Rene Salm translates from the German:

http://www.mythicistpapers.com/2016/05/27/a-shift-in-time-l-einhorn-book-review-pt-2/

Musings on biblical studies, politics, religion, ethics, human nature, tidbits from science

Rene Salm translates from the German:

http://www.mythicistpapers.com/2016/05/27/a-shift-in-time-l-einhorn-book-review-pt-2/

What life in a cult was like: “We gave away our critical thinking and moral code and surrendered it to him” — Gary Kramer writes about his interviews with former disciples of Buddhafield, including disciple filmmaker of Holy Hell.

Buddhafield espoused starkly different teachings and practices from the Christian cult I belonged to — and both Buddhafield and Christian cults are very different from Islamist political/terrorist “cults” I have spoken about before. The similarities, however, are also very real. I quote from Kramer’s interview those points that also point to my experience and what I have read in the research about terrorist cells.

What led to involvement? Will Allen (WA):

I was on a quest for happiness. I was pretty burned out from college. I liked the teachings I heard, and the people I met, and that was the beginning of the end. I was young and looking for some kind of secret to life—how to live my life and give it purpose.

Another member (David Christopher – DC) replied:

We were looking for something deeper. Our families are a cult. I have a new definition for cult: a group or organization that inhibits your thinking through guilt, shame, or coercion. That can be your family, it can be your church. . . . Most everyone in our community wanted something more—they saw something under the veil and wanted more than just the superficial, and that’s how they entered into this.

You can’t just join the Buddhafield. It’s hard to get in. It’s selective, and secretive. I realized quickly that there was something going on. I wasn’t invited in. There was a process you needed to go through… Eventually you get invited. . . . It was “this is more your family,” and I felt that way—it was way more intimate than my own family.

Why stay?

It’s like any relationship. You find the good and hold on to that as long as you can and overlook all the negatives. . . . (WA)

The craziness wasn’t really apparent for most of us. I’d like to say 80 percent of it is so fricking amazing that you can live in this state of bliss. And 20 percent was a little weird but you say, “I’m not going to look at that part.” (DC)

Comment on the culture, the rules: Continue reading “Holy Hell: What life in a cult was like”

Golden Dawn party attempts to shut down Mythicism Conference

A translation of part of the letter by Golden Dawn to the Mayor of Athens:

The Greek Constitution stated that the Orthodox Christian Faith is the dominant religion of our homeland. How can the ministry protect protect the holies of 2000 years of our homeland, if it does not intervene and allows the conference to take place, which is potentially heretical and aims to destroy the faith of Greeks?

A landmark in national life has just been passed. For the first time in recorded history, those declaring themselves to have no religion have exceeded the number of Christians in Britain. Some 44 per cent of us regard ourselves as Christian, 8 per cent follow another religion and 48 per cent follow none. . . . We can more accurately be described now as a secular nation with fading Christian institutions. . . . .

Christians, for their part, should not automatically associate a decline in religiosity with a rise in immorality. On the contrary, Britons are midway through an extraordinary period of social repair: a decline in teenage pregnancies, divorce and drug abuse, and a rise in civic-mindedness.

That’s from a leading article in the 28th May 2016 edition of The Spectator: Britain really is ceasing to be a Christian country.

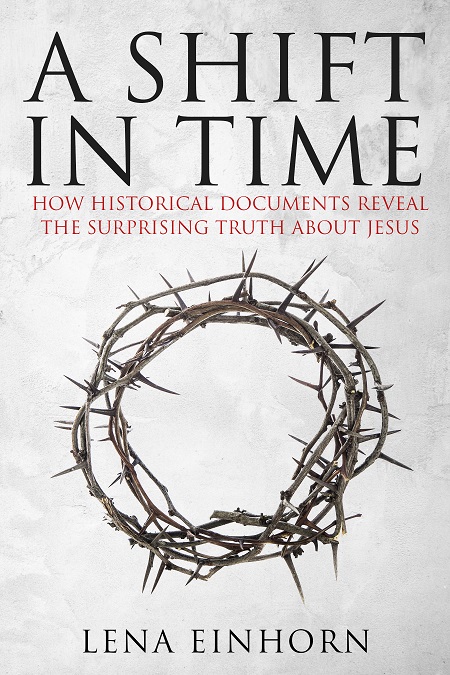

Once more exploring a question raised by Lena Einhorn in A Shift in Time — this time with doubts….

