Continuing the series based on the article by Nancy Fraser. Previous posts:

–o–

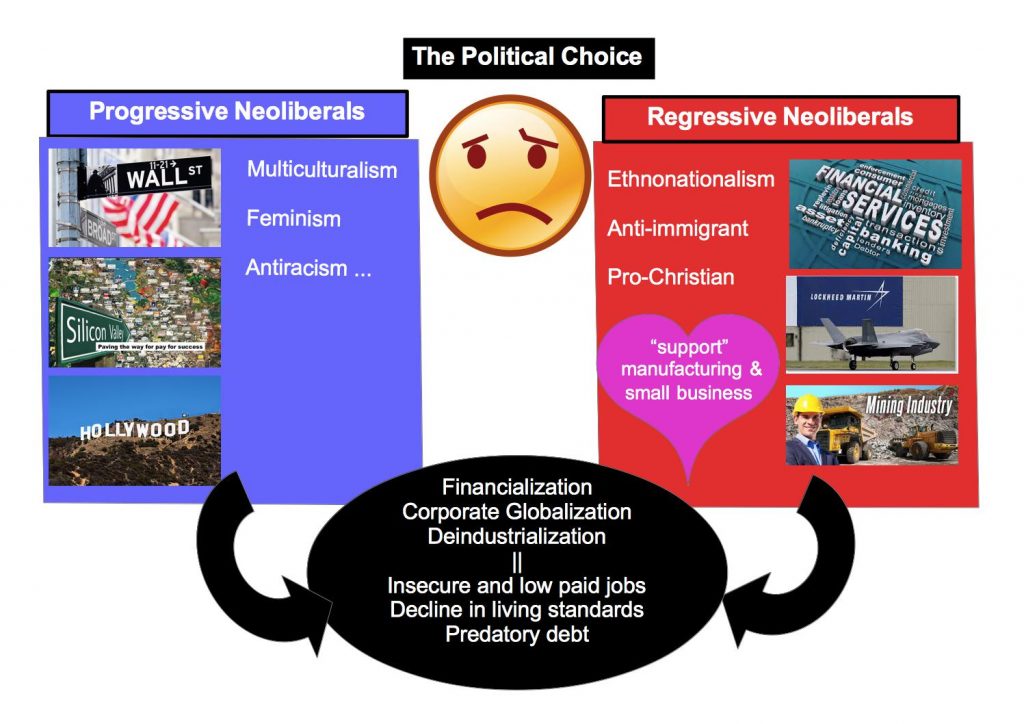

There was no force in politics to oppose the eroding of working and middle class standards of living. Anti-liberal voices were excluded from respectable public debate. Hence what Fraser terms “the hegemonic gap and the struggle to fill it”.

Only a matter of time

Given that neither of the two major blocs spoke for them, there was a gap in the American political universe: an empty, unoccupied zone, where anti-neoliberal, pro-working-family politics might have taken root. Given the accelerating pace of deindustrialization, the proliferation of precarious, low-wage McJobs, the rise of predatory debt, and the consequent decline in living standards for the bottom two-thirds of Americans, it was only a matter of time before someone would proceed to occupy that empty space and fill the gap.

Hope for change 1: Obama

2007: U.S. facing one of its worst ever foreign policy disasters (Iraq War); and worst financial crisis since the Great Depression, “and a near meltdown of the economy” — An African American speaking of hope and change, vowing to “transform not just policy but the entire ‘mindset’ of American politics became president.

But rather than mobilize his mass support to turn away from neoliberalism he entrusted economic recovery to the same Wall Street forces that had almost wrecked it. He gave cash bailouts to the banks but nothing comparable for the tens of millions of the banks’ victims who lost their homes.

The single genuine benefit he gave the working class was an expansion of Medicaid through the Affordable Care Act. But that was the exception.

All told, the overwhelming thrust of his presidency was to maintain the progressive neoliberal status quo despite its growing unpopularity.

Hope for change 2: Occupy Wall Street

2011: I got a frisson of excitement when these protests broke out. “Please let them spread!” Having given up hope that the political system was going to respond to the economic crisis without some prodding small groups throughout the U.S. seized control of public spaces “in the name of the 99%”. They were protesting against a system that “pillaged the vast majority in order to enrich the top one percent”. Some polls estimated that up to 60% of the American public came to sympathize with these protesters.

So what happened? Obama picked up on the rhetoric of the Occupy Wall Street movement, promising great change for his second term. But after winning the election of 2011 . . . .

Having won himself four more years, however, the president’s newfound class consciousness swiftly evaporated. Confining the pursuit of “change” to the issuing of executive orders, he neither prosecuted the malefactors of wealth nor used the bully pulpit to rally the American people against Wall Street. Assuming the storm had passed, the U.S. political classes barely missed a beat. Continuing to uphold the neoliberal consensus, they failed to see in Occupy the first rumblings of an earthquake to come.

