A few months ago I posted about Michael Zolondek’s claims that historical Jesus scholarship uses the same historical methods as those used by other historians. Michael himself responded and I assured him and others that I would return to his book and compare his claims about his methods with the actual processes found in the book. I am finally getting around to returning to that promise. But first I need to refresh my memory on a few things and catch up with certain details. So those further posts I promised are still a few weeks away.

A few months ago I posted about Michael Zolondek’s claims that historical Jesus scholarship uses the same historical methods as those used by other historians. Michael himself responded and I assured him and others that I would return to his book and compare his claims about his methods with the actual processes found in the book. I am finally getting around to returning to that promise. But first I need to refresh my memory on a few things and catch up with certain details. So those further posts I promised are still a few weeks away.

Till then, however, I can say that I have caught up with one important volume Michael cites (p. xiv) as one of a few “useful discussions by historical Jesus scholars on ‘doing history’:

Meyer, Ben F. 2002. The Aims of Jesus: Reprint edition. San Jose, Calif.: Wipf & Stock.

The book was originally published in 1977 and an introduction in the reprint edition by N.T. Wright indicates that it has been very influential among the “less liberal” historical Jesus scholars.

The first of the two parts of Meyer’s book is about hermeneutics and historical methods. What I was looking for in particular was Meyer’s explanation for how biblical or historical Jesus scholars decide what is historical bedrock in the gospels. There is discussion about various criteria and inference and such. That word “inference”, distinct from “proof” or “fact”, reminded me of an objection PZ Myers’ raised in his discussion with Eddie Marcus. It was encouraging to see Meyers acknowledge the place of inference and its meaning in his discussion.

But then I came to a passage that echoed everything I have been come to see in how historical Jesus scholars work, but here it was stated in black and white.

Control of the data requires insight into how the gospel literature refers to the past of Jesus and this must be brought to bear on a mass of detail, repeatedly answering the question, ‘Is this a potential datum on Jesus?’

(Meyer, p. 81, my bolded emphasis)

Did you see it? The historical Jesus historian is required to have insight into how the gospels refer to the past of Jesus. The gospels are assumed to speak about the past of Jesus without question. Why? Presumably because they are a past tense narrative (notwithstanding Mark’s gospel regularly using the present tense). Presumably because they look like historical accounts (notwithstanding their significant departures from other historical accounts of the era). But let’s leave aside the “presumablies” and see what Meyer himself says. At the end of the chapter he spells it out:

Finally, the motives, values, uses, and ulterior purposes of history, be it ever so critical, are themselves metacritical presuppositions. They are not controlled by method but arise from the historian’s intellectual and moral being, and in the end they account more fundamentally and adequately than anything else for the kind of history he produces. For a history of Jesus what counts is especially the stance toward religion and faith.

(Meyer, p. 94, my bolding)

To me, that sounds like Ben Meyer is saying that a Christian historian will necessarily approach the gospels as if they are “obviously” reports of the “past of Jesus” and the task of the historian is to work out how much those gospel accounts have added to or coloured the actual historical past of Jesus.

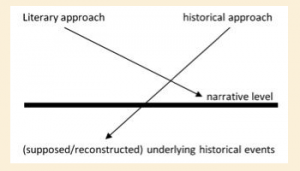

The possibility that the gospel accounts are not history or not even based on historical events at all never so much as approaches Ben Meyer’s mental horizon. The model that James McGrath used to describe a historical reading of the gospels is affirmed. The gospels are not read as literature but are read as gateways to imagining what happened independently of the narrative.

The assumption that the gospels are some sort of biographies or historical works is a presupposed “fact”. All the historical method discussion, all the discussion about how to determine a historical probable Jesus, is premised on the gospels being reports that are written in such a way that the researcher can validly “see through” their narrative and language and identify some image of historical persons and events. The narrative is assumed to be based on reports or memories of historical persons and events.

When I read the works of classicists and ancient historians I see the same approach to historical narratives only when that approach has been justified by identifications of authorship and provenance, and by independent contemporary verification and/or by identification of relatively reliable historical sources for that narrative. We see none of those things in the case of the gospels.

If you enjoyed this post, please consider donating to Vridar. Thanks!

It appears to be rather a mystical approach, poring over scriptures to obtain your own personal vision of the True Jesus.

Kind of how Paul did it.

With a little help from an epileptic seizure.

or via a dream-vision

I think you hit on the bedrock problem, Neil, those who believe in a real substantial Jesus (a Jesus who did and said at least a significant number of the non-supernatural things described in the gospels) believe that all history is subjective and therefore they a doing history just like everybody else.

One can phrase this attitude as something like this: the historical is always debatable and thus dependent on the historian’s subjective feeling for what is historical.

This is true to a degree, but ignores the tremendous differences in subjective observation. If I say that Achilles did not exist, I only have to explain that Homer invented him to embody the negative traits of a brutish Greek Soldier. Other poets took their cue from him. If I want to say that Alexander the Great did not exist, I have to explain why Arrian, Plutarch, Diodorus, Curtius and Justin, all men who certainly thought they were writing history, believed so strongly in his existence. The first century Jesus character only fits as a literary creation in first century history, not as a literal person. You have to eliminate objective history and make it subjective to make the subjective Jesus objective and real.

