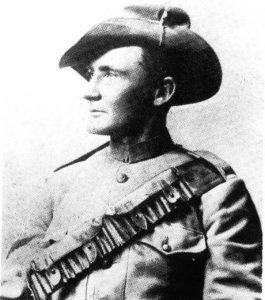

Years ago I walked out of a movie theatre enraged. Thousands throughout Australia at that time did the same. People talked about it for months afterwards, asking “How could they do it!” The “they” were the British colonial masters led by Lord Kitchener; the “it” was the execution of two Australian soldiers as scapegoats to protect the international image of Great Britain. The film was Breaker Morant, based on historical persons and events in the Boer War at the turn of the last century. Morant, nicknamed the Breaker, was a national hero few of us at the time had even heard about. The film revived memories from the early twentieth century that the Breaker was very much a national hero and a sacrificial victim to the British overlords.

Morant has gone not so much into history as into legend. He followed the admired track of other Australian folk-heroes — Ned Kelly, Moondyne Joe, Captain Starlight. They were all men against authority; good bad men or bad good men, always with enough human appeal to disguise the fact that they were outside the law, that they robbed and killed and were brought to book. Behind them all are the near-mythic figures of Hereward the Wake and Robin Hood, of William Tell and the outlaws of the Old West. People prefer to think of them all as bold and brave individuals, self-reliant and strong, defiant against great odds. Morant, in the popular mind, has joined their company.

(Denton in Closed File, cited by Walker, pp. 18f )

Here are the facts about Morant according to Shirley Walker’s article ‘A Man Never Knows His Luck in South Africa’: Some Australian Literary Myths from the Boer War. I list them first so you can begin to wonder how such a figure was able to acquire the status of an Australian mythic hero.

- His name was Edwin Henry Murrant, son of the Master and Matron of the Union Workhouse, Bridgewater, Somerset.

- He lied about his age to marry Daisy O’Dwyer, soon afterwards deserting her and eventually remarrying as a bigamist

- “A young English scapegrace consigned to the colonies for some youthful escapade”

- He had a reputation for defaulting on debts

- A “womanizer”. His nickname Breaker referred to both his breaking in of horses and his breaking of women’s hearts

- A horse thief

- A regular drunkard

- In the Boer War he shot prisoners, including a number who entered his camp under the white flag.

- He also had witnesses to these crimes, including a missionary, murdered.

- On being caught he was tried and executed by firing squad.

There was a positive side:

- He was “well known throughout Australia (i.e. the colonies) as a rough rider, a polo and steeplechase rider”

- a bush poet published in the leading magazine, The Bulletin, under the pen-name “The Breaker”

How does one make a Hereward the Wake or Robin Hood type hero out of raw material like that?

First, one needs the right soil for any seed to germinate. Or, to change the metaphor, one needs a mold by means of which to cast the person to become the hero.

In other words, the ideas of the myth are “out there”, in the minds of an audience who are prepared to love the idea of finding exemplars to fit those ideals. Continue reading “How an executed war criminal became a mythic national hero”