Was Jesus originally the Egyptian prophet we read about in the works of the ancient Jewish historian Josephus? Lena Einhorn seems to think so in A Shift in Time where she lists seven points in common between them. I won’t discuss those seven points but will look at her seventh:

And last, but not least, “the Egyptian” is defeated on the Mount of Olives, which is where Jesus was arrested. It is also from there that both men have declared their prophecies [that the walls of Jerusalem would fall down].

Actually Jesus predicted the walls of the buildings, in particular the Temple, would be pulled down, not the walls of Jerusalem. I have thought of the Egyptian as attempting to re-enact Joshua’s feat of miraculously having the walls of a great city collapse while Jesus (the Greek form of Joshua) spoke of the destruction of the Temple. But that’s a caveat we’ll set aside for now but return to later.

To begin, let’s be sure we have the picture. Josephus writes about the Egyptian twice, first in Wars (written about 78 CE) and second in Antiquities (about 94 CE). Here’s what he tells us:

But there was an Egyptian false prophet that did the Jews more mischief than the former; for he was a sorcerer, and pretended to be a prophet also, and got together thirty thousand men that were deluded by him;

these he led round about from the wilderness to the mount which was called the Mount of Olives, and was ready to break into Jerusalem by force from that place; and if he could but once conquer the Roman garrison and the people, he intended to domineer over them by the assistance of those guards of his that were to break into the city with him.

But Felix prevented his attempt, and met him with his Roman soldiers, while all the people assisted him in his attack upon them, insomuch that when it came to a battle, the Egyptian ran away, with a few others, while the greatest part of those that were with him were either destroyed or taken alive; but the rest of the multitude were dispersed every one to their own homes, and there concealed themselves.

War of the Jews 2.261–263

Then about fifteen years later Josephus wrote:

There came out of Egypt about this time to Jerusalem one that said he was a prophet, and advised the multitude of the common people to go along with him to the Mount of Olives, as it was called, which lay over against the city, and at the distance of five furlongs.

He said further, that he would show them from hence how, at his command, the walls of Jerusalem would fall down; and he promised them that he would procure them an entrance into the city through those walls, when they were fallen down.

Now when Felix was informed of these things, he ordered his soldiers to take their weapons, and came against them with a great number of horsemen and footmen from Jerusalem, and attacked the Egyptian and the people that were with him. He also slew four hundred of them, and took two hundred alive.

But the Egyptian himself escaped out of the fight, but did not appear any more.

Antiquities of the Jews 20.169–172

The story has changed in some details over those fifteen years. The event itself is set in the 50s CE. Josephus first writes about it around 20 or more years later. That’s about the same time span between today and the catastrophic raid on the Branch Davidian cult in Waco, Texas. Josephus appears to be saying that the Egyptian’s plan was to attack Jerusalem without any thought of a miracle to open the gates for them.

Approximately thirty five years after the event (compare today’s distance from the assassination attempt on President Reagan) Josephus introduces the Egyptian’s prophecy to command the walls of Jerusalem to do a Jericho.

So unless I am missing something hidden by a poor translation it seems that there is room for doubt that the Egyptian really was known at the time to have told his followers that the walls would obey his voice. One can imagine people talking about this fellow and mockingly asking how he could possibly have seriously thought he would take over Roman occupied Jerusalem, and how from such scoffing someone suggests he probably thought he could repeat the Jericho miracle. Or maybe he really did make such a declaration and Josephus simply failed to mention it in his first account. However that may be, years later when the event was recalled this detail did become part of the story. Who knows if it was Josephus’s memory or if he picked up the detail from someone else?

What, then, connects the Mount of Olives setting in the story of the Egyptian with our accounts of Jesus?

There are two links. Continue reading “Jesus and “The Egyptian”: What to make of the Mount of Olives parallel?”

ISIS just delivered its ‘weakest message’ ever by Pamela Engel (Business Insider Australia, h/t IntelWire)

Indeed, we do not wage jihad to defend a land, nor to liberate it, or to control it. . . .

