Isaiah 6:9-10 to his work and response (Acts 28:25-28) Paul proves by Scripture that Jesus is

Paul affirms from Scripture that the Gospel shall be preached

|

-o-

Both are God’s ordained servants to fulfil the divine plan of salvation

| Jesus is God’s chosen servant (Luke 9:35; 23:35)

Jesus is divinely sent (Luke 4:18, 43; 9:48; 10:16)

. Jesus proclaims (Luke 4:18, 19, 44: 8:1)

. attracting multitudes by the message (Luke 5:1; 7:11; 8:4; 11:27, 29; 12:1; 14:25; 19:48; 20:1; 21:38) |

Paul is God’s chosen instrument (Acts 16:17)

Paul is divinely sent (Acts 22:21; 26:17; cf 14:4, 14)

. Paul proclaims (Acts 9:20; 19:13; 20:25; 28:31)

attracting multitudes by the message (Acts 11:26; 13:44; 14:1; 17:4; 19:10) |

-o-

Divine necessity (δει) drives the planned careers of both Jesus and Paul

| Jesus must be in his Father’s house (Luke 2:49)

He must proclaim the good news (Luke 4:43) He must go to Jerusalem (Luke 13:33) He must abide at Zacchaeus’ house (Luke 19:5) In Jerusalem he must suffer many things (Luke 17:25) then he must rise from the dead (Luke 24:7, 26) then he must be received in heaven (Acts 3:21) |

Paul is told what he must do (Acts 9:6)

He must suffer many things (Acts 9:6) He must be delivered from death when cast ashore on a certain island (Acts 27:26) He must see Rome (Acts 19:21) In Rome he must bear witness (Acts 23:11) and there must be judged (Acts 25:10) and must stand before Caesar (Acts 27:24) |

-o-

Spirit, Revelations, and Angels direct, control, assure, strengthen Jesus and Paul

| Jesus receives the Holy Spirit at baptism (Luke 3:21-22)

Jesus is “full of the holy spirit” (Luke 4:1) Jesus is controlled by the spirit — led into wilderness and returns in spirit’s power to Galilee (Luke 4:1, 14) Revelations and voices directing his ministry:

. Angel appears to Jesus in Gethsemane (Luke 22:43) |

Paul receives the Holy Spirit at baptism (Acts 9:17-18)

Paul is “full of the holy spirit” (Acts 9:17; 13:9) Paul is controlled by the spirit — forbidden to enter Asia and Bithynia, purposes in the spirit to go to Jerusalem (Acts 19:6, 7, 21) Revelations and voices directing his ministry:

Angel appears to Paul during storm at sea (Acts 27:23) |

-o-

Parallel signs and wonders confirm the teachings of Jesus and Paul

| Jesus casts out demons (Luke 4:33-37, 41; 8:26-39; 11:20)

Jesus heals the lame man (Luke 5:17-26) Jesus cures many sick (Luke 4:40; 6:17-19) Jesus cures a fever and others stream in for healing (Luke 4:38-40) Jesus raises the dead (Luke 7:11-17; 8:40-42; 49-46) . . . after affirming the person was not really dead (Luke 8:52) Jesus imparts healing power physically (Luke 5:17; 6:19; 8:46) Those healed provide Jesus with necessities (Luke 8:2-3) |

Paul casts out demons (Acts 10:38; 16:16-18)

Paul heals a lame man (Acts 14:8-14) Paul heals many sick (Acts 28:9) Paul cures a fever and others stream in for healing (Acts 28:7-10) Paul raises the dead (Acts 20:9-12) . . . after affirming the person was not really dead (Acts 20:10) Paul imparts healing power physically (Acts 19:6, 11-12) Those healed provide Paul with necessities (Acts 28:10) |

