The first part of my response to Tim O’Neill’s Jesus the Apocalyptic Prophet is @ Examining the Evidence for Jesus as an Apocalyptic Prophet. There we pointed out that there is no support in our historical sources (primarily Josephus) for the common assertion that Judaeans and Galileans in the early first century were pining for an imminent overthrow of Roman rule and the establishment of a liberating Kingdom of God. In other words, the assertion that apocalyptic prophets like our gospel depictions of John the Baptist and Jesus would have been enthusiastically welcomed at that time lacks evidence.

This post addresses one more significant but (as I hope to demonstrate) flawed plank in O’Neill’s argument. I expect to address one more final point in the Apocalyptic Prophet essay in a future post.

Tim O’Neill begins the next step of his argument with the following verse and without identifying the source of his translation:

“Has come near”, as we shall see, is a disputed translation. But O’Neill is confident that his translation is the correct one, and he even asserts without reference to any evidence that Jesus was speaking of a soon-to-be end of human oppression, not just demonic rule:

The writer of gMark does not depict Jesus explaining what he means and expects his audience to understand – here Jesus is proclaiming that the expected end time had come, that the kingship of God was close and that those who believed this and repented would join the righteous when the imminent apocalypse arrived. Far from being a prophet of doom, Jesus is depicted proclaiming this imminent event as “good news” – the relief from oppression, both human and demonic, was almost here.

Towards the end of his post O’Neill does acknowledge that some scholars do dispute the translation but he sidelines their arguments by characterizing them as “a tactic” that was plotted “in reaction” to threats against conservative doctrines, and he accuses the scholars themselves of unscholarly “wish fullfilment (sic)”, and to cap it all off he infers that Schweitzer’s arguments have so stood the test of time that they are the only ones followed by entirely disinterested scholars:

Most of those who reacted to Weiss and Schweitzer took an angle still used by more conservative Christian scholars today – the idea that Jesus himself represented God’s intervention in the world and that all references to the “kingdom of God” are to him and his arrival. This “realised eschatology” is most closely associated with J.A.T. Robinson and C.H. Dodd and a form of it is still used by current conservatives like N.T. Wright. But Schweitzer laid out the arguments against this tactic back in 1910 and more modern attempts to prop up this idea do not have any more strength than they had a century ago. As many of the gospel texts cited and quoted above show, Jesus is consistently depicted as declaring the kingship of God as something that is “close” or “draws near” and is “coming”. As we have seen, it is only in the later texts that this gets replaced by the idea that it is “among you” or is embodied in the Redeemer Jesus. . . . .

But Jesus as an Jewish apocalyptic prophet does not represent any wish fullfilment (sic) by the scholars who hold this view. . . .

Now Tim O’Neill might be right to follow Schweitzer here, but I cannot know that he is. When scholars disagree on theological points that hinge on the correct interpretations of Greek words I personally feel uncomfortable taking a firm stand on either side. I think a case that rests on one particular translation of a disputed passage is not one to bet one’s house on.

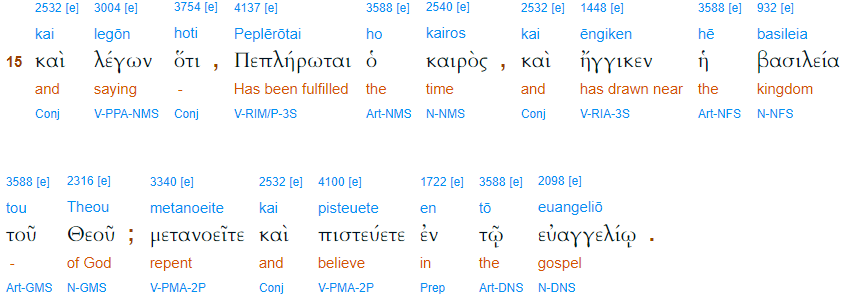

After reading the United Bible Society’s Translator’s Handbook on the Gospel of Mark by Robert G. Bratcher and Eugene A. Nida I am left feeling making a firm decision for one translation over the other is beyond my area of expertise. Here is Mark 1:15 in the Greek from biblehub:

I quote the Translator’s Handbook commentary on Mark 1:15 in full. I have highlighted certain passages with bold font PLUS underlining to draw attention to the possibility that Mark 1:15 can mean that the time is not future but now, and that God’s kingdom “has now come”. Alternative possibilities are presented.

