A first century Greek named Strabo documented an account he heard or read on the founding of a colony at present day Marseilles, southern France. The founders were from the Greek city-state of Phocaea, present day Foça on the Turkish coast. The date of the founding was around 600 BCE.

In 2005 Vetus Testamentum published an article by Professor Nadav Na’aman of Tel Aviv University that drew attention to a unique combination of details in both the Greek foundation story of Marseilles and the story in the Book of Judges about the foundation of the city Dan.

You know the story in Judges 17-18 but here are the main points to refresh your memory.

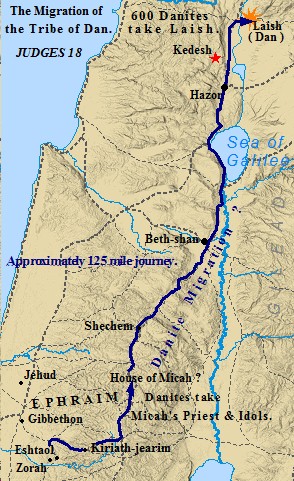

Many of the tribe of Dan were looking for a new place to settle. They selected five men to go out and spy in other places and report back on the best place to migrate to.

Meanwhile in the region of Ephraim a certain Micah established himself with images of gods and made one of his sons a priest. But soon afterwards a Levite looking for a new home came by and Micah promptly offered him remuneration too good to refuse to be his priest. Much better to have a bone fide priest — that is, a Levite.

Back to the story of the Danites. The five spies came upon Micah’s house and asked the Levite priest for a sign or message from God about the chances their efforts in finding a new land would be successful. The Levite was able to inform them that God would certainly favour their mission. And he did.

So the five returned to their fellow Danites and began to lead them to their new homeland. On their journey they once again passed Micah’s house. This time they invited themselves in and took the images of his gods. When the Levitical priest challenged them he was intimidated and bribed into joining them and becoming the priest of whole tribe. The Danites travelled the rest of the journey with the gods and the priest.

When Micah also tried to challenge them he was bluntly cowered into accepting the situation and loss of his images and priest.

The story ends happily for the Danites who build their new city, Dan. And the first thing we learn that they did was to set up the images in a proper place and institute a new priesthood.

That’s the story you will recall.

Now the many details are quite different from the old story that Strabo documents. But the similarity in structure and the unique combination of details are noteworthy. You can read Strabo’s narrative in the fourth paragraph here.

Here is the outline.

The Phocaeans made a decision to leave their city in Asia Minor (Turkey). On their journey they received an oracle in a dream advising them to take on their journey a guide from the goddess Artemis of Ephesus.

They weren’t quite sure of the details of how they were to find that guide but they did berth at Ephesus and made inquiries at Artemis’s temple. Among the prominent women devotees at the temple was Aristarcha. The goddess appeared to her in a dream, commanding her to go with the colonists and to take with her a sacred image of the goddess.

The Phocaeans finally settled at Massilia (now known as Marseilles) and built a temple to Artemis there, installed the image they had brought with them from Ephesus, and made Aristarcha their high priestess.

“Unmistakable Similarities”

Nadav Na’aman itemizes four “unmistakable similarities between the two stories”:

- Both describe a migration from an ancestral place and the founding of a new city.

- The settlers obtain “oracular confirmation” for their respective colonies or cities.

- In each story the colonists stop by a place on their route and obtain from there both a priest/priestess and a cult image.

- At their new destination they both set up a temple where they place the sacred image and establish a priest/priestess to serve in it.

The most prominent common features of the two stories are obtaining the cult image and the priest/priestess in a place located on the way, and their establishment in the new settlement. The combination of these features in a foundation story is unique and raises the question of the relationship between the two stories. Is the similarity purely accidental; or is it possible that one text borrowed some outline from the other?

(p. 59)

John Van Seters, Nadav Na’aman informs us, suggested Phoenicia as a likely meeting ground between Greek and Asiatic ideas in order to explain various similarities in the historiographical literature of the Greeks and Hebrews. I came across Na’aman’s article in the course of following up citations in Russell Gmirkin’s Plato and the Creation of the Hebrew Bible. Gmirkin, as many of us know, proposes that the Great Library of Alexandria in Egypt is a better candidate for explaining West-East similarities such as are found in the colonizing travels of the Greek Phocaeans and biblical Danites.

Na’aman’s article covers more territory than I have addressed. What I have left out here are his discussion of the polemical function of the Danite story: it undermines the validity of Jeroboam’s efforts to establish a new cult in the northern kingdom of Israel after its split from the southern kingdom of Judah. I have also not covered his arguments for dating the narrative in the Book of Judges to the fifth or fourth century BCE.

If you enjoyed this post, please consider donating to Vridar. Thanks!

What strikes me when I read Biblical stories is that the structure of the stories are very similar to the structure of the Athenian New Comedy.

The structure goes like this, the hero starts as an accepted member of the society and by the events of the first part of the stories he reaches a low point, the last part are the events that brings back the hero to the first point and he lives happily and rightfully.

I do not believe that this is a coincidence.

Menander was a pupil of Demetrius of Phalerum, and Demetrius was invited by Ptolemy I (Soter) in Egypt.

Also New Comedy was used as a political propaganda by Demetrius.

Is that structure not an outline of most stories anywhere? (1) Status quo — (2) fall or crisis — (3) resolution and restoration.

OK, but there is no evidence for a Unified Kingdom, nor could any Israelite King ruling in the 10th century BCE have installed a shrine in Dan (which did not exist yet). If any Israelite king built such shrines (or temples) it would have been Jeroboam II in the 8th century BCE.

In any case, why would an author, whether writing in the Persian era or the Hellenic era need to undermine the efforts of either Jeroboam centuries after such temples were no longer in use, and the city of Dan well outside any jurisdiction of Yahweh worshippers? Isn’t it enough to follow the narrative in Kings that makes Jeroboam I (to whom the establishment of the temples is attributed) the source of ‘Original Sin’ as it were of the Northern Kingdom?

History is always about the present, not the past, as they say. If so, then the stories of Jeroboam and the wayward Danites functioned to cast aspersions upon the inhabitants of that region, namely “the Samaritans”, at the time the stories were written. The author, it might be said, was attempting to delegitimize the claims of Samaritans known to his readers in his own day.

So the Samaritans were bad guys for causing, one way or another, illegitimate forms of worship in that distant city of Dan, a city long lost from the Yahweh-sphere, but still remembered as the northern border city of Israel?

It seems that at first the mission of the Danites is favored by God, but eventually they are exiled (well, like everyone else, but the narrative makes a point of mentioning that their success was temporary). So I suppose the message is that current success is no evidence that God is happy with you and won’t turn the tables on you, or possibly your distant offspring.

Interesting that the story ends with a line that could be read as identifying the Levite priest as the grandson of Moses (the Massoretic text looks like the name ‘משה’ (Moses) was converted in to ‘מנשה’ (Manasseh). Was this related to conflicts about the legitimacy of certain priestly lines?

I expect to be posting more that will address some of your questions, and at least mention further books and articles as I do so.