-o-

Turning to the Gentiles is a theme of both Jesus and Paul

| Jesus is rejected and persecuted by his own people from the beginning (Nazareth) of his ministry (Luke 4:28-29)

and often thereafter (Luke 5:21-30; 6:1-5, 6-11; 7:39; 11:14-23, 53-54; 13:14-17; 14:1-6; 15:2; 16:14-15; 19:39-48; 20:1-8, 19-26, 27-40; 22:2-6, 47-53, 66-71; 23:1-43) Jesus is taken outside a city (ἔξω τῆς πόλεως) and threatened with stoning, but escapes with his life (Luke 4:29-30) Audience is enraged when Jesus speaks of gentiles (Luke 4:27-28) Jews lie in wait (ἐνεδρεύοντες) to kill Jesus (Luke 11:54) Jesus declares that just as in days of old Jews to be rejected and gentiles accepted Jesus travels through Samaria (prefiguring Paul) (Luke 9:51-19:44) Jesus sends out the 70 symbolizing the evangelization of every nation (Luke 10:1-16) Teaches the rejection of Israel (Luke 20:9-19) and commands the gentile mission (Luke 24:46-47; Acts 1:8; 22:21) From the Law and Prophets Jesus proclaims the passion, resurrection and ensuing gentile mission (Luke 24:44-47) Jesus proclaims repentance is to be preached to all (Luke 24:47) Jesus is a light revealing salvation to the world (Luke 2:32) |

Paul is rejected and persecuted by his own people from the beginning (Damascus) of his ministry (Acts 9:23)

and often thereafter (Acts 9:23-24, 29-30; 13:45-51; 14:2-6, 19; 17:5-15; 18:6-12; 19:8-9; 20:3; 21:27-23:22; 24:1-9; 28:23-28) Paul is taken outside a city (ἔξω τῆς πόλεως) and stoned by escapes with his life (Acts 14:19-20) Audience is enraged when Paul speaks of gentiles (Acts 18:47-50; 22:21-22) Jews lie in wait (ἐνεδρεύουσιν) to kill Paul (Acts 23:21) Paul declares that just as in days of old Jews to be rejected and gentiles accepted After first preaching to Jews everywhere (Antioch Acts 13:46-47), Corinth (18:6), Ephesus (19:9) and Rome (28:24-28 — quoting Isaiah 6:9-10, cf Luke 8:10) Paul travels through Samaria, reporting how gentiles turned to God (Acts 15:3) . From the Law and Prophets Paul proclaims the passion, resurrection and ensuing gentile mission (Acts 26:22-23) Paul proclaims repentance is to be preached to all (Acts 17:30) Paul is a light revealing salvation to the world (Acts 13:47; 26:23) |

-o-

Journey to Jerusalem and the Passion

The two great travel sections: Luke 9:51-19:44 and Acts 19:21-28:31

Luke 9:51-52 As the time approached for him to be taken up to heaven, Jesus resolutely set out for Jerusalem. 52 And he sent messengers on ahead, who went into a Samaritan village to get things ready for him

Acts 19:21-22 After all this had happened, Paul decided[a] to go to Jerusalem, passing through Macedonia and Achaia. “After I have been there,” he said, “I must visit Rome also.” 22 He sent two of his helpers, Timothy and Erastus, to Macedonia, while he stayed in the province of Asia a little longer.

| A last journey to Jerusalem is a journey toward passion, as prophesied, knowing that he will be handed over to gentiles: (Luke 18:31-33; 9:44)

The ultimate scene of persecution was Jerusalem where the leaders sought his death (Luke 19:47) Jerusalem is the place where prophets must die (Luke 13:33) Jesus is opposed by the Sadducees who deny the resurrection (Luke 20:27) Jesus is accused by the Sadducean high priesthood (Luke 20:27) Jesus delivers farewell addresses (Luke 20:45-21:36; 22:14-38; 24: 36-53) In his last words (Luke 20-22)

Not a hair of your head will perish (Luke 21:18) The Temple is the setting for the prelude to Jesus’ passion (Luke 21:37) Jews plot treachery to kill Jesus (Luke 22:2-6) Jesus is severely tempted to abandon his purpose to die (Luke 22:40-44) — “thy will be done” Jesus is seized at Jerusalem by the Jews (Luke 22:54) Jesus expostulates with his opponents (Luke 22:52-53) |