1.15

Exegesis: hoti ‘that’ is recitative, introducing direct speech (cf. 1.37, 40, 2.12, etc.). Turner (Journal of Theological Studies 28.9–14, 1926–7) catalogues some 45 instances of this use of hoti ‘that’ in Mark.peplērōtai (14.49) ‘is fulfilled.’ The verb plēroō ‘fill up,’ ‘complete’ when used of time indicates that a period of time has reached its end (cf. Gen. 29.21). Moulton & Milligan show that this use of the word is not peculiar to Scriptures, quoting a papyrus: “the period of the lease has expired.” The verb is used only in the passive in the N.T. and early Christian literature. “The time has run its course and reached its end: the appointed hour has arrived.” The implied subject of plēroō is God: Jeremias (Parables. 12 et passim) has abundantly shown that the passive in the N.T. is often a “circumlocution…to indicate the divine activity.”

ho kairos (10.30, 11.13, 12.2, 13.33) ‘the time’: not simply chronological time, but opportune time, appointed time, “season” (Kennedy Sources. 153). Cf. ‘appointed time’ Eze. 7.12, Dan. 12.4, 9 (cf. Eph. 1.10). The word (as Arndt & Gingrich 4, point out) is one of the chief eschatological terms in the Bible: kairos is supremely God’s time.

kai ēggiken hē basileia tou theou : ‘and the kingdom of God has drawn near’ (or, ‘has arrived’).

eggizō (11.1, 14.42) ‘approach,’ ‘draw near.’ The force of the perfect has been the object of much debate. Dodd (Parables. 44). Lagrange, Black (Aramaic. 260–62) argue that the meaning is ‘has come’ or ‘has arrived’ (Manson). Kilpatrick (TBT 7.53, 1956) rightly observes that one’s conclusion “must be determined in part by other considerations” than purely grammatical ones. Black’s argument that the words ho kairos peplērōtai ‘the time is fulfilled’ are decisive for the meaning ‘has come’ is not lightly to be denied (for a forceful presentation of the meaning ‘has drawn nigh’ see R. H. Fuller The Mission and Achievement of Jesus, 20–49, and W. G. Kummel Promise and Fulfilment, 19–25).

hē basileia tou theou ‘the kingdom of God.’ Dalman (Words, 91–147) has conclusively demonstrated that the meaning of basileia is that of exercise of royal power. Arndt & Gingrich: “kingship, royal power, royal rule, especially the royal reign of God.”

metanoeite (6.12) ‘repent (you, pl.)’ (cf. v. 4).

pisteuete en tō euaggeliō ‘believe (you, pl.) in the gospel.’

pisteuō (5.36, 9.23, 24, 42, 11.23, 24, 31, 13.21, 15.32, 16.13, 14, 16, 17) ‘believe.’ Here only in the N.T. is the construction pisteuō en ‘believe in’ to be found (John 3.15 and Eph. 1.13 are not true parallels). Moulton (Prolegomena. 67 f.) at one time agreed with Deissmann that pisteuō is here used in an absolute sense, being correctly translated “believe in (the sphere of) the Gospel” (cf. Moule Idiom Book. 80 f.). Later, however (cf. Howard II, 464). Moulton changed his mind and accepted the construction as translation Greek, meaning simply, “believe the Gospel.” Gould comments: “The rendering ‘believe in the Gospel’ is a too literal translation of a Marcan Semitism.” Manson translates: “Believe the Good News.”

euaggelion (cf. v. 1) ‘gospel’: some (Taylor, Gould, Lagrange) hold that the meaning here is literally ‘the good news’ (cf. Weymouth: “this Good News”), while others maintain it has the technical Christian sense of “the Christian message.” In the light of v. 1 the latter is to be preferred.

Translation: In rendering and saying one must often separate it from the preceding verse and make it an independent verb expression ‘he said,’ with whatever appropriate connective (if any) may be employed.

Since time in this instance is a point of time (an opportunity or occasion), its equivalent in many languages is ‘day.’ One must avoid using a word which implies extent of time (which is an entirely different Greek term, see above).

