A former jihadist is interviewed for his views on the question “What makes vulnerable young Muslims prone to being recruited by groups like the Islamic State?”

It seems a silly question to many. After all, they’re Muslims. They believe in a holy book that commands them to kill, kill, kill. What else is there to know? If a specialist scholar in Islamic studies and advisor to government anti-extremist programs fails to mention the word “religion” when summing up the essential radicalisation process in a Time article then many will dismiss his words as an apologetic whitewash. If innumerable Muslims are themselves the victims of Islamic terrorism (with death tolls higher than Westerners by orders of magnitude) it seems to make no difference to the determination to insist that it is the Muslim religion itself (whatever that is) that is to blame!

Well this article was an interview with a former jihadist, not an ivory tower egg-head.

For those interested in garnering a wide expanse of data from which to prepare a hypothesis on the reasons for radicalisation I point to We Spoke to a Former Jihadist About How Young People Become Radicalized. Others can ignore this post, return to an Islamophobic [I use the term of those who express a phobia of anything Islamic] or other hate site for reassurance that their viscera are on the right cerebral track, and perhaps return to share their convictions and denounce whatever is expressed here. Others interested in genuine dialogue, questions and alternative suggestions are most welcome.

The question asked was this:

What makes vulnerable young Muslims prone to being recruited by groups like the Islamic State?

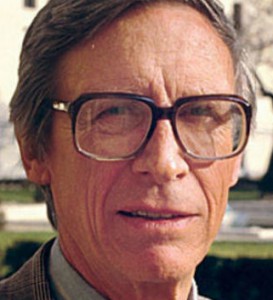

The interviewee was Mubin Shaikh. Who is Mubin? . . . .

Born in Toronto and raised Muslim, Mubin Shaikh became a radical Islamist after a trip to Pakistan in the 1990s. Back in Canada, Shaikh recruited other young Muslims for the cause of jihad. But 9/11 led him to question his path. After a stint in Syria studying the Quran, he returned home changed once again, this time determined to fight the militarism he had espoused. Working with CSIS, Shaikh was a government agent in the “Toronto 18” case, where a group of mostly young Muslims were convicted of plotting to attack Canadian institutions. Today, Shaikh campaigns against Islamophobia while also trying to stop radicalization in his own community, using social media to engage directly with Islamic State sympathizers. And while he still works with Western governments, he’s not afraid to criticize Western policies that he says fuel the radicalization he fights.

And here is Mubin’s answer to that opening question:

You’re dealing with a social movement. It’s beyond a terrorist group. And social movements have grievance narratives. The reason why those grievance narratives resonate is because they are based in fact. It might not be complete fact and it might be their way of interpreting world events, but the reality is that when they say that their grievance is about Western foreign policy, particularly the bombing of Muslim countries—they’re not wrong when they say that.

When I was around in 1995, we would watch videotapes [of jihadist propaganda], and then [DVDs] came out and we watched DVDs. But what modern day social networking has done is it’s accelerated that exponentially. You’re sitting there at a television screen or computer screen, you’re watching these images over and over and over—it’s traumatizing you. Your eyes will be overwhelmed with visual images of death, destruction, killing, torture, oppression [of Muslims].

The psychological term is “vicarious deprivation.” So now, I’m not deprived myself individually, but I’m watching these videos about my people being oppressed and suddenly their deprivation and their oppression becomes my deprivation and my oppression, and enter that extremist message, “OK, you see that now? You feel that now? What are you going to do about it?”

Following questions:

And what are the social conditions that young Muslims live in that make them susceptible to that?

You’re involved right now in efforts to stop Muslims from being radicalized, how do you go about that? What do you tell them and what do they tell you?

But you have the Islamic State themselves and also [critics of Islam] like the New Atheists, quoting passages like Chapter 9, Verse 5 saying, “Kill all the non-believers.”

I won’t take the time to discuss. It appears this discussion is more about polarisation than it is about mutual learning. There are several additional follow-up questions, too. (Only) For those interested.

Like this:

Like Loading...