We do not fight for authority or transient, shabby positions, nor for the rubble of a lowly, vanishing world. … If we were able to avert a single fighter from fighting us, we would do so, saving ourselves the trouble. However, our Quran requires us to fight the entire world, without exception. . . .

Do you, oh America, consider defeat to be the loss of a city or the loss of land? Were we defeated when we lost the cities in Iraq and were in the desert without any city or land? And would we be defeated and you be victorious if you were to take Mosul or Sirte or Raqqah or even take all the cities and we were to return to our initial condition? Certainly not!

ISIS is on the ropes. They once propagated a message and aura of invincibility and recruits came to them from around the world. That’s all in reverse now.

Unfortunately other news has pointed to Al Qaeda and its “partner” Al-Nusra re-emerging in Syria (Al Qaeda About to Establish Emirate in Northern Syria and Al Qaeda Blessing for Syrian Branch to Form Own Islamic State). I have almost completed Vanguard of the Imam: Religion, Politics, and Iran’s Revolutionary Guards by Afshon Ostovar. Ostovar has answered a question I had about the exact nature of Iran’s involvement in Syria. Just as an Islamist militia has been built throughout Iran to violently cower dissidents and to be prepared to wage asymmetric warfare against a future invasion, so Iranian trainers have been training Syrians by the thousands to replicate the same type of organized gangs in Syria. Syria is the most depressing news.

Christianity may teach us to be honest but as long as dishonesty serves the interests of faith I’m sure God forgives.

A certain Butler University Professor (his blog makes it clear he writes in his capacity as a Butler academic) who is well known for his strident dogmatism on the question of the historicity of Jesus has been at it again.

He writes in response to a “meme” that he realizes is false or flat wrong in every way except one: it scorns mythicism!

First falsehood:

the attempt to argue that because someone is only mentioned in the New Testament, therefore they are not historical, simply does not work.

Of course he cites no instance of anyone arguing this way. No publication putting in a word for the mythicist case that I know of has ever suggested that “because someone is only mentioned in the New Testament, therefore they are not historical”.

But he does say something that is obviously true. I think we can all agree with the following:

Mythicist dogmatists and Christian fundamentalists are not at polar opposite ends of the spectrum, except on the trite matter of what they insist they know. Their approach is an all-or-nothing one that are mirror images of one another, two sides of the same coin.

There certainly are “mythicist dogmatists” who are as, well, dogmatic, as any Christian fundamentalist.

Then he writes something most professional:

Historians, on the other hand, are supposed to deal in a nuanced manner with evidence, and to recognize that each piece of evidence must be assessed separately and on its own terms.

But then he slips off the rails. Two true statements bracketed by two false ones. A nice chiastic structure.

And so the heart of the matter is this: mythicism – the complete dismissal of the historicity not just of accounts but of the individual portrayed in them – is as illogical and indefensible as claims of Biblical inerrancy – the complete acceptance of the historicity of everything in the Bible because the existence of individuals mentioned in it has been confirmed.

Notice where he slipped? At first he made the obvious statement that a “mythicist dogmatist” is as bad as a “Christian fundamentalist”, but here he speaks of “mythicism” generically. Mythicism itself is as bad as Christian fundamentalism. I would have thought “mythicism” would stand in this context as a counter to “Christianity”: just as Christianity has its fundamentalists so does mythicism have its dogmatists. Both stand outside the realm of serious discussion.

And then he underscores the point:

Neither mythicism nor Christian fundamentalism is engaged in the practice of history.

Not, “neither mythist dogmatism nor Christian fundamentalism”, nor, of course, “Neither mythicism nor Christianity….”

Then we meet the professional indignation:

And when historians and scholars object to this misuse of their work, mythicists and inerrantists typically respond in the same way: by insisting that the academy is in fact conspiring to cover up the truth or infested with an ideology that blinds us to the truth.