Is fulfilled is admittedly a difficult expression, unless one translates the idea, rather than the word—this, of course, is fundamentally what one must always do. One can either say ‘the day has come’ or as in some languages ‘this is the day.’ In Shipibo there is an interesting idiom ‘the when-it-is (referring to any occasion) is already coming-up’—very appropriate equivalent of the Greek. In some languages, however, one cannot speak of ‘days coming’ but only of ‘people coming to the day,’ which is equally acceptable, if this is the normal way in which people describe the fulfillment of time.

If in verse 1.14 the Textus Receptus is adopted, it is possible to speak of the kingdom of God as ‘where God rules’; in this verse, however, we must speak of the kingdom of God in terms of time. Accordingly, in Huastec, even though in 1.14 kingdom is translated as ‘where God rules’ (the more usual form of the expression), in 1.15 it must be rendered as ‘now is when God is going to reign.’ The idea of immediate future implied in the expression is at hand is rendered in Zoque as ‘God is soon going to rule.’ In Pame the translation is ‘God is soon going to make himself the ruler.’ Another possibility is ‘God the ruler is here.’

For repent see 1.4.

A key word in any Scripture translation is believe. However, finding suitable equivalents (several are usually necessary depending upon the context) is admittedly very complex, for such expressions as believe a report, believe a person and believe in a person are frequently treated in other languages as quite different types of expressions. For discussions of some of the problems relating to the translation of believe and faith (these contain the same basic root in Greek), see TBT, 1.139, 161–62, 1950; 2.57, 107–8, 1951; 3.143, 1952; 4.51, 136, 167, 1953; 5.93, 1954; 6.39–41, 1955; BT, 230; GWIML, 21, 118–22, 125. Cf. Hooper Indian Word List , pp. 172–73.

Since belief or faith is so essentially an intimate psychological experience, it is not strange that so many terms denoting faith should be highly figurative and represent an almost unlimited range of emotional ‘centers’ and descriptions of relationships, e.g. ‘steadfast his heart’ (Chol), ‘to arrive on the inside’ (Trique), ‘to conform with the heart’ (Timorese), ‘to join the word to the body’ (Uduk), ‘to hear in the insides’ (Kabba-Laka), ‘to make the mind big for something’ (Putu), ‘to make the heart straight about’ (Mitla Zapotec), ‘to cause a word to enter the insides’ (Lacandon), ‘to leave one’s heart with’ (Kuripako), ‘to catch in the mind’ (Valiente), ‘that which one leans on’ (Vai), ‘to be strong on’ (Shipibo), ‘to have no doubts’ (San Blas), ‘to hear and take into the insides’ (Karré), ‘to accept’ (Bare’e).

Though these are the expressions used in a variety of languages to express faith, one must not conclude that they can be used automatically in all types of contexts. For example, though in Uduk to believe in God is generally translated as ‘to join God’s word to the body,’ in this context one must speak of ‘joining the joyful word to the body’ (‘joyful word’ is the gospel). In Valiente, however, it is possible to speak of ‘catching the word in the mind’ (if one is talking about believing a statement), but ‘catching God in the mind’ (if one is speaking of faith in God). In some instances one must use a kind of paratactic construction to indicate faith in a statement, e.g. ‘to declare, It is true.’ This type of inserted direct discourse may be rather awkward, but it is an effective equivalent in some languages.

One special problem should be noted, namely, the tendency for some languages to make no distinction between words for ‘believe’ and ‘obey.’ At first this may seem to be a clear case of deficiency in the language, but it can be a distinct gain in the task of evangelism, for it prevents people from saying that they believe the gospel when they have no intentions of obeying its implications.

O’Neill points to many other passages that he claims agree with or support his interpretation of Mark 1:15, that Jesus preached that the rule of God was going to come some day soon. I don’t think I really need to address each of those passages here because any thoughtful reader can surely see that the passages he cites do not, at least in most cases, declare that the kingdom of God is going to come “very soon” from now. Read them. Most of those passages say that the judgmental arrival of God could happen “any time” — either very soon or a long time from now. The message is to be ready at all times, not just for the immediate future. The instruction is by implication to persevere even for a long time but to be ready “now” just in case.

Some of the other verses referenced by O’Neill can suggest the “coming in a day not far away” but they could also be interpreted to accord with the sense of the kingdom being here now in the presence of Jesus. We have to beware of circular reasoning once we start calling on such passages to support our view of a disputed phrase.