A last journey to Jerusalem is a journey toward passion, as prophesied, knowing that he will be handed over to gentiles: (Acts 20:22-23; 21:10-11; 28:17)

The ultimate scene of persecution was Jerusalem where the leaders sought his death (Acts 25:2-3) Jerusalem is the place where prophets are expected to die (Acts 21:30-36; 22:22-25; 23:12-22; 25:1-12) Paul is opposed by the Sadducees who deny the resurrection (Acts 23:8) Paul is accused by the Sadducean high priesthood (Acts 23:6-8) Paul delivers farewell addresses (Acts 20:1, 7; 20:18-35) In his last words (Acts 20:18-35)

Not a hair of your head will perish (Acts 27:34) The Temple is the setting for the prelude to Paul’s passion (Acts 21:26) Jews plot treachery to kill Paul (Acts 23:12-16) Paul is severely tempted to abandon his purpose to be ready to die (Acts 21:13; 20:23; 21:4, 10-14) — the Lord’s will be done” Paul is seized at Jerusalem by the Jews (Acts 21:27) Paul expostulates with his opponents (Acts 21:40-22:21) |

-o-

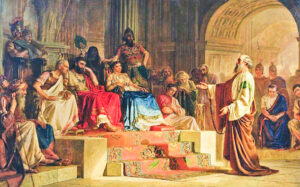

Parallel Trials, Charges and Acquittals

Four trials of Jesus

Jesus is accused of

Pilate asks where Jesus is from and then sends him to the authority (Herod) of that region (Galilee) (Luke 23:6-7)

Roman authority Pontius Pilate finds no guilt in Jesus (Luke 23:4) Pilate exonerates Jesus (“I have found no basis for your charges against this man”) (Luke 23:14) Roman governor Pilate finds Jesus has done nothing worthy of death (Luke 23:15, 22) Pilate would have released Jesus (Luke 23:16, 20) The crowd shout for Jesus’ death (Luke 23:18, 21)

|

Four trials of Paul

Paul is accused of

Felix asks Paul where he is from and then holds him until he can be heard before the relevant authority (Acts 23:34-35)

Roman authority Claudius Lysias finds no guilt in Paul (Acts 23:29) Pharisees exonerate Paul (“we find nothing wrong with this man”) (Acts 23:9) Roman governor Festus finds Paul has done nothing worthy of death (Acts 25:25; 26:31) Agrippa would have released Paul (Acts 26:32) The crowd shouts for Paul’s death (Acts 21:36; 22:22) |

| Jesus was shamefully treated in Jerusalem (Luke 18:32)

Last Supper – take bread, give thanks, break it (Luke 22:19) The people are numbered, Jesus takes bread, gives thanks, breaks bread, feeds the people (Luke 9:12-17) Jesus is accompanied by malefactors (Luke 22:37; 23:32) Jesus kneels to pray (usual posture was to stand) (Luke 22:41) At his trial Jesus is struck by one nearby (Luke 22:63) Jesus is brought before the Sanhedrin “the next day” (not night, as in Mark) (Luke 22:66) Jesus is “delivered up” by Pilate to his captors (Luke 23:25) A crowd follows Jesus (Luke 23:27) |

Paul was shamefully treated at Iconium (Acts 14:5)

Meal aboard ship — take bread, give thanks, break it (Acts 27:33-38) The people are numbered, Paul takes bread, gives thanks, breaks bread, feeds the people (Acts 27:33-38) Paul is accompanied by malefactors (Acts 27:1) Paul kneels to pray (Acts 20:36) At his trial Paul is struck by one nearby (Acts 22:30) Paul is brought before the Sanhedrin “the next day” (Acts 22:30) Paul is “delivered up” by Festus to his captors (Acts 27:1) A crowd follows Paul (Acts 21:36) |

-o-

Paul’s shipwreck and plunging into the deep are the counterparts to Jesus’ death on the cross (Luke 23:26-49; Acts 27:14-24). . . .