Interesting that he speaks of “historians and scholars”. Is he trying to impress readers once again that theologians like himself really are true historians and scholars? Certainly a good number of theologians do call themselves historians and in one sense they are, but even in their own ranks we find criticisms that their approach to history is quite different from the way other historians work. (Raphael Lataster demonstrated that most emphatically in his book. Recall a paper of his discussing historical Jesus methodology that was rejected by a scholarly Biblical publisher was accepted by a Historical conference.) And of course our Butler Professor cannot be ignorant of the fact that it is theologians themselves, his own peers, who regularly complain about the ideology that blinds them as a whole to seriously radical ideas.

Recall again his point:

Historians, on the other hand, are supposed to deal in a nuanced manner with evidence, and to recognize that each piece of evidence must be assessed separately and on its own terms.

Do I need to quote again here the many instances of nuance and tentativeness and scholarly humility in the way scholarly mythicists (scholarly referring to any mythicist who argues in a scholarly manner — leaving aside the dogmatists) very often present their arguments and set them beside a list the many abusive and dogmatic denunciations of theologian “historians and scholars” like the Butler Professor himself when arguing for the historicity of Jesus?

Another illustration of the only way a devoted member of a “tribe” — whether religious cult or ISIS — can begin to loosen their attachment and head towards the Exit door appeared in AP’s The Big Story: Islamic State’s lasting grip is a new hurdle for Europe, US written by Lori Hinnant. Its message is consistent with my own experience or exiting a religious cult and with the scholarly research I have since read on both religious cults and terrorist groups, both Islamist and secular.

Lori Hinnant is discussing the experiences of a French program to “de-radicalise” former ISIS members. Its key sentence:

Only once doubts are seeded can young wouldbe jihadis themselves reason their way back to their former selves.

Attempting to argue them out with reason is futile. In the case of fundamentalist cults we can easily enough see why: their thinking is entirely circular. There is no escaping. All “contrary thoughts” are from Satan and to be cast down, writes Paul in 2 Corinthians 10:5. It is no different with Islamic extremists, as previous posts have illustrated. Membership of the group is the foundation of the identity of each member; the group is their family and the bond stimulates the dopamine. Life only has meaning as an active member of the group.

Try talking anyone out of leaving their family and walking away from the cause that gives their life meaning.

There is no reasoning with someone in the thrall of a jihadi group, those who run the program say, so the recruits have to experience tangible doubts about the jihadi promises they once believed. Bouzar said that can mean countering a message of antimaterialism by showing them the videos of fighters lounging in fancy villas or sporting watches with an Islamic State logo. Or finding someone who has returned from Syria to explain that instead of offering humanitarian aid, the extremists are taking over entire villages, sometimes lacing them with explosives. Only once doubts are seeded can young wouldbe jihadis themselves reason their way back to their former selves, she said.

That’s how it’s done. It won’t happen immediately. At first the response to “proofs” of hypocrisy among the group’s leaders and deception in what they promise will be met with incredulity, a suspicion that the stories are all lies. But show enough with the clear evidence that the stories are not fabrications and slivers of doubts have a chance of seeping in. Some will react with even more committed idealism, convincing themselves that they will fight the corruption within. But their powerlessness will eventually become apparent even to themselves.

Only then will the member begin to “reason their [own] way back to their former selves”.

In my previous post I said I was wanting to explore in depth some of Lena Einhorn’s observations. One that I consider most striking concerns the climactic crucifixion itself. We are so used to hearing that crucifixion was a very common method of execution for rebels in Roman times that we don’t pause to ask questions when we read about Pilate’s crucifixion of Jesus along with two “thieves” or “robbers” (translated “bandits” in the NRSV):

Mark 15:27 — And with him they crucified two bandits [λῃστάς – lestes], one on his right and one on his left.

Matthew 27:38 — Then two bandits [λῃσταί – lestai] were crucified with him, one on his right and one on his left.

In the Gospel of John we find Barabbas, the one freed in exchange for Jesus, described the same way:

John 18:40 — They shouted in reply, “Not this man, but Barabbas!” Now Barabbas was a bandit [λῃστής – lestes].

Now λῃστής (lestes) is the Greek word for “robber”, but the historian who has left us an account of the Jewish War with Rome and the many decades prior to that event, Josephus, uses λῃσταί (the plural of λῃστής) to describe anti-Roman Jewish rebels. Josephus was writing around the same period that many scholars believe the evangelists were composing the our canonical gospels.