Other passages O’Neill claims refer to a cataclysmic shaking of the earth and heavens, but anyone familiar with the Old Testament sources of the imagery knows that references to stars falling from shaken heavens are metaphors for the destruction of cities.

Overlooked by O’Neill but surely significant is the way the Gospel of Mark conflates elements of his apocalyptic prophecy of Mark 13 with the Passion narrative of Jesus. Why is “Mark” messing with readers’ minds like that?

Notice, too, a very specific prophecy involving the high priest in Mark 14:61-62:

Again the high priest asked him, “Are you the Messiah, the Son of the Blessed One?”

“I am,” said Jesus. “And you will see the Son of Man sitting at the right hand of the Mighty One and coming on the clouds of heaven.”

Stop and think a moment about that. The author of this gospel was writing some time after 70 CE so he surely knew that the high priest failed to live to see “the Son of Man sitting at the right hand of the Mighty One and coming on the clouds of heaven” — at least if we read Mark literally. So why did he record a prophecy of Jesus that he surely knew had failed? We are forced to ask how much of the Gospel of Mark is meant to be interpreted literally. Perhaps the following may help us come to an answer:

Mark 4:34

He did not say anything to them without using a parable.

Mark 8:14-21

14 The disciples had forgotten to bring bread, except for one loaf they had with them in the boat. 15 “Be careful,” Jesus warned them. “Watch out for the yeast of the Pharisees and that of Herod.”

16 They discussed this with one another and said, “It is because we have no bread.”

17 Aware of their discussion, Jesus asked them: “Why are you talking about having no bread? Do you still not see or understand? Are your hearts hardened? 18 Do you have eyes but fail to see, and ears but fail to hear? And don’t you remember? 19 When I broke the five loaves for the five thousand, how many basketfuls of pieces did you pick up?”

“Twelve,” they replied.

20 “And when I broke the seven loaves for the four thousand, how many basketfuls of pieces did you pick up?”

They answered, “Seven.”

21 He said to them, “Do you still not understand?”

There are many scenes in the Gospel of Mark that make no sense as history or biography but are perfectly intelligible if read as parables or metaphors. (R.G. Price’s book Deciphering the Gospels covers this theme as well.) A classic example is the need for four men carrying a paralytic to dig through the roof of a house to bypass the crowds preventing access to Jesus through the doorway, yet when the paralytic is healed he has no problem waltzing through the suddenly cleared doorway back to his home! Certainly we can imagine many extra details to make a sensible story out of it, but that’s the point: the story and many others like it don’t make sense as they are written. It is left up to “Matthew” and “Luke” to rework some of those scenes so they do make sense as realistic stories.

I am not prepared to bet my life on Mark 1:5 meaning either that the kingdom is “coming some day soon” or that the kingdom is “here now”. Or perhaps it even means both. The more familiar one becomes with the Gospel of Mark the more instances of such ambiguities one sees. One begins to wonder if the author was deliberately playing with ambiguities of meaning throughout his entire narrative.

A reliable historical reconstruction needs to rest on more secure sources than disputed interpretations of Greek terms or a disputed point of theology.

In the next and probably final post I want to make in response to O’Neill’s argument for a genuinely historical apocalyptic Jesus I will zero in on the most fundamental flaw in his method, one that is all too common among biblical scholars and that sets apart historians of the New Testament from other historians of ancient times.

Bratcher, Robert G., and Eugene A. Nida. 1993. A Handbook on the Gospel of Mark. New York: United Bible Societies.

If you enjoyed this post, please consider donating to Vridar. Thanks!

“(R.G. Price’s book Deconstructing Jesus covers this theme as well.)”

Not me. Deconstructing Jesus is Robert M. Price, haha the confusion sets in! 🙂

Anyway, another big issue is the Parable of Wicked Tenants. I think the Parable of the Wicked Tenants is clearly a parable against the Jews in favor of the Romans.

So how again is Jesus the Messiah that the Jews were hoping for? I mean, the Jesus of Mark is practically an anti-Messiah. The irony of Tim’s claim is that the Gospels offer horrible support for the idea that Jesus was worshiped by Jews because he was the Messiah, as the Gospels clearly depict Jesus being rejected by the Jews, which is the whole point of their theme, lol.

If Jesus was just a clear messiahic prophet, then why do the Gospels depict everyone hating him and all of his followers misunderstanding him?

the Jesus of Mark is practically an anti-Messiah.