It is a trick and not a nice one.

“Control of the data requires insight into how the gospel literature refers to the past of Jesus”

Insight. That’s gotta be as reliable as gut instinct.

Well, I hope my book puts this entire argument to rest.

The response will be like Ehrman ap. Ben Witherington (5 June 2012). “Bart Ehrman’s on Did Jesus Exist?“. The Bible and Culture.

Yeah, but I put forward a lot more direct evidence. There is a difference between talking about similarities, and showing direct textual dependency.

RG Price, I have read your book and I am galvanized by the his sound scholarship.

Only a thing I found missing and I would like an answer by you: what do you think about the fact that the original readers of Mark, according to Irenaeus, were separationist Christians, in addition to the fact that effectively a separationist reading of the Markan christology is strongly plausible, even probable?

How does the separationism fit in the your view of Mark as fictional political propaganda post-70 CE etc?

Thanks in advance for any answer.

I don’t view GMark as either Separatist or Adoptionist. I don’t think the author was trying to write theology at all. I think pretty much every Christian reader of the Gospel of Mark misunderstood the story completely. I don’t think the intention of the work was to try and convince anyone of a particular view of Jesus. I don’t view the story as being about Jesus at all, I view it as being about the Jews and the leaders of the Jesus cult. I think the writer of the story knew full well that Jesus wasn’t real and had no intention of convincing anyone that he was. I think the purpose of the story was to show that the Jews and the Jesus apostles didn’t understand God and, and that their ways and beliefs are what led to the war, because they were misguided, ignorant fools.

I think that was the author’s intent. I don’t think the author was trying to establish any doctrines or establish any views of Jesus at all. Jesus is just a foil.

Reading the above, and the following on Biblical Criticism & History Forum:

“I think the writer of GMark viewed the Jesus cult as a failure, evidenced by the outcome of the First Jewish-Roman War. The story basically mocks the Jesus movement and blames them for the war, along with other elements of Jewish society. That this story became the basis of a new religion worshiping Jesus is a supreme irony.”

I think you are off in the realms of the very improbable here. Granted, you haven’t tippled over into downright loony; but you are getting there. I’d leave this out if I were you, you are only going to poison the well for the rest of what looks like a very decent hypothesis.

Not sure why. The author obviously knew that he was making up a fictitious story. The author knew that he was basing his character on Paul.

The disciples, especially, Peter, James and John, are portrayed as fools, idiots, and betrayers throughout the story. Peter is essentially the reason that Jesus was arrested. He wasn’t keeping watch like he was supposed to, and then he denied Jesus. Peter is never redeemed in the story.

The story presents the failure to recognize Jesus as the savior of Israel as the cause of the war. The disciples failed to stop his execution, and the Jews themselves killed him. It’s all their fault. They failed to understand him, they failed to know his message, they failed to recognize him, they failed to save him. They just utterly failed.

And as a result, the temple was destroyed. It’s pretty straight forward IMO.

Neil wrote:

Dr. McGrath certainly seems to think we know a great deal about Jesus. He writes:

Dr. McGrath’s Jesus isn’t only known to have lived, but is an ethical superhero! I’m not familiar with Dr. McGrath’s methodology here, but I am reminded of Crossan’s book “The Power of Parable” where we learn that the most socially responsible parables (the challenge parables) are also the ones that happen to go back to the historical Jesus.

Jesus was a super-nice guy, so he must have said it!

Meta-metaphors of course, only the progressived revealed to can see the truth.

The critical error Jesus scholars make — one no good historian would — is a misplacement of the chronological start for the inquiry itself. They begin, of course, at the AD 30’s marker implied by the text, then proceed forth.

The correct starting point is the mid-2nd Century appearance of the first gospel, and the imperative questions ought to be: who produced it; what was their purpose; what was the Sizt-im-Leben? And then to work backwards, not forwards, to search for any trail.

For the most crippling element to the historicity of GMark is its lack of provenance. Compare, if you will, to the ‘discoveries’ of the Hitler and Jack The Ripper diaries. Before engaging in revisions of the consensus on these two figures, historians first sought to authenticate the diaries, while the suspicious lack of provenance raised concern.

Just as the flimsy explanations for those diaries’ provenance — ‘hidden in the Soviet Zone all these years’ or ‘stashed in someone’s attic all these years’ — did not fly, neither should ‘four decades of [imagined] oral tradition.’ The shoddy standards embraced by biblical scholars would, if allowed in general historical research, have lead to the full acceptance of the Hitler and Jack The Ripper diaries as authentic, and sparked a vibrant publishing industry based thereon.

Yes, the lack of provenance is a key issue that many people ignore.

I agree the starting point is the first appearance of commentary and other information which is, as you say, in the 2nd century.