Goulder strengthens the argument for the parallel between “Paul’s shipwreck and deliverance and Jesus’ death and resurrection”. To the Semites “death was like going into the sea …. All the sea is death to the Semite, whether we drown or whether we paddle and come out again …” Paul himself refers to his shipwrecks as “deaths” and his rescues as “resurrections” (II Cor. 1:8-10; 11:23)

Going down in a storm was the metaphor par excellence in scripture for death, and being saved from one for resurrection: when St Paul speaks of his shipwrecks in these terms, how can St Luke have thought otherwise ? He has shaped his book to lead up to the passion of Christ’s apostle from xix 21 on in such a way as to recall what led up to the passion of Christ himself in the earlier book: and as the climax of the Gospel is the death and resurrection of Christ, so the climax of Acts is the thanatos and anastasis of Paul.

(Mattill, pp. 19, 21)

| An amazed centurion judges Jesus to be a righteous man (Luke 23:47)

Jesus was three days in the grave (Luke 23:50-56) Jesus was rescued from death (Luke 24:1-11) Post-resurrection joy (Luke 24:12-49) |

An amazed Maltese judges Paul to be a god (Acts 28:6)

Paul was at rest and peace for three winter months cut off from the outside world (Acts 28:1-10) (28:11 – “3 months”) Paul was rescued from death at sea at Malta (Acts 27:39-44) Paul’s voyage to Rome in spring which was Paul’s entrance into a new life (Acts 28:11-16) |

-o-

Other parallels though not in Luke

(If Luke was the last written gospel and its author knew the other three, as some have argued…?)

| Jesus is said to be out of his mind (Mark 3:21)

Jesus is bound (Mark 15:1) Jesus is challenged over disrespect to high priest (John 18:22) Jesus comes before a judge whose wife is mentioned (Matthew 27:19) Jesus’ judges wish to please the Jews (Mark 15:15) Earthquake while on cross (Matthew 27:51) |

Paul is said to be out of his mind (Acts 26:24)

Paul is bound (Acts 21:11, 33; 24:27) Paul is challenged over disrespect to high priest (Acts 23:4) Paul comes before a judge whose wife is mentioned (Acts 24:24) Paul’s judges wish to please the Jews (Acts 24:27; 25:9) Earthquake while in prison (Acts 16:26) |

-o-

Mattill, A. J. “The Jesus-Paul Parallels and the Purpose of Luke-Acts: H. H. Evans Reconsidered.” Novum Testamentum 17, no. 1 (1975): 15–46. https://doi.org/10.2307/1560195 / https://www.jstor.org/stable/1560195

Neil Godfrey

Latest posts by Neil Godfrey (see all)

- Palestinians, written out of their rights to the land – compared with a new history - 2024-10-15 20:05:41 GMT+0000

- The Gospels Versus Historical Consciousness - 2024-10-13 00:48:41 GMT+0000

- “They are Messianic Jewish supremacists, racists, of the worst kind” - 2024-10-07 20:24:10 GMT+0000

If you enjoyed this post, please consider donating to Vridar. Thanks!

Wow!

This is very interesting. I had time only to check a couple of the parallels. One of them “A crowd follows Jesus/Paul” results in opposite emphases. Jesus is mourned, whereas Paul is heckled. Even so, the number and closeness of many of the parallels is striking, and suggests a template that the author or authors might have used. Since it’s usually assumed that it’s the same author, this would have been pretty easy for the Acts author to use.

I also think the comparison can be used to study how “midrash” and intertextuality works in the mind of the ancient author.

Damn. I missed a bit. An hour or so after posting I added another section: Deaths and Resurrections.

As one who is going to be increasingly persuaded by a recent book, I hope that the post is not meant to vehicle implicitly the idea that these parallelisms presuppose one and the same author for “Luke-Acts”. Both the idea and the expression “Luke-Acts” (sic) have to be abandoned, as who argues for Acts of the Apostles being from first century CE.