Messiah~Christ, lol.

Ouch. Of course. Apologies.

I had to add just one more reply:

More problems for this thesis you’ve laid out. It’s very clear that the Jesus character of the Gospel of Mark is not intended to be a Jewish savior and isn’t someone who would ever be confused by Jews as a messiah.

Let’s look at the big picture we get of Jesus from GMark.

1) Jesus’ followers don’t understand him. They fail to comprehend any of his teachings, they fail to recognize him as the messiah, and ultimately they all abandon him. The Jews as a whole reject him and are fearful of him.

It is a gentile woman that first really understands him. It is a Roman solider that declares he is the son of God.

This is a very odd story about a man that somehow persuaded a bunch of Jews to worship him as the eternal son of God who would usher in a new perfect world with the overthrow of Roman rule!

2) The Parable of the Wicked Tenants is one of the clearest pieces of symbolism in the whole story. The Parable of the Wicked Tenants is a literary allusion to Isaiah 9, but it is clearly, both directly and as a literary allusion, an allegory against the Jewish people.

“Mark 12:

1 Then he began to speak to them in parables. ‘A man planted a vineyard, put a fence around it, dug a pit for the wine press, and built a watch-tower; then he leased it to tenants and went to another country. 2 When the season came, he sent a slave to the tenants to collect from them his share of the produce of the vineyard. 3 But they seized him, and beat him, and sent him away empty-handed. 4 And again he sent another slave to them; this one they beat over the head and insulted. 5 Then he sent another, and that one they killed. And so it was with many others; some they beat, and others they killed. 6 He had still one other, a beloved son. Finally he sent him to them, saying, “They will respect my son.” 7 But those tenants said to one another, “This is the heir; come, let us kill him, and the inheritance will be ours.” 8 So they seized him, killed him, and threw him out of the vineyard. 9 What then will the owner of the vineyard do? He will come and destroy the tenants and give the vineyard to others. 10 Have you not read this scripture:

“The stone that the builders rejected has become the cornerstone;

11 this was the Lord’s doing, and it is amazing in our eyes”?’

12 When they realized that he had told this parable against them, they wanted to arrest him, but they feared the crowd. So they left him and went away”

To quote myself from my book:

“The meaning of the parable is fairly basic and self-explanatory, though it is further explained via the literary allusion. The vineyard represents Israel or Jerusalem, and the man who planted it represents God. The tenants are the Jews, and the people that the man sends to collect from the tenants are supposed to represent various prophets. The “beloved son” whom the man eventually sends of course represents Jesus. The conclusion of the parable is that the “owner” will come to destroy the tenants and give the vineyard to others, of course meaning, in this context, that God will destroy the Jews and give their land to the Romans.

I highlight this parable for obvious reasons. The parable lays out the basic course of events that essentially explains the entire Gospel of Mark. The Jews kill Jesus; therefore, God destroys the Jews. This is the summary of the entire allegorical story. The subtext and deeper meaning behind it deal not with Jesus but with the perceived corruption of the Jewish people, who are believed by the authors of both Isaiah and the Gospel of Mark to have brought destruction upon themselves.”

How can you glean Jesus being a sought after champion for the Jews from the Gospels? There is really only one Gospel that can give this impression and that is the Gospel of Luke, which clearly is just a revision to the Markan narrative meant to re-cast Jesus as a more Jewish friendly figure. In Mark and John especially Jesus is clearly strongly against not just the Jewish leadership, but his own followers and the Jewish people as a whole.

Matthew is a bit more neutral and Luke turns Jesus against the Romans to put him on the side of the Jews.

But as I lay out in my book, the best explanation of GMark is that it is a story written by a follower of Paul. Paul’s message was against the law, against many aspects of Jewishness, he was against the pro-Jewish leaders of the Jesus movement (James, John and Peter). Paul told his followers that the law was overthrown (not a message that was welcome to Jews at all), that there were no differences between Jews and Gentiles, and Paul railed against Jews who tried to push Jewish practices on Gentiles.

These are ALL of that exact same characteristics we see in the Jesus of Mark.