There has been a lot of interest in Marcion in the last few years and, of course, he seems to be the first record of some of the Pauline epistles and aspects of Luke. Some scholars think he wrote or used a proto-Luke, and some think most if not all the synoptic gospels as we know them came after Marcion. Robert M Price think some or many of the Pauline texts originated via Marcion or his community, too. Justine Martyr did not seem to have known the Paulines, and he seemed to have scant knowledge of the synoptic gospels; and no or virtually no knowledge of the gospel of John.

Jörg Rüpke in his recent book, Pantheon: A New History of Roman Religion, seemingly followng Markus Vinzent and Matthias Klinghardt, says Marcion started it all with texts without communities yet established – Rüpke says there was great desire for new theological and philosophical texts in the mid 2nd century, and people lapped up the popular ones (he said ‘Shepherd of Hermas’ was very popular).

• Nobbs opines that New Testament Scholars may lack objectivity per the reading of a particular text.

Nobbs, Alanna (2017). “The Interaction between Ancient Historians and New Testament Scholars: A Critical Appraisal”. In Harding, Mark; Nobbs, Alanna. Into All the World: Emergent Christianity in Its Jewish and Greco-Roman Context. Wm. B. Eerdmans Publishing. pp. 1–5. ISBN 978-0-8028-7515-0.

• In contrast there have been instances of “commendable candour”.

Wells, G. A. (1999). The Jesus Myth. pp. 293f, n. 8:

Before you get back to commenting on my book please be sure to understand it. You again state that I argue historical Jesus scholars use the same historical methods as ancient historians generally. My claim is actually that historical Jesus scholars often do history differently than ancient historians generally. Quite an important point of clarification.

If you read my original post again you will be reminded that the point you are making here, suggesting I am unaware of it, is actually the point that led me into the discussion in the first place and that I quoted. To repeat that quotation, with the original emphasis of mine:

I think much of what you say you are doing in your published thesis is all very fine and good. What I will be addressing is that there is a gap between those assertions and the method you actually use in your argument. I think your claims often epitomize the gap between biblical scholarship on Christian origins and normative methods of historical inquiry in other fields. The quotes and references to nonbiblical historians seem to me to be cherrypicked without a serious knowledge of the context and practices to which they are actually referring. This is not just about you — it’s about a problem I encounter repeatedly among biblical scholars. Not all biblical scholars by any means, but many. Though let me be clear: I am not “attacking biblical scholars” themselves, but what I see as frequent resort to invalid methods. Otherwise I have learned enormous amounts from them and respect very much of the work many of them do.

Well that’s what I’m saying sounds quite different from what you wrote in this post. But I would again remind you that I am NOT saying that NT scholars work by far stricter standards than ancient historians in other fields. I never make that claim.

I know you don’t make that claim and it is surely clear that I do not say you do. Surely I cannot be clearer that I am comparing your claims with what I see you are actually doing and I am offering my own analysis of what you are doing compared with what you say you are doing. Are any facts of what I have said in the original post actually wrong?

But if you believe I have misrepresented you in this and in my earlier posts then can you explain the quotations I took from your work and set out in that original post:

On page 92:

Then again on page 96:

And on pages 98-99:

*

MZ redefines “criteria of authenticity” as “data”. Do we see in this redefinition of criteria as data the influence of Larry Hurtado himself. I learned some years back that Hurtado has an “idiosyncratic” view of the nature of data as raw material in historical research. See Who’s the scholarly scoundrel? for links and discussion relating to Hurtado’s confusion over the meaning of historical data.

**

MZ does add that he had apparently informal discussions with classicist and ancient historian Margaret Williams to learn that biblical scholars used the same methods as “other historians”. It turns out, however, that Margaret Williams belongs to the university’s School of Divinity and not to its School of History, Classics and Archaeology. Williams is also part of the Centre for the Study of Christian Origins so one has to question her ideological neutrality in any discussion that challenges the methods employed by her closest peers.

Okay, I feel like you are gas-lighting at this point. You just stated, “I know you don’t make that claim and it is surely clear that I do not say you do.”

Yet, your exact quote from the earlier post is: “It turns out that what MZ means here is that Jesus scholars “often times” are working by far stricter standards than anything followed by “ancient historians normally”, and that if only more Jesus scholars would lower their standards to be consistent with those found in Classics and Ancient History departments at universities they would, lo and behold, find their job much easier and be able to reconstruct and prove all sorts of things about Jesus.”

You clearly state I argued that Jesus scholars work by far stricter standards than ancient historians generally. I do not argue that.

As far as the quotes you list from me, I’m not sure what point you are trying to make. In those quotes I am engaging with Jesus scholars and the recent discussions over criteria of authenticity, abandoning them, and finding entirely new methodologies. My point in those quotes is that both those who utilize the criteria in the form-critical model and those arguing they have little-to-no value are both wrong. My point is that the criteria initially were attempts to adopt “tools” from ancient historical methodology and that if utilized as ancient historians more broadly utilize these “tools,” it’d be better.

Final quick note, Williams is a highly respected classicist.