I am currently persuaded by the view developed by Joseph Tyson https://vridar.org/tag/tyson-marcion-luke-acts/ that our canonical Luke is the product of the author of Acts. The one who wrote Acts was the same who took an earlier form of our Gospel of Luke and augmented it into our canonical form.

Are there Mandaean references to “Christ-Paul” ?

https://www.patheos.com/blogs/religionprof/2016/12/paulish-mistake-mandaean-book-john.html

Haberl in 2014: “The Peacock Angel of the Yezidis is most frequently compared with the figure of Iblis in the Qur’an (7:11–13), but the obvious parallels between the Mandaic Ṭausa and the Yezidi Tawûsê Melek cannot be discounted. As all of the written traditions surrounding the Yezidis and Tawûsê Melek are comparatively late, this account (in the Doctrine of John) may well be considered the earliest surviving tradition about this enigmatic figure.” https://philologastry.wordpress.com/2014/08/14/the-peacocks-lament/

Mandaean references to Christ-Paul? That’s naughty McGrath once more doing his click-bait trick to get people to visit the site of his friend. Haberl, as you no doubt learned, argues emphatically in the negative, no, there are no Mandaean references to Christ-Paul! 😉

Great post and compelling–devastating–establishment of the intentional parallelisms in composition between Paul and Jesus in Luke/Acts especially with reference to the “fateful final trip to Jerusalem”. There has already been work done on the fractured “we” passages of Acts as deriving from an original single travel narrative, “exploded” in Acts with intervening material to spread pieces of the “we” narrative over several years (Niels Hyldahl and others). The close parallelisms between the Luke final journey of Jesus to Jerusalem followed by death and resurrection and the Acts “final journey of Paul to Jerusalem” followed by ending up in Rome … and the Jerusalem-to-Rome leg of that narrative being from the “we” source, suggests a simple observation: since the “we” travel narrative already is jumbled and reworked, having the beginning of the original “we” journey by ship starting from Jerusalem to Rome displaced to be in Acts the final stage, is simply explained in principle.

Then it might be conjectured the other “we” passages in Acts interspersed with various added adventures in Greece and Asia Minor might derive from what in the original “we” source was the return trip from Rome, in Acts situated chronologically the reverse of reality, before the beginning of that “we” trip from Jerusalem to Rome.

Separately, there is independent argument for identifying the “we” trip in Acts, at least the Jerusalem to Rome portion (not certain concerning the return trip back to Judea) with Josephus’s trip to Rome ca. 63 ce, which is important in giving a date to the “we” source. An observation is that there is nothing “Christian” in the original “we” source. The reconstruction would be that all Christian elements in Acts associated with Paul of the “we” source fragment elaborations are overlays or additions, later than the original “we” source of ca. 63.

In my line of reconstruction, Paul does not become a proponent of Jesus as Christ until ca. 70 though I think Paul could have encountered Jesus in a violent episode during the time of the Revolt when Jesus was active in Galilee and (likely) Transjordan (i.e. that there may be something to the Acts story of what Acts and Paul himself in Gal 1 anachronistically presented as his “conversion”), and that all of Paul’s writings postdate 70 ce in date of authorship. But the “we” source from which Acts drew would be glimpses of Paul’s pre-Revolt, pre-Jesus-Christ life history, recast in the later composition of Acts as if Paul was already a Christian. This seems to me a possible fruitful line of reconstruction, in which the Luke/Acts parallels and focus on the pivotal final journey to Jerusalem render explicable how and why the “we” source was fractured and reworked in composition, so as to fit the narrative the author of Luke/Acts wished to construct making Paul like Jesus, and Paul in Rome as parallel to Jesus’s ascension to heaven.