But GMark and Paul also tells us why a real person like this would never have been even considered a leader or messiah among Jews: the Jews rejected Paul! Again, we see in GMark Jesus as Paul. The Jews reject Paul, the Jews reject Jews. The crucifixion of Jesus is the figurative crucifixion of Paul that Paul talked about so much in his letters. But any real Jesus in the likeness of GMark would have been rejected by the Jews for the exact same reasons that they rejected Paul, in that the Pauline message was anathema to Jews, which Paul himself admitted!

Does the gentile woman who “truly understands him” act or speak any differently from the way a few of the Jews (e.g. Bartimaeus; others healed completely) who are healed appear to understand and follow him?

Is Bartimaeus a Jew?

It says his name means son of Timaeus, and Timaeus is Greek, or at least so I think.

Is the Gerasene demoniac Jewish or gentile?

Anyway, the dialog with Syrophoenician woman I think is a bit different because it’s a real dialog where they have a conversion. He grants her please because of the wisdom of her reply. Also, it seems that the others who recognize Jesus do so because they are possessed by demons and its actually the demons that recognize Jesus as in the case of the Gerasene demoniac.

Bartimaeus was a blind man outside Jericho who recognized Jesus as a son of David and then willingly followed him on the way to Jerusalem. (I don’t think there was anything unusual about Judaeans having Greek or Latin names, especially Hellenized Jews and the name in this case suggests.)

Per Stephen L. Huebscher (21 August 2017). “Heavenly Worship in Second Temple Judaism, Early Christianity, and Gnostic Sects: Part 5”. Dr. Michael Heiser (blog).

One of these days, probably more like years, historians will come to know that there was no Jesus. I don’t have to explain that to anyone here. It would help people to learn the old ways of saying things. By that, I mean that the words used today lead us astray. Historians search in the wrong place because the words are not right. “The Kingdom of God is near” could never have been said. They are modern words. For one thing, John was not a god worshipper, would have never said “God”; he would have never said “Kingdom”, also modern. Yet there is a celestial time when change comes upon the earth and its people, the end of a cycle. The “King of Light” simply means the highest light. The indigenous Hawaiians talk of the King Tides. This means the highest tides. Unfortunately, the word “King” translates very badly, and becomes sexist in the long run. Kings demonstrate power and control over their subjects, period. King is no longer an adjective when talking about highest light, tide, wisdom or anything else. John is no longer known. Nothing is known of him. He taught people how to use the highest light. It simply means, the kind of light that works and comes from following the magnetic fields of the earth which come from the sun, and which originate in the mind. Amidst all of their corruption, the Catholics held onto one word, “will”, as this kind of light really has to do with consciousness and willing something into existence.

Please allow me to show off some of my expertise here. My pertinent specialties include lack of detailed knowledge of the ancient Mediterranean world and ability to ask stupid questions.

Were there not kings in the ancient world, and would not there therefore have been words nearly equivalent in meaning to ‘kingdom’ that could have been used metaphorically? I wonder whether the question almost answers itself.

A trickier question, and one that has often bothered me, is the degree to which there were words in the region at the time that were nearly equivalent to ‘God’. We know that English translators have done a bit of sleight of pen in translating the words for ‘Yahweh’ and ‘Elohim’ as LORD and God, but was there a word meaning approximately ‘God’ in the region at the time? For example in Persia? What about in Greek?–when I read a translation of an ancient Greek play and see ‘God’ was there a word meaning something like our ‘God’? In Rome and in Latin?

[I do have some professional knowledge about the magnetic fields of the earth. They do not at all come from the sun though they are ever so slightly modulated by solar phenomena. Whether they and other things originate in the mind is up for philosophical or religious debate or speculation.]

Or to put my stupid question about ‘God’ another way, perhaps the Zoroastrians were monotheistic (I don’t know much about them), but otherwise was there anything in the ancient Mediterranean world truly equivalent to our word ‘God’? I appreciate that with most Christians there is ambiguity about a single entity what with the Trinity, but is it possible that even Jews were as much polytheistic as monotheistic what with all the angels/demons/archons/whatevers manipulating earth and the various heavens? Was what from that time and region gets translated as ‘God’ include far more than gets used by that term nowadays, and was it, as Christine perhaps implies, much less of A Thing back then?

A naive (and perhaps unanswerable?) question.

In Latin, the standard term for “[a/the] god” was (in the nominative case) deus. In Greek, if I understand right, the standard term for “[a] god” was (in the nominative case) theos (θεός).