I’m sorry but I fear you are misreading and unconsciously twisting my words. You write:

Yet you just quoted me saying something different. I was saying how I interpreted the meaning of your claims and argument, and that when one read your subsequent claims it was evident that you “meant” something you did not explicitly claim — or perhaps even recognize in your own argument.

The point of the quotations I set out was exactly the one I made in the original post to introduce those quotations from your dissertation:

Surely you are not suggesting that Williams is without biases and her opinion is beyond questioning.

There is not even a suggestion in my work that NT scholars work by stricter standards. My argument nowhere approaches that. So to say I meant it is entirely erroneous on your part, and I’m here yet again directly telling you that this is not my argument and so you no longer need to say that it is what I “meant” or appeared to argue. Not sure what more is needed. I assume we can agree that I don’t argue that now?

Again, you are simply misunderstanding. My argument is not about historical Jesus scholars generally, nor is it about them using the same methods as ancient historians more broadly. It as an argument about the criteria, how they should be conceptualized, and their value. My point was that we should move away from the form-critical conception of them and get closer to ancient historical methodology, which, yes, uses things like multiple independent sources, ancient authors’ biases in work and things that would appear to contradict them, and historical plausibility.

I am not saying she is without biases. You are not. I am not. No one is without them. I am saying she is widely respected among various fields of scholarship. I am saying you launched an ad hominem against her without ever having spoken to her (I’m presuming you haven’t). I don’t think she does any particular work in Jesus studies, and I believe only secondarily in NT studies. I am not even sure if NT studies is a focus of hers. I don’t know her religious affiliation. To throw doubt on her without knowing anything about her is unprofessional.

Williams can be a highly respected classicist, but if she be a Christian and a member of a Christian School of Divinity, one would be wise to question whether her Christian beliefs create biases as she works in a Christian environment.

I am a Buddhist, as my user name reveals, and do not want to defame the Three Jewels even unto tolerating Jonang Buddhists – yet you would not want to ask me, I hope, about whether I can criticize Buddhism? Why? Because I fear that defaming the Three Jewels can send me to a Hell Realm for some time. In the same way, Christian scholars of Christianity may be reluctant to fully probe their faith’s texts lest they lead themselves to apostasy, which, in the main Christian position, will damn them to an eternity in a Hell Realm.

I am in no way anything more than an amateur reader about issues related to the Bible – yet such led to my apostasy – but approaching the Bible from a Buddhist perspective, I am willing to consider any portion of it to be false if arguments can be made against the portion. Yes, hyper-skepticism in some people’s minds, but once one has recognized, through considering Buddhist arguments, that it is impossible for there to be a Supreme Creator God, any narrative claiming to be about a Supreme Creator God becomes suspect. Supreme Creator Gods not existing, what other portions of a narrative about a Supreme Creator God are not true? Yet the Christian lacks this check, and indeed believes that a Supreme Creator God has the properties ascribed to YHVH/Jesus in the Bible.

See my last paragraph in the above post.

Neil, when you say on the first line of this post –

– it comes across that you are saying “Michael Zolondek claims that historical Jesus scholarship uses the same historical methods as those used by other historians”

The first paragraph initial link is a search “?s=zolondek”, scroll down the listed articles for:

@ https://vridar.org/2018/05/16/testing-the-claim-that-jesus-scholars-use-the-methods-of-other-historians-part-1/

Neil is addressing Michael Zolondek.

Is there a problem I am missing? I linked to the previous posts where I address Zolondesk’s claims and methods: https://vridar.org/?s=zolondek — there are three posts on that page; db has pointed out the relevant one.

In a recent comment above I quoted again Michael’s words where he does say that biblical scholars use the same methods as other historians. I think I have quoted MZ sufficiently comprehensively to cover all he happens to say about how the methods compare. I would like to see him address the words of his I quoted in the comment above.

He objects to my not understanding what he writes but it is he who is overlooking the fact that I have quoted his exact words to support what I have said about his claims. He has not demonstrated to me that anything I have said is a misrepresentation or misunderstanding. I would appreciate it if he would at least posit a response to show me where I have misrepresented him.

The problem that I’ve been trying to lay out is your misunderstanding of the argument and the context of it. I argue that things like considering multiple, independent sources, considering authors’ biases and things that contradict them in their works, considering historical plausibility are all things that ancient historians do. These things have been misconceptualized into “criteria of authenticity.” Historical Jesus scholars who come from that perspective should move closer to the methods and practices of ancient historians more generally. Not really sure how to explain the same thing as I write in the book. If you read the whole chapter again, with an understanding of the context and historical development of Jesus studies, including where we are now, you might understand it more clearly.

Dr Zolondek, I suspect we are talking past each other. I am not addressing your argument per se; rather, I am addressing some methodological assumptions that underlie your argument.

I am addressing what I see as taken-for-granted assumptions behind several of your statements about the methods of certain biblical scholars. And I am attempting to do so fairly without hostility, ridicule or put-down in any way. I am very sure you are sincere, honest, and competent in your field. But from my perspective you are embracing (naturally enough) the methodological assumptions and understandings of many of your peers and supervisors.