The gospel use of “lestai/rebels” to describe Barabbas and the two who were crucified with Jesus is not new. It is found in the scholarly literature readily enough.

Einhorn takes the next step and examines the times Josephus tells us the lestai were active. I have summed up Einhorn’s observations in the following table.

|

Accounts of “lestai” activity by Josephus |

||

| 63-37 BCE | 15 times | Beginning of Roman occupation |

| 37-4 BCE | 22 times | |

| 4 BCE – 6 CE | 6 times | Crushing of Census revolt |

| 6-44 CE | No references of lestai activity | Time of Jesus |

| 44-48 CE | 2 times | Return of direct Roman rule after death of Agrippa I |

| 48-59 CE | 20 times | |

| 59-66 CE | 21 times | Lead up to the war with Rome, 66-70/73 CE |

There is an exception that Einhorn points out:

The only hint about activity during Jesus’s time is a sentence in War, saying that “Eleazar the arch-robber,” active in the 50s, together with his associates “had ravaged the country for twenty years together.” In Antiquities, however, it only says that Eleazar “had many years made his abode in the mountains.” (A Shift In Time, p. 45)

At this point I am reminded of my earlier posts, Did Josephus Fabricate the Origins of the Jewish Rebellion Against Rome? and Josephus Scapegoats Judas the Galilean for the War?. In those posts we saw reasons to think that Josephus in Antiquities was compelled to revise certain aspects of his earlier account (War), presumably under pressure from other Jews in Rome who took umbrage at his earlier portrayals of other parties involved. Recall Josephus himself was a less than admirable self-serving traitor. If so, when thinking about Einhorn’s comparison in the quotation above we have a little more reason to give more weight to the Antiquities reference.

None of this data proves there was no “lestai” activity in the time of Jesus, but compare this datum with other general background information. Continue reading “Another Lena Einhorn Observation — Anachronistic Crucifixions in the Gospels”

I recently completed reading A Shift in Time: How Historical Documents Reveal the Surprising Truth About Jesus by Lena Einhorn.

I recently completed reading A Shift in Time: How Historical Documents Reveal the Surprising Truth About Jesus by Lena Einhorn.

Lena Einhorn proposes a radical rethink of Christian origins and does so in a welcome methodical and understated manner. Far from being a sensationalist weaving of data into a mesmerizing filigree of yet another conspiracy or gnostic theory, Einhorn lays out clearly and concisely the evidence that she believes has been overlooked and on the whole leaves it to readers to draw their own conclusions, keeping her own conclusions largely in the background. By the time I had finished the book I found myself thinking that if there is evidence for the Jesus of the gospels being based on a historical person it could well emerge through an argument like Einhorn’s. While I am not ready to embrace her own conclusions (I think much more data needs to be thrown into the mix for a full explanation) her book nonetheless raises very interesting questions.

The dust jacket blurb includes the line by Professor Philip R. Davies, “this book should make us think.” And it does.

Anyone familiar with the Gospels and Acts who has out of curiosity also read Josephus has surely been struck by periodic reminders of what we find in the New Testament narratives and thought, “Interesting, but of course it can be nothing more than coincidence because the Jesus story happened much earlier.” By taking these “coincidental” allusions and analysing them more systematically in comparison with the Gospels and Acts, Einhorn asks us to think through their implications and address new questions.

Einhorn’s thesis is that many allusions and apparent anomalies in the Gospels and Acts coincide with and find historical setting in the events and personalities in the two decades leading up to the Jewish War with Rome. That is, about twenty years after the New Testament historical setting of the Jesus narrative. Sometimes further support for this “shift in time” comes from other sources (both Christian and Jewish) outside the writings of Josephus.

Einhorn has a gift for presenting complex data in a clear and comprehensible way for anyone not familiar with the history of the various regions around Syria-Palestine in the first century, or with the fundamentals of historical Jesus scholarship. Her frequent bar chart and table illustrations assist the reader in keeping track of the multiple parallels between the history found in Josephus and the Gospel-Acts accounts and their respective chronologies. Each brief chapter expounds a single thematic parallel.