(I’m reminded of Australia’s recent royal commission into the banking, superannuation and financial services industries. The terms of the investigation only allowed a limited area of questionable practices to be scrutinized but the results even of that much led to much outraged publicity and all the appearances of strong mea culpas from the banks and the most sincere promises to reform and win back trust. Within a few months of the commission winding up and the promises to do better still ringing in our ears, several banks responded to the Reserve Bank’s lowering of interest rates by adding to the pockets of the CEOs and refusing to pass on the full benefit to their customers.)

The Earthquake

That earthquake finally struck in 2015/16, as long-simmering discontent suddenly shape-shifted into a full-bore crisis of political authority.

In that election season, both major political blocs appeared to collapse.

On the Republican side, Trump, campaigning on populist themes, handily defeated (as he continues to remind us) his sixteen hapless primary rivals, including several handpicked by party bosses and major donors. On the Democratic side, Bernie Sanders, a self-proclaimed democratic socialist, mounted a surprisingly serious challenge to Obama’s anointed successor, who had to deploy every trick and lever of party power to stave him off. On both sides, the usual scripts were upended as a pair of outsiders occupied the hegemonic gap and proceeded to fill it with new political memes.

(For the concepts of hegemony and counter-hegemony refer to the first post in this series.)

Both Sanders and Trump excoriated the neoliberal politics of distribution. But their politics of recognition differed sharply.