I know some of your peers have turned against me with gratuitous hostility but I try not to retaliate. I try to simply present the arguments and the evidence as I find it.

Michael, I know your argument and have cited your words in support of the very points you seem to be saying that I have somehow overlooked. I have a different interpretation and assessment of what you are doing (and the validity of your approach) from what you believe you are doing. Your responses to date do not indicate to me that you understand what my perspective or point of my criticism is.

• It is unlikely that the historical methods used by “other historians” would result in any certainty per the “The Incident in the Temple”:

Zolondek, Michael Vicko (4 January 2014). “We have found the Messiah : the Twelve and the historical Jesus’ Davidic messiahship“. Edinburgh Research Archive. Ph.D. dissertation, The University of Edinburgh, 2013. pp. 178f, n. 672: [now bolded]

See comment by Neil Godfrey [2018-09-23 02:40:56 UTC – 02:40] per “The Jesus Story Mirrors Anthropologist’s Observations of Shamanism?”. Vridar. (20 September 2018).

There is not even a suggestion in my work that NT scholars work by stricter standards. My argument nowhere approaches that. So to say I meant it is entirely erroneous on your part, and I’m here yet again directly telling you that this is not my argument and so you no longer need to say that it is what I “meant” or appeared to argue. Not sure what more is needed. I assume we can agree that I don’t argue that now?

Again, you are simply misunderstanding. My argument is not about historical Jesus scholars generally, nor is it about them using the same methods as ancient historians more broadly. It as an argument about the criteria, how they should be conceptualized, and their value. My point was that we should move away from the form-critical conception of them and get closer to ancient historical methodology, which, yes, uses things like multiple independent sources, ancient authors’ biases in work and things that would appear to contradict them, and historical plausibility.

I am not saying she is without biases. You are not. I am not. No one is without them. I am saying she is widely respected among various fields of scholarship. I am saying you launched an ad hominem against her without ever having spoken to her (I’m presuming you haven’t). I don’t think she does any particular work in Jesus studies, and I believe only secondarily in NT studies. I am not even sure if NT studies is a focus of hers. I don’t know her religious affiliation. To throw doubt on her without knowing anything about her is unprofessional.

Michael, I know your argument is not about historical Jesus scholars generally. Of course it isn’t. You have misunderstood my point and entire approach to such questions generally on this blog.

I am addressing in your work a point I see that is a flawed concept in much (by no means all) biblical scholarship relating to Christian origins. I am comparing the historical methods used by biblical scholars, very often, with those of other historians. (It was in fact biblical scholars who led me to my approach, by the way, in particular Philip R. Davies.)

Michael, I did NOT “launch an ad hominem against” Williams at all. I simply pointed out some points that we can all agree about her background and that should obviously be taken into account when evaluating her reported statement. I have no reason to disrespect or think negatively of Williams in the slightest way at all and I have not done so in my post. Is it “launching an ad hominem against” anyone to point out a potential association that points to the possibility of a certain bias that is relevant to a question under consideration? Of course not.

(It is obvious Williams does not focus professionally on Jesus studies or the NT and your point about such concerns again entirely misses the point I was making. I get the impression you are reading my posts and comments with hostile intent and reading barbs in them that I never imagined making and that are simply not there.)

And again, I know you don’t “suggest” that NT scholars work by stricter standards. And I don’t say you do. I say that that is how I interpret your meaning in effect. Different readers have different interpretations and evaluations and you are objecting to mine without addressing the reasons I have so far given to support my claim.

My point is not about you personally. I wrote about your work because of two reasons: one, it was presented in a way that indicated it was breaking new ground in a certain topic; two, it made some explicit statements about the methods of historians that I believe are implicit in the understanding of historians in many works by NT and historical Jesus scholars.

I believe the assertions that are often made in relation to comparisons of the methods of historians in nonbiblical fields and historical Jesus scholars are misinformed. I have posted often on this criticism and will do so again, including a more detailed reference to your own statements.

You are responding in several places, so I will simply respond here with the central point leading to the confusion. I’m not reading anything of yours with hostile intent. I’m simply stating that you are not understanding my arguments. To date, nothing that you’ve said indicates you have grasped with clarity what I am doing in my discussion of the criteria and methodology. Rather, you keep insisting that I am arguing Jesus scholars are using the same methods as ancient historians more broadly. As long as you continue to hold this view, there is not much discussion that can happen because you are not talking to me, but a fictional version of me you have read into my work. Rather than assuming things in my work, you could simply ask me for clarity.

Regarding Dr. Williams, you put out there, without any discussion with her directly and without any knowledge of her ideology or commitments, the suggestion that one should question the credibility of her comments to me because of what departments she currently works with, namely the school of Divinity, which does not indicate anything about the ideology of anyone there. There are Jews, agnostics, atheists, Christians, and others in that department. That would be considered entirely unprofessional in any respected college or university.