Yes, as Buddhist says, there was a term for “god”. Sometimes it would be used to express the idea of one God above and over all, and if we didn’t know better we might even think the authors were monotheists and speaking of “our God”.

The people who produced the Jewish scriptures appear to have been re-working the myths of different deities of people around them and changed their gods into human heroes or angels. This may have been done under the influence of Plato’s complaint that many of those tales of gods were either silly, demeaning or immoral. See posts here with reference to Russell Gmirkin‘s books and Philippe Wajdenbaum.

Van Kooten, George H. (2014) [now bolded]. “The Divine Father of the Universe From the Presocratics To Celsus: the Graeco-roman Background To the “father of All” in Paul’s Letter to the Ephesians”. In Felix Albrecht; Reinhard Feldmeier. The Divine Father: Religious and Philosophical Concepts of Divine Parenthood in Antiquity. BRILL. p. 294. ISBN 978-90-04-26477-9.

Not forgetting our earlier posts on this topic:

How Polytheism morphed into Monotheism: first steps

How Polytheism morphed into Monotheism: philosophical moves, 1

How Polytheism morphed into Monotheism: philosophical moves, 2

Thank you, all of you, for your comments. I have reading to do.

Another thing I have wondered — I am scared I will provoke people to waste time responding, but perhaps I can perhaps provoke people to think — is the extent to which there might have been a spectrum in the ancient Med world from those who took the deities literally to those who didn’t (total skeptics who pretended to believe, those who believed but in a consciously figurative sense, those who saw the deities figurative manifestations of some life force etc).

[[In thinking over the matter I noted to myself that in some versions of Christianity where there is God there not only is the Trinity but there are saints who are treated almost as if deities, esp the Mary of the birth story, and perhaps in some localities where Christianity was forced on locals by conquest, such that certain saints tended to get merged a bit with prior deities.]]

• What time period did you have in mind?

The difference between “Middle Platonism” and “Platonism” is crucial, they are not the same.

See” Arthur F. Holmes. “A History of Philosophy | 18 Middle and Neo-Platonism”. YouTube. wheatoncollege. 14 April 2015.

Per Stephen L. Huebscher (28 July 2017). “Heavenly Worship in Second Temple Judaism, Early Christianity, and Gnostic Sects: Part 2”. Dr. Michael Heiser (blog).

Cf. Attridge, Harold W. (1989). The Epistle to the Hebrews: A Commentary on the Epistle to the Hebrews. Minneapolis:Fortress Press. ISBN 978-0-8006-6021-5.

My latest reply to him:

Tim, what you’re failing to grasp is that the Jesus cult clearly started out as a Jewish cult. The Jesus of this cult had to be a figure who appealed to Jews. The Jesus of the Gospels is already a fictional character meant to appeal to Gentiles. This figure can’t possibly have anything in common with the Jesus that initiated the worship of the cult.

We know exactly what happened because we have an account of it in Paul’s letters. The Jesus being worshiped by the founders of the cult was a Jewish savior figure, like Melchizedek, like the predicted messiahs in the line of David or Aaron. Then Paul came along and started espousing his Gentile version of Jesus. Paul argued with the Jewish leaders, told people not to follow them, and tried to convince his followers that he actually knew more about Jesus than they did.

This Gentile-friendly-Jesus of Paul is the Jesus we are presented with in the Gospels.

Now, in reply to my question about why don’t the early epistles talk about Jesus the man, you say, “Why does 1Clement and 2Clement make almost no mention of him as a man at all? Theology. ”

Really, theology? But let’s look. The Epistle of James is a very Jewish letter, that has about a dozen places where we would expect the author to talk about Jesus, yet he never does.

Example #1:

“James 1:2 Consider it pure joy, my brothers whenever you face trials of many kinds, 3 because you know that the testing of your faith produces perseverance.”

Right out of the gate. Why no discussion of Jesus’ trials and tribulations? Why not use Jesus as the example. Surely it would be fitting. > Whenever you face trials, remember Jesus and all that he went through, yadda, yadda…

“James 2:2 My brothers, do you with your acts of favoritism really believe in our glorious Lord Jesus Christ?”

