I have belatedly caught up with some of Nancy Fraser‘s analysis of the current worldwide political condition that has seen Trump in the US and a rise in ethnocentric and authoritarian movements worldwide and I’d like to try to set out her ideas over a few posts here as I find opportunity. Above all, I’d like to try to simplify Nancy Fraser’s articles that come across to me at an overly high conceptual level. (If anything in this series of posts is not clear or accurate then I expect to be called to account.) Gramsci was criticized (while also being highly honoured) by Noam Chomsky for his obscure intellectual jargon. Given that Fraser acknowledges a debt to Gramsci it may not be surprising that she also writes above the level of everyday language that is always clear to all. I think Fraser’s analysis is correct, or at least among the most explanatory that I have heard for making sense of the situation of the world today and how someone like Trump is where he is now. These posts will be extracted from the points made by Nancy Fraser in . . .

The crisis is global

- In the USA we see Trump

- In the UK we have the Brexit debacle

- In the European Union we have the disintegration of the social-democratic and centre-right parties that had been its mainstay

- Throughout northern and east-central Europe we have been witnessing the rise of racist, anti-immigrant parties

- In Latin America, Asia, the Pacific we have seen the rise of authoritarian (proto-fascist) forces.

The above changes all share one thing in common:

All involve a dramatic weakening, if not a simple breakdown, of the authority of the established political classes and political parties. It is as if masses of people throughout the world had stopped believing in the reigning common sense that underpinned political domination for the last several decades. It is as if they had lost confidence in the bona fides of the elites and were searching for new ideologies, organizations, and leadership. Given the scale of the breakdown, it’s unlikely that this is a coincidence. Let us assume, accordingly, that we face a global political crisis.

So it is fair to look for something that is happening on a global scale to explain the above retrograde shifts.

And it’s not just political. It involves serious ecological, social and economic stresses. Some of the major challenges within the US have been

- the changing nature of the finance industry;

- the proliferation of precarious service-sector McJobs;

- ballooning consumer debt to enable the purchase of cheap stuff produced elsewhere;

- conjoint increases in carbon emissions, extreme weather, and climate denialism;

- racialized mass incarceration and systemic police violence;

- and mounting stresses on family and community life thanks in part to lengthened working hours and diminished social supports.

It’s about time the above stresses had a serious impact on the politics of countries where they are found together. And we have seen the first political “blowback” of these stresses in the U.S. with the rise of Trump.

But how was it, exactly, out of all of the above, that the Trump presidency came about?

How the ruling class rules

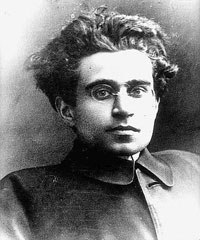

Nancy Fraser’s perspective builds on the concept of hegemony as developed by Antonio Gramsci, an Italian Marxist who died in a Mussolini prison. Put simply, hopefully not too simply, the idea of hegemony is that a ruling class needs to make its worldview and values the worldview and values of the groups it dominates. Simply controlling the wealth and all the businesses and factories etc is not enough to maintain control. The subordinate classes must accept the belief systems of their rulers for the system to work smoothly. The ruled must accept that their world and their place in it is only natural and commonsensical. The term hegemony implies ruling by attaining the willing consent of the lesser powers. If there is consent then what is the problem? Read on to see.

Fraser identifies two types of common sense values that the upper classes expect those they dominate to accept:

- they must share a common belief in what is right and fair regarding wages, wealth and ability to get ahead, job status and opportunities, or in other words, a common belief in what is fair and right concerning the distribution of the wealth accumulated within the society;

- they must share a common belief in what is right and fair regarding respect and status, personal recognition and esteem, and who has a right to be a part of recognized elites.

In other words, the owners of the wealth, or the owners of all the businesses that produce that wealth (mining companies, service industries, etc) must form an “ideological” or “belief system” bond with those they wish to rule. Their position of power would not be very secure otherwise.

Values pertaining to Recognition

Leaders of a certain sector of the U.S. economy positioned themselves as promoters of human rights. The “most dynamic, high-end “symbolic” and financial sectors of the U.S. economy” — Wall Street, Silicon Valley, and Hollywood — embraced the values of feminism, antiracism, multiculturalism, environmentalism, and LGBTQ rights that had been emerging out of progressive liberal activist movements from the 1960s and 70s. These values served the interests of both classes: “Sure, we believe in equal opportunity rights for women, blacks, gays — we want the very best talent from any quarter to get to the top and make the most of their (not to mention our corporate) potential” (my paraphrase).

Anyone who was capable of doing a job should be given the opportunity to do that job regardless of their race, gender, etc. It was a subtle form of meritocracy to see who was worthy of class advancement.

And that ideal was inherently class specific: geared to ensuring that “deserving” individuals from “underrepresented groups” could attain positions and pay on a par with the straight white men of their own class.

The progressive-neoliberal bloc combined an expropriative, plutocratic economic program with a liberal-meritocratic politics of recognition.

Values pertaining to Distribution

Here is where the Left divided. Large sectors of the Left were seduced into supporting the other set of values (concerning distribution of wealth) of those economic leaders. Continue reading “Understanding the Rise of Trump (1)”