You have not responded to the point I have made about my argument and interest but have inferred in your reply that I am still trying to address “your (though a fictional your) arguments”. You have avoided my explanation entirely. It appears you do not understand the perspective I am coming from.

I am not interested in my posts in you, fictional or otherwise, or your argument about whether Jesus said or did not say he was the Christ, but in your words that I have cited. Refer back to the list of quotations I have taken from your book that explicitly and unambiguously acknowledge that biblical scholars do indeed use tools deployed by other historians. You say other things as well about methods and biblical studies but you make it clear that certain tools are deemed to be used in common by biblical and other historians. That is the point I am addressing. When I address other things you say about methods I make it clear I am addressing other things you also say about methods.

Please refer again to what I actually wrote about Williams and pinpoint exactly how anything I actually said was beyond the bounds of professionalism. It is very clear to me that Williams was reported to have said something that is as misinformed as anything we find among many biblical scholars re historical methods. I was positing a well-meaning explanation for that that did not rob Williams of any sincerity or honesty or aspersions on her reputation in her area of expertise.

I will post further detailed explanations to demonstrate the grounds for my criticisms of methodologies in a future post.

Oh goodness. Let me try this again… What I refer to as “tools” is not the equivalent of methods or saying that Jesus scholars are doing the same thing as ancient historians more broadly. There is no disputing that ancient historians utilize multiple, independent sources when offering historical narratives/reconstructions; that they consider authorial biases and things that contradict them; that they consider accounts’ historical plausibility. These tools developed into some of the criteria of authenticity and the form-critical conception of them. Do you understand my point based on what I’ve just said?

What Williams said was simply what I’ve just stated: that these are the things historians do. Not sure why in response to that you felt the need to question her based on the academic department she works in currently. You disputed her comment on NO other grounds but that. That is absolutely unacceptable in any academic setting.

No disputing? Clearly there is some room for doubt about the same methods being used because you found yourself informing readers that you consulted with a classicist and ancient historian to see if it were indeed true.

You found cause to write repeatedly (and I quoted each instance) and to point out to readers an authority for your claim that biblical scholars used the same tools as other historians.

It is my contention that such claims set up in the minds of readers a false equivalence. They are misleading statements that fall apart under scrutiny and specific examples of comparison and a look at the contexts of some of the statements cherrypicked for quotation. I have posted about this multiple times and will do so again.

You are permitted here to disagree without patronizing.

But let’s not be evasive. I was addressing your citation of Williams as if she was an independent source to support your claim that was expressing some sensitivity over biblical scholarly bias. I was pointing out the misleading way your presented Williams as a source supposedly standing outside of any personal interest in Christian of biblical studies. You wrote:

And I responded

My criticism was the way you suppressed vital information about Williams’s associations that had relevance to the reason you were using her as a source.

You do not appear to think anyone could possibly question what you see as a certain equivalence between biblical studies and other historical inquiries – despite appearing to find it necessary to quote names to buttress your point.

I will do short post explaining why I believe the equivalence you claim is a false one, and how common terms for certain tools in fact mean quite different processes and functions in the two disciplines.

It seems this conversation may be becoming less and less productive. It appears that you are unwilling to go back and read my work within the proper context and with a proper understanding of the historical development of Jesus studies and the criteria of authenticity specifically (and the debate regarding their use and value). Therefore, you simply keep insisting I am arguing things I am explicitly telling you I am not arguing or saying.

Your comments clearly reveal this misunderstanding. For example, my informing readers about the historical development of the criteria of authenticity has nothing to do with there being no dispute about the “tools” ancient historians use. The quotes you use in your post are about how the things ancient historians do were developed and, in my opinion, misused as criteria of authenticity by from-critics and later other Jesus scholars.

Are you disputing that ancient historians do the things I listed? That they do not use multiple, independent sources; consider historical plausibility; etc.? These are the “tools” of which I speak in my discussion on the criteria. My entire point is that Jesus scholars are very often doing history DIFFERENTLY than ancient historians more broadly, and that we should align our methods more closely to our parent field. I am not arguing equivalence, but noting that equivalence is lacking in the form-critical use and conception of the criteria that has persisted. THIS IS EXACTLY THE OPPOSITE OF WHAT YOU ARE CLAIMING I ARGUE.

I am not saying anything with a patronizing attitude. I am actually asking whether you have understand my claims now because, again, you are claiming I am arguing something that I say precisely the opposite of in my book. Not sure how else to get this across.

Noting that Dr. Williams came on board to the school of Divinity because of her expertise is irrelevant to the fact that she noted that ancient historians do the things I mentioned, which no one in the field would dispute. Now, if you want to dispute her claim, or anyone else’s for that matter, you don’t attack her statement based on the fact that she chose a particular academic department. There is really nothing more to say on the point. Any professional in the field will inform you that this is not best practice.

MZ, here is what I wrote:

The part in italics is MY INTERPRETATION of what you are doing and that I will proceed in the follow up post to justify. Do you know how I justify that interpretation?