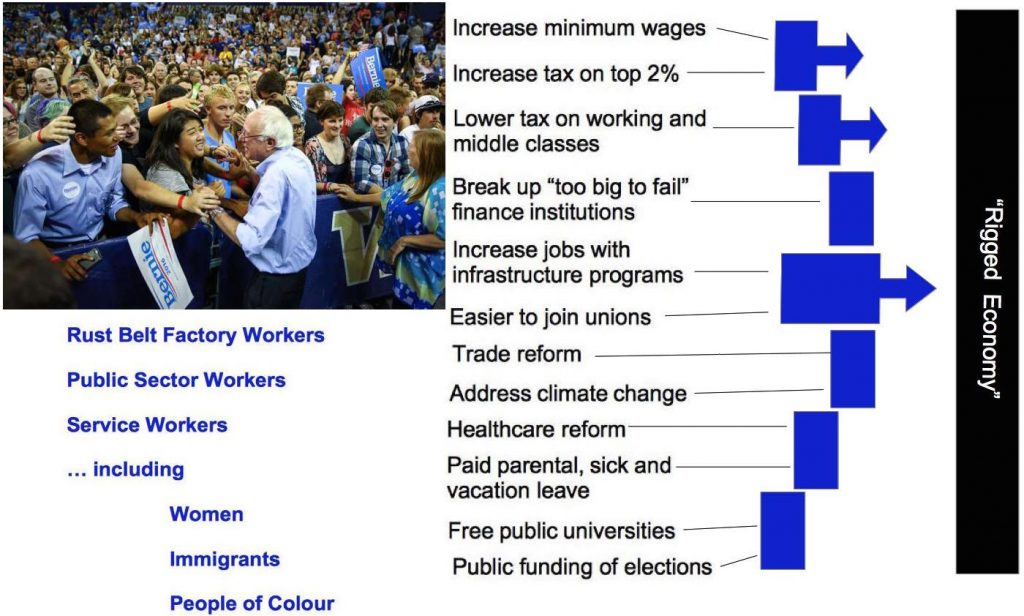

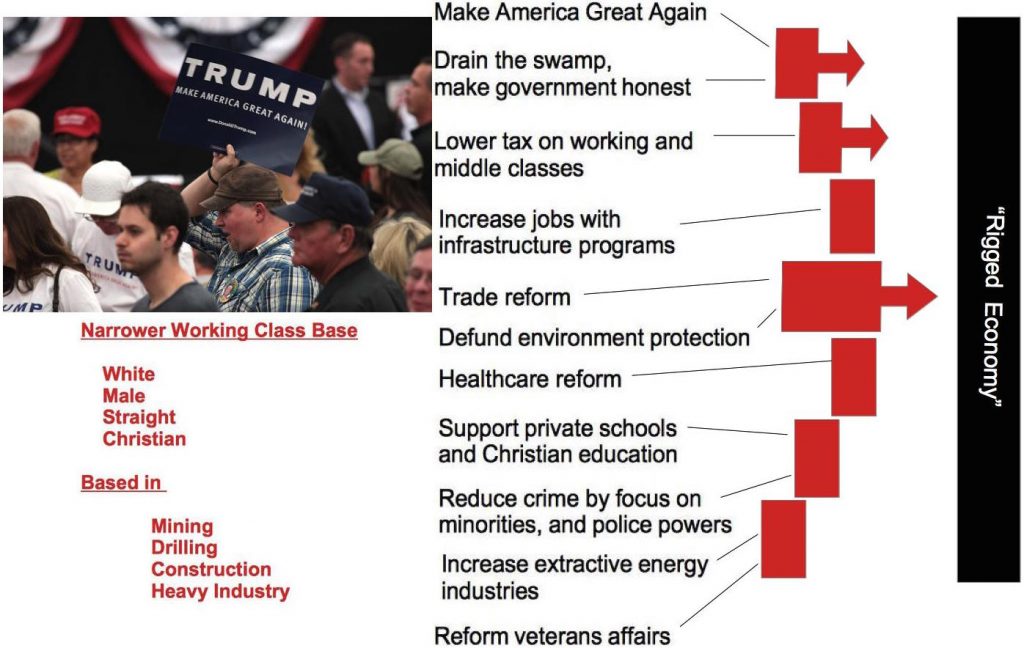

Whereas Sanders denounced the “rigged economy” in universalist and egalitarian accents, Trump borrowed the very same phrase but colored it nationalist and protectionist. Doubling down on long-standing exclusionary tropes, he transformed what had been “mere” dog whistles into full-throated blasts of racism*, misogyny, Islamophobia, homo- and transphobia, and anti-immigrant sentiment. The “working-class” base his rhetoric conjured was white, straight, male, and Christian, based in mining, drilling, construction, and heavy industry. By contrast, the working class Sanders wooed was broad and expansive, encompassing not only Rust Belt factory workers, but also public-sector and service workers, including women, immigrants, and people of color.

(Trump flatly denied he is racist (and misogynist…) but see Strategies of Denial of Racism for an analysis of how racist attitudes and policies have been subsumed under the rhetoric of denialism since the Civil Rights movement of the 1960s.)

The diagrams below represent the general picture. Most Sanders’ supporters were young and college educated but Sanders also had strong support among “eviscerated manufacturing centers” who had earlier voted for Obama. (The respective working class supporters were not strictly divided into the groups listed; there were fuzzy areas of overlap, of course.)

Both Sanders and Trump attacked the neoliberal politics of distribution, of the 1%’s plundering of the rest. But they diverged in their recognition values.

Counter-hegemony of progressive recognition

Sanders’ was building a broad, expansive working-class base for a counter-hegemony to the “rigged economy” of the prevailing hegemony of the neoliberal/corporate powers. His “recognition values” (see the first post to understand how recognition values work in establishing political dominance, how they represent a faction’s “common sense” view of the world) acknowledged the right of all not only manufacturing workers but public sector and service workers to be restored to a more prosperous position. Recognition was extended to women, immigrants, LGBTQ, people of colour, immigrants. It was a progressive populist foundation for a broad counter-hegemony indeed.

Counter-hegemony of reactionary recognition

Trump’s supporters came from those same gutted manufacturing regions, including from those who had earlier supported Sanders against Hillary Clinton in the Democratic Primaries. His supporters also included dyed in the wool Republicans libertarians, small business owners, others with “little interest in economic populism.”

Trump’s counter-hegemonic bloc was a reactionary populism fueled by a “hyper-reactionary politics of recognition”. Trump’s recognition went to Christians who opposed abortion and the teaching of evolution in school; to the veterans of America’s wars; to those who felt threatened by immigrants; to those who saw people of colour as a primary source of crime and those who wanted fewer controls on police powers; to those who had been hurt financially by the demise of manufacturing industries. (I have strayed somewhat from the strict letter of Fraser’s article but think I have retained the gist.)

The next stage of the Trump narrative is how after he was elected President he abandoned his attack on the “rigged economy”, the neoliberal view of wealth distribution, while at the same time ratcheting up his hyper-reactionary recognition message.

Continuing…..

Fraser, Nancy. 2017. “From Progressive Neoliberalism to Trump—and Beyond.” American Affairs Journal 1 (4): 46–64. https://americanaffairsjournal.org/2017/11/progressive-neoliberalism-trump-beyond/

Neil Godfrey

Latest posts by Neil Godfrey (see all)

- What Others have Written About Galatians (and Christian Origins) – Rudolf Steck - 2024-07-24 09:24:46 GMT+0000

- What Others have Written About Galatians – Alfred Loisy - 2024-07-17 22:13:19 GMT+0000

- What Others have Written About Galatians – Pierson and Naber - 2024-07-09 05:08:40 GMT+0000

If you enjoyed this post, please consider donating to Vridar. Thanks!

According to Polybius’ (born around 200 BC) doctrine of anacyclosis, all constitutional development is in a circle, and democracybeing inherently weak and unstable, will tend to degenerate into the “malignant” political orders of tyranny, oligarchy, and ochlocracy.

I’ve been a lifelong member of the Democratic Party, and it wasn’t until Obama that I realized how far the party had diverged from the legacy of Franklin Roosevelt, Harry Truman, John Kennedy, and Lyndon Johnson with regard to domestic policy aimed at allowing the working class to share in the wealth they create through their labor.

Occupy Wall Street and Bernie Sanders give me hope that there are a substantial number of people in this country who are not complacent about how the political elites have been working against the interests of the rank and file members of the public.

If Nancy Fraser’s analysis is sound it looks like the US is in for a very traumatic time, very serious — unless someone can bring the two populist movements together. It looks like the Democrats have lost the plot, as you say.