The old is dying and the new cannot be born; in this interregnum a great variety of morbid symptoms appear. — Gramsci

We now come to Nancy Fraser’s analysis (Gramchi) of Trump as President, hence the title adjustment. Previous posts in the series:

Gramsci’s theory of hegemony

Nancy Fraser’s perspective builds on the concept of hegemony as developed by Antonio Gramsci, an Italian Marxist who died in a Mussolini prison. Put simply, hopefully not too simply, the idea of hegemony is that a ruling class needs to make its worldview and values the worldview and values of the groups it dominates. Simply owning the wealth and all the businesses and factories etc is not enough to maintain control. The subordinate classes must accept the belief systems of their rulers for the system to work smoothly. The ruled must accept that their world and their place in it is only natural and commonsensical.

Fraser identifies two types of common sense values that the upper classes expect those they dominate to accept:

- they must share a common belief in what is right and fair regarding wages, wealth and ability to get ahead, job status and opportunities, or in other words, a common belief in what is fair and right concerning the distribution of the wealth accumulated within the society;

- they must share a common belief in what is right and fair regarding respect and status, personal recognition and esteem, and who has a right to be a part of recognized elites.

That Election

The progressive populist movement led by Bernie Sanders was desperately knocked out of the race by the establishment elites in the Democratic Party. Rules changes, finding ways to ensure the populist leader’s superior popular support did not win the day, enabled the party machine to position a comparatively unpopular leader who represented the prevailing neoliberal establishment to take on Trump.

As we saw in the previous post significant segments of Sander’s supporters felt the other populist leader was preferable to Hillary Clinton. The reactionary populist victory surprised many though not all observers.

Bait and Switch

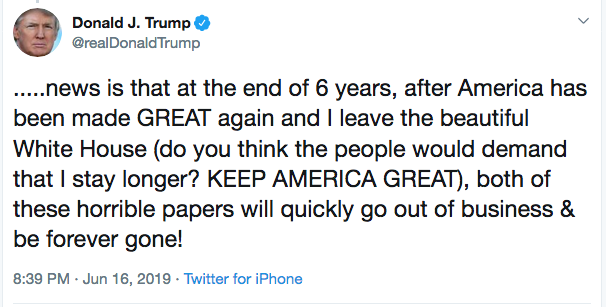

Just as Obama had disappointed his voters by failing to capitalize on his Occupy Wall Street popularity and begin to turn the nation’s back on neoliberalism as we covered in the previous post, Trump also did what so many politicians do: he turned his back on his promises to take on the big business powers who were hurting the ordinary person and to undertake programs to restore employment and job security. In Gramsci’s terms, he abandoned the populist distributive policies (wealth distribution) he had promised. He added insult to injury open displays of “crony capitalism and self-dealing”.

Granted, he canceled the Trans-Pacific Partnership. But he has temporized on NAFTA and failed to lift a finger to rein in Wall Street.

Nor has Trump taken a single serious step to implement large-scale, job-creating public infrastructure projects; his efforts to encourage manufacturing were confined instead to symbolic displays of jawboning and regulatory relief for coal, whose gains have proved largely fictitious.

And far from proposing a tax code reform whose principal beneficiaries would be working-class and middle-class families, he signed on to the boilerplate Republican version, designed to funnel more wealth to the one percent (including the Trump family).

As this last point attests, the president’s actions on the distributive front have included a heavy dose of crony capitalism and self-dealing. But if Trump himself has fallen short of Hayekian ideals of economic reason, the appointment of yet another Goldman Sachs alumnus to the Treasury ensures that neoliberalism will continue where it counts.

(my formatting and bolding in all quotations of Nancy Fraser)

But why didn’t his backers rise up in protest over such a blatant betrayal? It is as if they didn’t even notice what he’d done. But as we shall see some are beginning to notice and realize that their conditions are not improving.

That’s where the second half of Gramsci’s analysis, the rhetoric of recognition values, enters.

Having abandoned the populist politics of distribution, Trump proceeded to double down on the reactionary politics of recognition, hugely intensified and ever more vicious.

I’m reminded of the tired old countless “classic” cases throughout history and the world today of political leaders raging and foaming bile against outsiders or minorities within to deflect attention from their own failings or ineptitude. No doubt they are sincere. They have to believe their own rhetoric, at least at the time they are saying it, to impress their audience with their “sincerity”.

Having abandoned the populist politics of distribution, Trump proceeded to double down on the reactionary politics of recognition, hugely intensified and ever more vicious. The list of his provocations and actions in support of invidious hierarchies of status is long and chilling:

- the travel ban in its various versions, all targeting Muslim-majority countries, ill disguised by the cynical late addition of Venezuela;

- the gutting of civil rights at Justice (which has abandoned the use of consent decrees) and at Labor (which has stopped policing discrimination by federal contractors);

- the refusal to defend court cases on LGBTQ rights;

- the rollback of mandated insurance coverage of contraception;

- the retrenchment of Title IX protections for women and girls through cuts in enforcement staff;

- public pronouncements in support of rougher police handling of suspects, of “Sheriff Joe’s” contempt for the rule of law, and of the “very fine people” among the white-supremacists who ran amok at Charlottesville.