Are you able to paraphrase what you believe I argued in that and the follow up posts?

Testing the Claim that Jesus Scholars Use the Methods of Other Historians (Part 1)

Part 2 of Testing the Claim that Jesus Scholars Use the Methods of Other Historians

Have you read my discussions so far or only one post (above) that refers back to them?

I am very familiar with academic publishing and citation standards and it there is simply no doubt you suppressed relevant information as I explained above. And trying to twist my comment into some sort of ad hominem attack on Williams is a blatant dys-reading of what I said. Perhaps in the largely faith-based field of apologetics “any professional” will side with you on these points. (I get the clear impression you are not very familiar with more than a tiny handful of books by scholarly historians in nonbiblical studies.)

Sometimes a critical view of a work does not align with the author’s own perceptions and intentions. That’s how critical reviews sometimes work. An author can think the criticism through and engage in a discussion where he or she clearly shows he or she at least understands the criticism, or he or she can otherwise dig in, offended, and retaliate.

NOTE: Unintentionally posted this generally instead of a reply here. Feel free to delete the general post and keep this one.

I actually directly addressed the most relevant points of your original post on that thread. They really haven’t changed. You can go back to that original post of yours and see where you have misunderstood what I’ve said and what I did in that chapter of my book.

Really, this is becoming kind of silly, almost trolling. I’m here telling you to go ahead and ask any clarifying questions that you have, and instead of doing so, you are simply continuing to put forth inaccurate understandings of my work, making disparaging remarks, and referring me to posts I’ve already addressed directly. It seems odd, quite honestly.

There is absolutely nothing I suppressed regarding Dr. Williams. She is widely known and there is nothing unusual about the citation of her. Moreover, and again it’s odd that this has to continue to be stated, the fact that she works with the school of Divinity says absolutely zero about her ideology. There are atheists and agnostics that work in schools of Divinity, NT, OT, and Religion departments.

Neither she, nor I, work in a “faith-based” profession. How anyone can take such a comment seriously is beyond me.

And you can continue with the misrepresentations if you’d like, stating, for example, that I am only familiar with a tiny handful of books on historians outside of biblical studies, but it’s simply unprofessional. I’m right here and you could’ve asked me instead of intentionally attempting to diminish what I’ve done and the works I’ve studied.

Again, please feel free to ask me about my work if you have a genuine and honest interest in understanding what I’m doing in it.

I actually directly addressed the most relevant points of your original post on that thread. They really haven’t changed. You can go back to that original post of yours and see where you have misunderstood what I’ve said and what I did in that chapter of my book.

Really, this is becoming kind of silly, almost trolling. I’m here telling you to go ahead and ask any clarifying questions that you have, and instead of doing so, you are simply continuing to put forth inaccurate understandings of my work, making disparaging remarks, and referring me to posts I’ve already addressed directly. It seems odd, quite honestly.

There is absolutely nothing I suppressed regarding Dr. Williams. She is widely known and there is nothing unusual about the citation of her. Moreover, and again it’s odd that this has to continue to be stated, the fact that she works with the school of Divinity says absolutely zero about her ideology. There are atheists and agnostics that work in schools of Divinity, NT, OT, and Religion departments.

Neither she, nor I, work in a “faith-based” profession. How anyone can take such a comment seriously is beyond me.

And you can continue with the misrepresentations if you’d like, stating, for example, that I am only familiar with a tiny handful of books on historians outside of biblical studies, but it’s simply unprofessional. I’m right here and you could’ve asked me instead of intentionally attempting to diminish what I’ve done and the works I’ve studied.

Again, please feel free to ask me about my work if you have a genuine and honest interest in understanding what I’m doing in it.

I have 2 points for your consideration.

1. On what ground may it be asserted that working at a Divinity School, regardless of one’s personal faith, is not a “faith-based” profession? If there were no Christian faith and no people interested in it, no person, even if a Shinto devoted to the God of Mount Hiei, would have a job at a divinity school. On this ground alone, working at a divinity school must be counted as a faith-based profession. On a related note, Divinity schools were founded by Christians and cater in their scholarship towards those who are deeply interested in Christianity. The majority of people with both a deep interest in Christianity and the finances to support a divinity school (as opposed to, for example, financing other types of scholarship) are Christian. To me, therefore, it seems likely that divinity schools are likely to exert much pressure of various types in order to avoid having their scholars write materials that are overtly antiChristian. A divinity school whose scholars, for example, were to publish books dismissing Jesus as a madman and a violent criminal who deserved to be convicted for something over the violent disturbance in the Temple, or whose books would portray Paul as some combination of insane, incoherent, and a scam artist like Alexander of Abonoteichus, would alienate all Christians and without such supporters and their money, where would the divinity school be? Bankrupt. For this reason, those who work in divinity schools face pressure to, if they must criticize Christianity, to do so softly.