Wow, perfect place to talk about how the Jewish leadership didn’t believe in Jesus and thus killed him. But no, instead we get a discussion about how you shouldn’t shun the poor. Why not address the fact that many people failed to recognize Jesus as the messiah here? What about all the other non-believers who scoffed as Jesus? No mention of any of that.

“James 2:21 Was not our ancestor Abraham justified by works when he offered his son Isaac on the altar? 22 You see that faith was active along with his works, and faith was brought to completion by the works. 23 Thus the scripture was fulfilled that says, “Abraham believed God, and it was reckoned to him as righteousness,” and he was called the friend of God. 24 You see that a person is justified by works and not by faith alone.”

Wow, now we are talking about the importance of works. What better example to give than the works of Jesus himself! Surely the author will point the example that Jesus set for us to follow! Nope, the author points out the deeds of Abraham and then the prostitute Rahab. If you are looking for someone to emulate, looks to Abraham and prostitutes. Our Lord Jesus? He proved no examples.

“James 5:15 The prayer of faith will save the sick, and the Lord will raise them up; and anyone who has committed sins will be forgiven. 16 Therefore confess your sins to one another, and pray for one another, so that you may be healed. The prayer of the righteous is powerful and effective. 17 Elijah was a human being like us, and he prayed fervently that it might not rain, and for three years and six months it did not rain on the earth. 18 Then he prayed again, and the heaven gave rain and the earth yielded its harvest.”

Ahh… here we see talk about the Lord (Jesus) raising the sick, but this is achieved through prayer! And how does the author convince his readers of the power of this prayer? Through the example of Elijah! This would be the perfect place to pass on a story about the real human Jesus healing people with the power of prayer, but no…

And we are assured that “humans like us” can wield the power of prayer. Not with Jesus as the example, but with stories of Elijah from the ancient scriptures.

And to top it all off, we have the ultimate example:

“James 5:10 As an example of suffering and patience, brothers, take the prophets who spoke in the name of the Lord. 11 Indeed we call blessed those who showed endurance. You have heard of the endurance of Job, and you have seen the purpose of the Lord, how the Lord is compassionate and merciful”

Yes, brothers, when it comes to enduring suffering, look to the prophets of old as your example, never mind our “glorious Lord Jesus” who was tortuously crucified to death in a public spectacle!

How does someone who knew of Jesus as a person who was going around shouting apocalyptic teachings, who was rejected by most Jews, and who was killed by the Jewish leadership write this letter?

They don’t. This letter can only be accounted for by disregarding it or coming up with weak rationalizations. Certainly the clearest interpretation of this letter is that it was written by a Jew who only knew of Jesus as a heavenly savior that had been revealed by prophets, not as a real person who was himself a prophet. There is no attempt in this letter to assuage people’s doubt or fears about Jesus. There is no need to convince them that, despite the fact he was killed by the leaders, he was relay a good guy. There is nothing like that. Nor does Paul engage in that either. Why didn’t Paul need to address widespread fears about Jesus being a false prophet? Because there was no Jesus who was ever perceived as a false prophet, that’s why. But the Jesus of the Gospels, the only Jesus ever presented as a prophet, is someone that Paul and James would surely have to address. The idea that such a Jesus man could just be ignored by the early proponents of the cult is ludicrous.

If the Jesus cult began with the Jesus of the Gospels the early epistles would have to have been constantly addressing that person and dealing with the existing fears and doubts that existed among the people about him. Yet the rabble-rousing prophet who spoke against the leadership and the temple is totally ignored, as is nothing he did had ever happened. Well, that’s because it didn’t.

Are you saying that “the Jesus [of Nazareth] cult clearly started out as a Jewish cult” because of the canonical Epistle of James?

My understanding is the Epistle of James is hardly attested until the fourth century and, even then, not fully attested until Cyril of Jerusalem does so in the early fourth century (and that is the case with other non-Pauline epistles such as 2 John, 3 John, and even the Epistle of Jude (which seems to have been known to Clement of Alexandria, and may have been known by Tertullian).

“My understanding is the Epistle of James is hardly attested until the fourth century”

That may be, but its also widely acknowledged as an early work by biblical scholars as well.

G.A. Wells. “Earliest Christianity”. infidels.org.

Tim, what you’re failing to grasp is that the Jesus cult clearly started out as a Jewish cult. The Jesus of this cult had to be a figure who appealed to Jews.

Hoshana! Hoshana! Hoshana! 🙂