The result is no mere garden-variety Republican conservatism, but a hyper-reactionary politics of recognition.

Examples, as we know, have multiplied since Fraser’s article was sent to the publisher.

Altogether, the policies of President Trump have diverged from the campaign promises of candidate Trump. Not only has his economic populism vanished, but his scapegoating has grown ever more vicious. What his supporters voted for, in short, is not what they got. The upshot is not reactionary populism, but hyper-reactionary neoliberalism.

New evidence that Trump is losing support even among his base: Trump Fires His Pollster After Polls Show Him Losing In Every Critical State

Since Nancy Fraser’s article was published we have seen further tensions between Trump and his supporters, both business and some of the working class, over his tariff war with China. Tariffs, of course, hurt both businesses and consumers, contrary to Trump’s rhetoric.

Trump is now “ruling” (an appropriate word, I think, given his defiance of Congress — and Congress’s failing to seriously challenge him — in recent weeks) without a coherent or stable hegemonic bloc. His hyper-reactionary neoliberalism does not allow for that. His personal manner does not allow him to work with a trusting and professionally minded team. He relies upon the Republican Party but the Republican Party is far from outspokenly unanimous in their support for him. It appears that many Republicans would like to take back control but are a loss to know how. What we have seen from the White House are chaos, contradictory comings and goings, statements and counter-statements.

Nancy Fraser admits that we have no way of knowing where all of this is going to lead and wonders if there will be a split in the Republican Party. The U.S. is now in a position of another hegemonic vacuum, or at least bereft of a secure one. Recall that it was the hegemonic vacuum — no-one in power to address the problems of declining incomes, joblessness, rise of debts — that led to Trump to begin with.

But there is also a deeper problem. By shutting down the economic-populist face of his campaign, Trump’s hyper-reactionary neoliberalism effectively seeks to reinstate the hegemonic gap he helped to explode in 2016. Except that it cannot now suture that gap. Now that the populist cat is out of the bag, it is doubtful that the working-class portion of Trump’s base will be satisfied to dine for long on (mis)recognition alone.

Back to the gap, the condition that led to Trump in the first place. Infrastructure spending and job creation, serious tax reform and healthcare . . . the policies that were meant to seriously address the breakdown in living standards for his base and all the working and middle class are nowhere in sight. (Though he did say he would work on healthcare more in his next term, right?) Meanwhile, the rhetoric distracts from the wealth distribution failure.

Since the appearance of Fraser’s article the US economy has not significantly improved at all. His supporters have not benefited materially despite his boasts of “the greatest economy ever.” See Why Trump Gets a ‘C’ on the Economy: Forget His Boasts; Growth Is Just Average and Well Behind Reagan, Clinton, Even Carter on David Cay Johnston’s DCReport.

Preparing for More Dangerous Trumps

The potential opposition to Trump is divided. “Diehard Clintonites” remain as opposed to the progressive populist bloc marshalled in support of Sanders. And,

complicating the landscape is a raft of upstart groups whose militant postures have attracted big donors despite (or because of) the vagueness of their programmatic conceptions.

(Americans and others will be more aware of the groups Fraser refers to here than I am.)

Another serious rupture Fraser identifies is division among the Democrats over whether to dedicate themselves to policies framed around

- class — that is, to concentrate on winning back the white working class vote that deserted to Trump after Sanders was set aside by Clinton

or

- race — to fiercely oppose white supremacy and win the votes of blacks and Latinos.

The division is serious and agonizing insofar as the two problems really need to be addressed together, not either/or, as Fraser comments.

Fraser’s concern is that if the Democrats do focus on winning back the erstwhile working class Sanders’ supporters the real victor will be the traditional status quo, the same old distributive values of the neoliberals who have established the “regressive economy” in favour of the 1%. It will be a return in some form to the same old progressive liberalism: maintain the economic system and embrace the rhetoric of militant anti-racism.

In other words, the surely inevitable result of such a development would be to turn potential Democrat supporters to Trump instead.

Another dire consequence would be that the Democrats led by Clintonite neoliberals would

effectively join forces with [Trump] in suppressing alternatives to neoliberalism—and thus in reinstating the hegemonic gap.

As noted above, we then come circle back to the very conditions that created Trump. The “hegemonic gap”, with no-one in the political system addressing the “regressive economy”, with both sides entrenching the very problems that have led to both the progressive and regressive populist movements.