An example of the parallels discussed: In the Gospels-Acts narrative we find reference to the death of Theudas preceding the death of Jesus; allusions to activity of rebel-bandits and the crucifixions of them; a hostile Galilean-Samaritan rift; an attack on an otherwise unknown Stephen that precipitates a new wave of widespread violence; two contemporaneous high priests, conflict between the Roman procurator and a Jewish king; a Roman slaughter of Galileans; a visit of a messianic figure to the Mount of Olives just prior to the violent dispersal of his following . . . . None of these phenomena are testified beyond the New Testament to have been found in the time of Jesus and early Church (around the year 30 CE), yet curiously all are found recorded by Josephus about twenty years later. As one who has also tried to draw attention to the absence of evidence for popular messianic fervor in early first century Judea I found Einhorn’s observations very attractive.

Are the parallels “real”? Einhorn herself raises this question several times but has enough respect for readers to allow them to decide. She is content to point out the unusual concentration of them within a narrow time frame and it is this detail that cries out for an explanation. We know coincidences do happen, sometimes quite complex ones. Recall the parallels between the Lincoln and Kennedy assassinations even allowing for some exaggeration and invalid data. We do have a natural tendency to find patterns “even where none exist”. At the same time scholars studying the Gospels in relation to the wider literature of the day (e.g. Dale Allison Jr, Andrew Clark, Dennis MacDonald, Thomas Brodie are just a few examples whose work has been discussed on this blog) have established criteria for identifying “real parallels”. Two criteria that regularly appear in such lists are the density of the parallels and their ability to generate new understanding of how and why the text may have come about. This is where the strength of the parallels in Einhorn’s thesis lies.

Ireneo Funes, the eponymous character in Jorge Luis Borges’ short story, “Funes, the Memorious,” lived the first part of his life completely in the moment. Recalling his first encounter with the enigmatic figure, the narrator relates an incident from long ago when he and his cousin Bernardo were racing on horseback, trying to outrun a storm. They heard, suddenly, the sound of footsteps on the brick footpath above. It was Funes.

Bernardo unexpectedly yelled to him: “What’s the time, Ireneo?” Without looking up, without stopping, Ireneo replied: “In ten minutes it will be eight o’clock, child Bernardo Juan Francisco.” The voice was sharp, mocking. (Borges, 1967, p. 36)

In those days, Funes always knew the exact time; he knew about now, but remembered nothing of the past. Later, when the narrator meets Funes, he explains how an accident changed everything.

For nineteen years, he said, he had lived like a person in a dream: he looked without seeing, heard without hearing, forgot everything — almost everything. On falling from the horse, he lost consciousness; when he recovered it, the present was almost intolerable it was so rich and bright; the same was true of the most ancient and most trivial memories. (Borges, 1967, p. 40)

The fall left Funes unable to walk, and that paralysis becomes a metaphor for the crushing weight of all remembrances, which immobilize and suffocate. For while he can remember everything, his mind is inundated with every detail about every moment that he has ever experienced — and not only the event itself, but the clear recollection of each time he has recalled that event. Continue reading “The Memory Mavens, Part 10: Memory and History (1)”

Alternet has published an interview with the author of a book I have recently twice posted about:

My related posts:

A few excerpts from the interview . . . . First, on evolutionary psychology itself:

Robin Lindley: . . . . What did you learn from neuroscientists and others about why our brain tends to work this way?

Rick Shenkman: Whatever you make of Evolutionary Psychology, and many people hold it in dim regard, its main assumption seems very compelling to me and that is that our brain evolved to address the problems we faced during the Pleistocene, a two and a half million long period. See a leopard in the jungle and you jump. That’s your automatic brain at work. Your instincts. You don’t have to think about jumping, you just do. We jump out of the way because people who jumped when danger approached were more likely to survive and pass along their genes than those who didn’t.

A scientific consensus now exists that the brain works by using either System 1 or 2, as Daniel Kahneman explains in his book, Thinking Fast and Slow. System 1 is automatic thinking, System 2 is reflective. I found this fascinating. It helped explain how we respond to politics. Eventually, I came to the conclusion that we respond to politics most of the time using System 1. This insight wasn’t my own. I first encountered it watching a video lecture by the Cornell social scientist David Pizarro. It made a deep impression. Fortunately, I came across it early on in my research.