Incidentally I am presenting a paper to the regional Pacific Northwest Society of Biblical Literature, May 21-23, 2021, in the History of Christianity and North American Religions Unit, titled, “Does ‘Aretas’ of 2 Cor 11:32-33 allude to an Aretas V of 69-70 CE?” The abstract:

“A longstanding puzzle has been understanding a reference to a Nabataean ‘governor under king Aretas’ in control of the walls of Damascus at 2 Cor 11:32-33. ‘Aretas’ is universally identified as Aretas IV (ca. 9 bce-39 ce), but the problem is Aretas IV is not known to have controlled Damascus. Several solutions have been offered to reconcile 2 Cor 11:32-33 with known history, all starting from the premise that ‘Aretas’ is Aretas IV. This paper will make the case for a possibility not previously considered: that the reference may be to a previously-unrecognized Aretas V of 69-70 ce.

“A short-lived Aretas V of 69-70 ce is chronologically viable following the death of Malichus II some time in Malichus’s regnal Year 31 of 69-70 (Nisan to Nisan), yet before the beginning of the reign of Rabbel II some time in Rabbel’s Year 1 of 70-71 (Nisan to Nisan). 69-70 was a time when Nabataean forces were actively allied with and provided military units under the direct control of Vespasian and Titus. In that context Roman control of Damascus could have involved Nabataean forces under Roman command such that Paul’s claim to have escaped a commander under king Aretas controlling the walls of Damascus could be other language or circumlocution for Roman control of Damascus in 69-70, in a way that was not the case with Aretas IV. This in turn suggests new possibilities for the relative and absolute datings alluded to in Galatians 1-2.”

I don’t know why we assume there is a lost source behind the “we passages”.

I understand that . . .

— studies have shown that the text around the “we passages” is no different in style from the rest of Acts;

— we can see the prodigious use the author made of creatively adapting gospel and OT material as well as tendentious re-writing of scenes derived from the Pauline epistles, and Josephus, and a little 2 Maccabees, and a dash of Euripides . . . — so much so that one must question whether the author had any other (ostensibly biographical) material to work with (do the we passages add anything beyond these sources?);

— the prologue suggests that the author was a participant among the events he narrates, so when we read “we” in the narrative we recall that the narrative is written by an “I” so it follows that the same “I” is among the “we”.

The “we passages” lend authenticity to the narrative.

Confession: my thoughts are influenced in part by this article:

https://www.academia.edu/43308150/_Did_Luke_Write_Anonymously_Lingering_at_the_Threshold_

A key passage that strikes a harmonious chord to my ears:

Looking forward to notice when your paper is available.

The Arthur Droge article that you cite (“Did ‘Luke’ Write Anonymously? Lingering at the Threshold”, pp. 495-518 in Die Apostelgeschiche im Kontext und fruhchristlicher Historiographie, ed. Frey, Rothschild and Schroter, Berlin: de Gruyter, 2009), and your argument, makes what seems like a compelling, conclusive argument, essentially: (1) Luke/Acts is 2nd ce and the author was not a personal associate or eyewitness of Paul; yet (2) the author of Acts intends the reader to understand that the “we” of the “we” passages refers to himself; and (3) the “we” passages of Acts are either written in or are difficult to distinguish from the author’s style. Therefore (4) the entire thing is fiction–intentionally deceptive fiction–from the author of Luke/Acts. The “we” is a subtle fictitious literary device of the author, for the purpose of lending authenticity to the narrative.

The argument hangs together, and you develop it well, and my delay in responding was because of revisiting thinking and reading prompted by your comment. In the end I see a differing reconstruction–accounting for the same facts–as not only viable but subjectively more likely, without claim that evidence excludes the reconstruction or reading of Droge/you. Of the above four points, I agree that the first three are facts, not contested. On the fourth, I agree the author is being intentionally deceptive in having the reader understand “we” to be him, when that was not and cannot have been the case. The only issue with respect to the fourth point is whether the author created the “we” material de novo out of whole cloth, or worked over a prior written source with the same literary purpose intended. Either way it does not matter for the reading and intent of Acts in its published form in its 2nd ce context, but it may matter to us with respect to Christian origins history questions. The unresolved question is sources: did the author of Acts use sources? Was the author of Acts creating new fiction in the “we” passages out of whole cloth, or on the other hand reworking written sources creatively in the production of Acts?