To reinstate progressive neoliberalism, on any basis, is to recreate—indeed, to exacerbate—the very conditions that created Trump. And that means preparing the ground for future Trumps—ever more vicious and dangerous.

The Solution

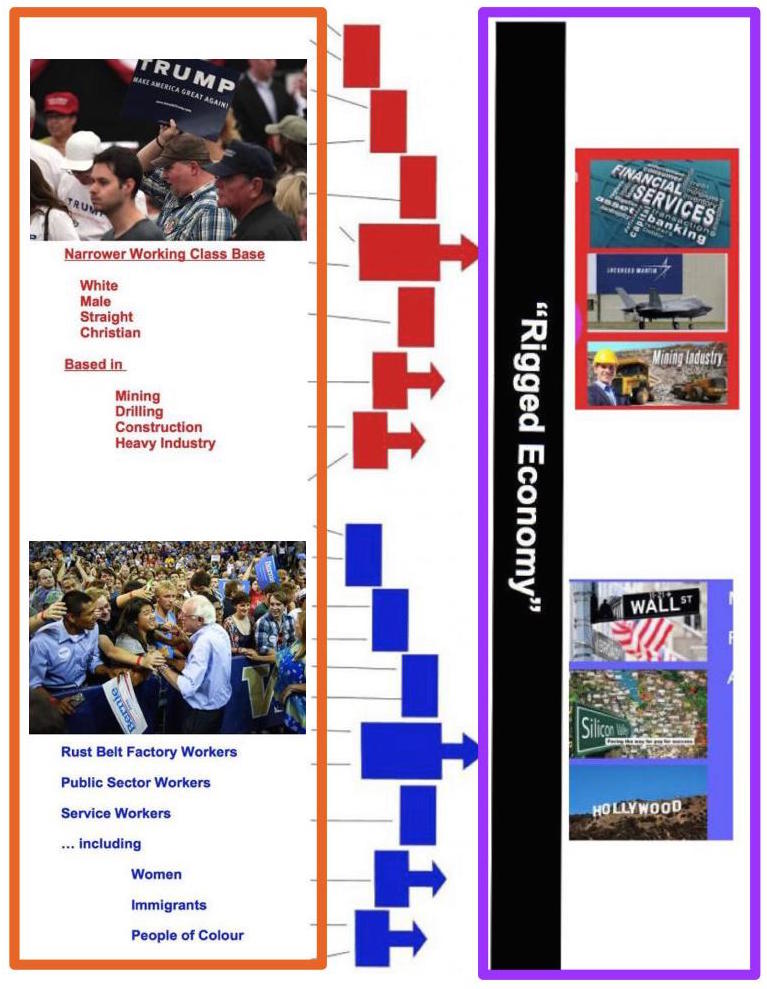

working-class supporters of Trump and of Sanders would have to come to understand themselves as allies—differently situated victims of a single “rigged economy,” which they could jointly seek to transform

The solution is to organize a wide-based popular bloc that will oppose the neoliberal powers (global finance, responsible for the problems of financialization, deindustrialization and corporate globalization) that both the Clintonites and Trump serve. Currently, neither bloc of progressive or regressive populists

is currently in a position to shape a new common sense. Neither is able to offer an authoritative picture of social reality, a narrative in which a broad spectrum of social actors can find themselves. Equally important, neither variant of neoliberalism can successfully resolve the objective system blockages that underlie our hegemonic crisis.

So the crises of debts, climate change, stresses on community life continue.

A broad bloc cannot come from Trump’s reactionary populism. Its values of recognition exclude large sectors of the population. That movement is not going to attract those working and middle class families who rely upon service work, agriculture, domestic labour and the public sector. Those sectors employing large numbers of women, immigrants and people of colour are the ones Trump is targeting.

The recognition values of the progressive Sanders bloc are at least seek to be inclusive. Is it possible for them to win over Trump supporters in an anti-neoliberal alliance that targets the institutions responsible for their crises.

But They Hate Each Other

We know the obstacle to such an alliance:

the deepening divisions, even hatreds, long simmering but recently raised to a fever pitch by Trump, who, as David Brooks perceptively put it, has a “nose for every wound in the body politic” and no qualms about “stick[ing] a red-hot poker in [them] and rip[ping them] open.”

The result is a toxic environment that appears to validate the view, held by some progressives, that all Trump voters are “deplorables”—irredeemable racists, misogynists, and homophobes. Also reinforced is the converse view, held by many reactionary populists, that all progressives are incorrigible moralizers and smug elitists who look down on them while sipping lattes and raking in the bucks.

Continuing . . . .

Fraser, Nancy. 2017. “From Progressive Neoliberalism to Trump—and Beyond.” American Affairs Journal 1 (4): 46–64. https://americanaffairsjournal.org/2017/11/progressive-neoliberalism-trump-beyond/

Like this:

Like Loading...