We are more Mulder than Scully . . . despite the strongest wishes of us sceptics that it be otherwise.

Robin Lindley: Our trust in leaders is often misplaced. You’re an expert in presidential history and you recount numerous examples of when presidents lied but there was little public reaction, such as when Grover “Jumbo” Cleveland failed to disclose he had cancer and Lyndon Johnson lied about the Gulf of Tonkin incident and Richard Nixon lied about Watergate. The public response was muted and you attribute that response to an innate credulity. How do you explain that?

Rick Shenkman: Human beings are basically believers as Harvard’s Daniel Gilbert has demonstrated. To borrow a line from another social psychologist, we’re more like Mulder than Sculley from the “X Files.” The reason is fairly straightforward. We couldn’t accomplish much if we went around skeptical of everything. Once we decide on a matter we are inclined to consider it settled unless a good reason comes along to make us question it. That gives our brain a chance to focus on threats and opportunities around us. Experiments with sea slugs that I cite in the book show this is a feature of the animal brain. It has to do with our habituation to information. Once we become accustomed to something we stop thinking about it. We grow bored by it. That’s our brain helping us keep focus on what’s new. It’s a survival instinct and it shows up, as I say, even in snails, as the scientist Eric Kandel proved half a century ago.

Another factor comes into play. We want to believe in our leaders. So it takes us quite a bit of time to become convinced that they aren’t all they’re cracked up to be. And once we cast a vote in favor of a leader we tend to come to their defense when attacked. That’s our partisan brain at work. We like being consistent. So if we decided that someone is a good leader we tend to dismiss any evidence to the contrary. Our brain literally shuts off the flow of electricity to neurons telling us something we don’t want to hear that might make us doubt our beliefs.

There are other factors, to be sure. I spend several chapters addressing these.

Neil’s post from last year — “Why Does Jesus Never Do Anything Wrong?” — got me thinking about a story told by David Livermore in his course, Customs of the World: Using Cultural Intelligence to Adapt, Wherever You Are. He tells of a New Testament scholar and minister who performed a small experiment in which he asked people of different cultures to tell him the parable of the Prodigal Son. Afterward, he compared the points of story to what people remembered, noting what they tended to remember as well as what they left out.

His results were somewhat surprising. It turns out that our cultural background, social context, and personal history can have a large impact on what we consider important. Without realizing it, our frame of reference profoundly distorts how we understand and recall information.

Although Livermore and others have used this anecdote (you can find many references on the web), I found it rather difficult to track down the original scholarship. Sadly, the book in which the paper first appeared, Literary Encounters with the Reign of God, is far too expensive for me; however, you can see bits of it in the Google Books preview. Fortunately, the author, Mark Allen Powell, recapitulates much of his paper in the book, What Do They Hear? Bridging the Gap Between Pulpit and Pew.

Powell, a narrative critic, frequently uses the term polyvalence, which for him has a specific meaning:

Simply put, polyvalence refers to the capacity—or, perhaps, the inevitable tendency— for texts to mean different things to different people. Literary critics differ drastically in their evaluation of polyvalence (i.e., friend or foe?), but virtually all literary critics now recognize the reality of this phenomenon: texts do mean different things to different people and at least some of the interpretive differences that have been examined (e.g., gender-biased interpretations) appear to follow fairly predictable patterns. (Powell, 2007, p. 12)

I would add that the situation might even be worse for those of us who were steeped in a particular tradition since childhood. Not only have I been hearing New Testament stories for over five decades, but I’ve been told what they mean, again and again. I even know them by titles that drive the reader or hearer to understand them from an orthodox point of view. For example, I knew the parable of the Prodigal Son long before I knew what the word “prodigal” even meant.

As I said earlier, Powell asked a number students to pair off, then read, and finally describe the parable to their partners. He then noted the details they emphasized or omitted. (The exercise comes from Rhoads, Dewey, and Michie’s Mark as Story.) Oddly enough, they all left out the part about the famine that struck right when the young man’s money ran out. Powell notes: Continue reading “The Prodigal Son: Cultural Reception History and the New Testament”