As you cite the influence on you of the Droge article (making the case for de novo whole-cloth creation of the “we” material), I am influenced by this article with a different interpretation of the same data, arguing for a source-development reconstruction in explanation of the final form of Acts: Justin Taylor, “The Making of Acts: A New Account”, Review biblique 97 (1990): 504-524.

I have gone over the Justin Taylor article again prompted by your comment and by the Droge article, and although the source reconstruction of Boismard and Lamouille discussed by Taylor is unavoidably hypothetical, it makes sense to me in its major points as at least a viable theory–above all, gives a plausible mechanism of how doublets in Acts appear, both versions deriving from the same source. I do think there may be one significant error however. Boismard/Lamouille/Taylor interpret the “we” passages as deriving from a source which originally was of a single voyage by ship and on land (so far so good, that was also Hyldahl’s argument, not the case in final-form Acts), but they identify that voyage as the same as “collection for the saints in Jerusalem” of the epistles, whereas the line of reconstruction I see is that the ship voyage of the “we” source was pre-70 and the era of writing of the epistles/collection for the saints in Jerusalem was later and unrelated, post-70. That the author of Acts intended, and deceptively so, the reader to read “we” as the author himself is unchanged from what Droge and you see. Only the backstory leading up to the final form of Acts as we see it differs in reconstruction or explanation thereof.

On another point, the reading I have suggested of Gal 2:1, gr. dia, as an event occurring “during” the fourteen-year period of that verse instead of “after” as universally translated in modern translations and scholarly understanding–and that the endpoint of the fourteen years is not the visit to Jerusalem but the time of writing of the letter to the Galatians–seemingly idiosyncratic in going against prevailing scholarly reading–I have found in fact has received a serious published argument in this article: Alexis Bunine, “La date de la premiere visite de Paul a Jerusalem (suite et fin)”, Revue biblique 113 (2006): 601-622 at 620-621. This is the best explanation of the case for this different reading of the syntax of Gal 2:1 in print to my knowledge. Ironically Bunine develops that syntactic argument for the purpose of solving a problem which I think is a non-issue, but never mind that, the argument itself for “during” rather than “at the end of” I believe is sound.

Thank you so much for this detailed response, Greg. You certainly keep giving me new angles to think about. I have since added Bunine to my collection and have read his argument re “dia” the 14 years — indeed most interesting. I’ll continue my exploration of the letters of Paul from a different perspective but always with your alternative standing beside me. I look forward to your full explanation of the date of Paul and Aretas.

Great post.

A query: in the post you say, “If one accepts that the source of Paul’s life and adventures was the Lukan account of Jesus then there are implications for the purpose of Luke-Acts … ”

Do you mean, ‘the Lukan account of Jesus’ in Acts or in Luke, or in both ie. in Luke_Acts ?

I was thinking of the Jesus of the Gospel of Luke, and by extension, the Jesus of his source gospels, too — those of Mark and Matthew.

Thanks for the prompt reply Neil.

Then … If one accepts that the source of Paul’s life and adventures was the synoptic gospel accounts of Jesus then are there implications for the relative dating of the Pauline letters and of the synoptic gospels? ie. could some, at least, of the Pauline letters be dated to around the time that early manifestations of the synoptic gospels were being written?

Your first question was easy to answer. This second one is hard. Though if I focus on your word “could” then I can opt for an easy way out — yes, anything’s possible. More meaningful probabilities on the basis of demonstrable evidence are ideas I am still wondering about and keeping in mind as I try to read more (hopefully) relevant material.

I hope to be posting more about Paul’s letters and ideas this year. Still much to learn first.

If it helps, here is a link

https://scholar.csl.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1002&context=ofs

The New Perspective from Paul

What I’m looking at at this moment are the different ways Paul’s letters, in style and content, fit wider literary cultures. Main focus is on ancient philosophical literature, especially letters, on the one hand, and comparison with the structures and motifs in the Jewish scriptures on the other. I’m finding it increasingly difficult to see the letters of Paul as the work of “a historical Paul” as we generally understand him.