2. For a practical example of a scholar’s involvement in a religiously based institution undermining the scholar’s credibility, it is useful to move beyond divinity schools and Christianity – a good model can help to make everything clear. Consider Edgar Cayce, the alleged psychic, whose ideas maintained (and may still maintain) a following for many years after his death. One of Cayce’s predictions was that in 1968, a portion of Atlantis would rise. In 1968, three people discovered the so-called Bimini Road in the Caribbean. This feature, which has been hailed as a remnant of Atlantis, has been cited as evidence for the accuracy of Cayce’s predictions. Yet people who make these claims tend to ignore the fact that the three people who first discovered the Bimini Road had been, during the course of their exploration of the Caribbean, members of the pro-Caycean Association for Research and Enlightenment. With this fact in mind, the credibility of their exploration efforts decreases. Rather than being seen as dis-interested explorers of the Caribbean who happened to discover evidence that could be interpreted as supporting Edgar Cayce’s claims, they become understandable as people who, starting with an assumption that Cayce’s claims were true, found what they were hoping to find: something that could be interpreted (and was interpreted by them) as a remnant of Atlantis in keeping with Cayce’s predictions. Hypothetically, the three people could have been anti-Cayce zealots who only joined the pro-Caycean Association for Research and Enlightenment in order to debunk Cayce (although evidence suggests that this was not so). However, this is not the first thought that many think when they learn that people who discovered something that could be interpreted as supporting Cayce’s claims belonged to a pro-Cayce organization; rather, they think that the discoverers of the Bimini Road were biased in favor of Cayce during their work that discovered evidence supporting him. The evidence (the Bimini Road) in this case, can be investigated by anyone, but I would, at minimum, want to know whether any investigators were or are associated with the pro-Caycean Association for Research and Enlightenment so that I could investigate them to determine whether they were, rather than being dis-interested researchers, pro-Caycean in their biases. In is true, admittedly, that one does not need to be a member of a pro-Caycean organization to have pro-Caycean bias in one’s research, but membership in such an organization is a strong sign to be wary of such biases. In the same way, being a professor at a divinity school is a sign that a prudent reader would want to have, I should think, in order to investigate whether the person is, rather than being a dis-interested scholar with some knowledge of the Bible, a practicing Christian who may have pro-Christian biases that may distort his or her scholarship about the Bible.

I think you are misunderstanding modern academic programs on religion, some of which are housed in divinity schools. “Faith-based” is a very specific designation, and it is not one that is applied to academic programs. Because an academic program studies a faith or religion doesn’t make it “faith-based.” There are MANY publications that come from religion and theology departments, and NT departments specifically, produced by scholars there that are not embraced by Christians.

You say that: ““Faith-based” is a very specific designation, and it is not one that is applied to academic programs”.

Yet through a Google search I have discovered that there are academic programs that are offered by Christian universities, even reputable ones: see, e.g., “Originally established as a Lutheran Seminary, Luther College is a private liberal arts college in Decorah, Iowa. While the school is affiliated with the Lutheran tradition, it believes that “a rigorous academic program in the context of a faith tradition is the best way for you to discover your life’s meanings and commitments.” The school believes that you do not have to be Lutheran or Christian to receive value from a Lutheran education. If you want to be among some of the top scholars in academia, then you should think about attending Luther College. Luther is one of the top Fulbright producing schools. Along with Biblical Languages, Classics, Philosophy, and Religion, the school offers numerous degree programs. If you are thinking about a specialized career after undergraduate studies, the school offers pre-professional programs like pre-dentistry, pre-law, pre-ministry, and pre-medicine.”

I will acknowledge that non-Lutherans can study at Luther College, but given its strong connection to the Lutheran faith, I would question how likely it would be to hire non-Lutherans or scholars who put little trust in the Bible to teach about the Bible. Much less controversial for a Lutheran College to select scholars who will, in some way, up-hold Lutheran perspectives on the Bible to some degree (such as holding Jesus to be a wise teacher regardless of whatever else he may have been).

But see: I will concede that maybe I have misunderstood modern academic programs on religion. All that having been said, I would think it important to tell a reader that a scholar whom you consult with about the Bible works at a divinity school and name the Divinity school. This would be a useful form of disclosure to the reader for 2 reasons.

1. It would allow the reader to research the divinity school and determine whether it is a divinity school that is biased or unbiased in its approach to religion, either officially (in terms of statements of purpose or statements of faith, etc.) or unofficially (in terms of, for example, choosing as professors only people with certain interpretations of the Bible).

2. Even if the Divinity School were completely unbiased, the mere fact that a scholar works in a divinity school is worthy of note because such a scholar may have more familiarity with Biblical scholarship than a scholar working in another school. When I think of classicists, I think of people whose scholarly focus is not on the Bible and Jewish/Christian writers but on Greco-Roman writers in so-called Paganism – certainly, this was what I studied in Classics as an undergrad.

I understand that this is your perspective. In the academic world, however, and not just biblical studies, there is simply nothing at all unusual about my reference to Dr. Williams. There was nothing suppressed at all.

Many thanks for your polite reply. I am not accusing you of having suppressed anything, but merely saying that you have not not revealed all relevant information about Dr. Williams.